Portopulmonary hypertension

The prevalence of PAH may be as high as 5% in people with advanced liver disease awaiting transplantation,9 and may be related to their high cardiac output state or to the presence of toxins that are not eliminated.

Symptomatic patients and transplant candidates should undergo echocardiographic screening for pulmonary hypertension; cardiac catheterisation is needed in cases with raised systolic PAP in order to obtain a clear diagnostic picture. In those with severe pulmonary hypertension, liver transplantation is contra-indicated though anecdotal evidence suggests that pre-treating these patients with disease-targeted therapy may improve the outcomes post liver transplantation.

Patients with POPH have been excluded from most randomised trials. Treatment with disease-targeted therapies for POPH is based on anecdotal evidence. Although ERAs may be hepatotoxic, they may be considered in Child class I and II, particularly the newer ERAs such as ambrisentan and macitentan which have a lower risk of drug-associated liver toxicity Despite these limitations, the treatment algorithm discussed in Module 3 should be applied to patients with PAH associated with portal hypertension.

Learning points

- Treatment of portopulmonary hypertension lacks a satisfactory evidence base

- Hepatotoxicity of some agents limits treatment options

Pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with HIV

Pulmonary arterial hypertension is one of the long-term complications of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and is seen in about 0.5% of infected individuals.10 This figure is in effect unchanged despite the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Duration of HIV infection is a risk factor for the development of PAH but CD4 count is not. Since viral particles are not found in the pulmonary endothelium, HIV infection is proposed to have an indirect action through inflammation, growth factors or endothelin.

Routine screening for PAH is not recommended for HIV patients but echocardiography is indicated in patients with unexplained dyspnoea. Right heart catheterisation will confirm the diagnosis and exclude left heart disease.

The evidence base for treatment of patients with HIV and PAH is limited since such patients have been excluded from most trials. Anticoagulation is not routine because of the increased bleeding risk observed in these patients and since drug interactions may occur. These patients appear to be non-responders in vasoreactivity testing. Iloprost has been shown to improve 6MWT and NYHA classification.11 However, the same treatment algorithm used for patients with PAH should be considered.

Learning points

- HIV-related PH is a rare form of the disease

- Echocardiography is recommended in HIV patients with breathlessness

Thromboembolic disease

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is important because the majority of patients will be suitable for pulmonary endarterectomy surgery (see figure 1). This surgery carries a mortality of at least 5% in experienced centres in selected patients. Patients who survive to three months have an excellent outlook for the future.

CTEPH may well be underdiagnosed: a recent study in patients with acute pulmonary embolism (PE) showed an incidence of CTEPH as high as 3% after one year and 4% after two years.12 Further, acute PE may be clinically silent and CTEPH may develop in the absence of a history of previous PE. The median ages at diagnosis is 63 years with both genders being equally affected.

Risk factors for development of CTEPH include splenectomy and chronic inflammatory bowel disease. The differential diagnosis includes pulmonary arterial sarcoma, tumour cell embolism, parasites, foreign body embolism and congenital or acquired PA stenosis.

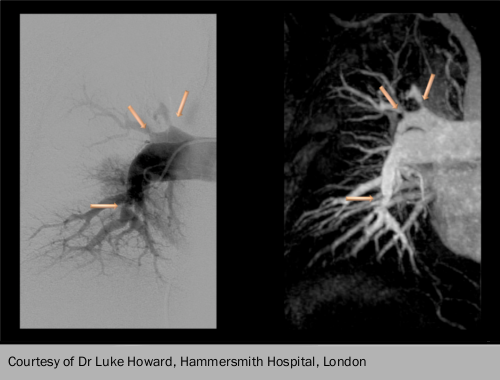

CTEPH should be considered in patients with unexplained pulmonary hypertension, especially those with a history of venous thromboembolism or acute PE. The ventilation/perfusion lung scan is the screening method of choice because it has higher sensitivity than CT scanning: a normal ventilation/perfusion scan effectively excludes CTEPH. If CTEPH is considered possible, the patient should be referred to a PH/CTEPH expert centre for further investigation. This includes CT pulmonary angiography and right heart catheterisation plus or minus pulmonary angiopgraphy. MRI of the pulmonary circulation and selective angiography are needed for surgical assessment (see figure 2). It is also important to note that the diagnosis of CTEPH can be made after at least three months of effective anticoagulation, in order to differentiate CTEPH from ‘subacute’ PE.

Once the diagnosis is made, patients are assessed for operability. If they are and the risk/benefit ratio is considered acceptable, pulmonary endarterectomy is the treatment of choice, with lifelong anticoagulation and targeted medical therapy if symptomatic PH continues post-operatively. For those with non-operable CTEPH, targeted medical therapy plus or minus balloon pulmonary angioplasty are the current options. Ultimately, for those with severe persistent symptomatic PH, lung transplantation must also be considered.

After effective surgery, most patients have an immediate and significant decrease of pulmonary arterial pressure, an increase in cardiac index and improved gas exchange. Maximum benefits of surgery may take six months or more to emerge. Long-term results with respect to survival, functional class and right ventricular function are favourable for most.13

Recently, riociguat was shown to increase 6MWD in those with inoperable CTEPH or persistant post-operative PH and is now recommended. Pregnancy may be considered after successful pulmonary endarterectomy.

Learning point

- Lifelong anticoagulation is warranted in patients with CTEPH

- Riociguat is now approved in patients with inoperable CTEPH or those with persistent/recurrent CTEPH after PEA

- Screening for CTEPH in asymptomatic survivors of PE is not recommended

Pulmonary hypertension due to left heart disease

Pulmonary hypertension is a common complication of left heart disease. It develops due to post capillary increase in filling pressures. However, this can trigger vascular remodelling leading to a further increase in mPAP, in excess of of the PCWP rise. While the term ‘out of proportion’ PH has been used in the past, this is no longer recommended. For consistency, a combination of diastolic pressure gradient and PVR should be used to define the different types of left heart disease associated pulmonary hypertension. Diagnosis should be made preferably by elective RHC in a volume optimised patient.

The underlying disorder and any concomitant diseases such as sleep apnoea should be treated. While there have been small trials using PAH therapies in these patients, they have been small and had a number of methodological limitations. Hence, the use of PAH-approved therapies is not recommended in PH-LHD.