Atrial fibrillation (AF) increases stroke risk fivefold. Oral anticoagulation (OAC) with warfarin reduces the risk of stroke by 64%. Direct oral anticoagulants are non-inferior to warfarin in preventing stroke in non-valvular AF, but have a lower risk of fatal intracranial haemorrhage. We determined how many patients discharged with a diagnosis of ischaemic stroke and AF were prescribed OAC, and established reasons for, and associations with, non-prescription of OAC.

All patients discharged with a diagnosis of ischaemic stroke and AF during the four-year period between 2013 and 2016 within NHS Highland were included in the study. Patients who started OAC after a period of treatment with antiplatelets were considered as being treated with OAC. Electronic patient records provided demographics, CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores and information on why patients were not started on OAC.

A total of 181 patients were discharged with a diagnosis of ischaemic stroke and AF over the study period: 52.5% (n=95) were female (p=0.45); 35.4% (n=64) were discharged without OAC. The median CHA2DS2-VASc score for patients not treated with OAC was 5 (interquartile range [IQR] 4–6). The median HAS-BLED score was 3 (IQR 2.5–4). There was no difference in rate of OAC prescription between men and women (67% vs. 62%, p=0.45). Patients 80 years of age or older were significantly less likely to be prescribed OAC on discharge than those under 80 years (54% vs. 76%, p=0.002). The two most common reasons for withholding OAC were concern over bleeding risk and falls. Patients treated at a hospital with a stroke unit were no more likely to be discharged on OAC compared with those treated at hospitals without a stroke unit (66% vs. 62%, p=0.64). Of patients not treated with OAC, 64% (n=41) were discharged on long-term antiplatelet drugs.

In conclusion, raising awareness of the relatively low risk of major bleeding, even in elderly patients and in those at risk of falls, might help increase OAC usage and reduce recurrent strokes.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) increases an individual’s risk of stroke fivefold.1 Oral anticoagulation (OAC) with warfarin reduces the risk of stroke by 64%.2 Novel or direct oral anticoagulants are non-inferior to warfarin in preventing stroke in non-valvular AF and have a similar bleeding profile, but with a lower risk of fatal intracranial haemorrhage and several practical advantages.3-7 While several antiplatelet agents have been shown to reduce the risk of recurrent stroke, they are considerably less effective than OAC, with a similar risk of major bleeding, and, therefore, are no longer recommended in national guidelines for stroke prevention in AF.8

Current guidelines for AF recommend that stroke risk is estimated using the CHA2DS2-VASc score.9 It is recommended that men with a score ≥1 or women with a score ≥2 should be treated with OAC, unless there is significant bleeding risk.10 Bleeding risk can be estimated using a number of different scoring systems. One of the most commonly used is the HAS-BLED score.11

Data from the Scottish Stroke Care Audit showed that, in Scotland, 68% of patients discharged with a diagnosis of ischaemic stroke and a diagnosis of AF are discharged with OAC, or start OAC after their first outpatient clinic visit.12 Thus, 32% were not anticoagulated and, therefore, remained at high risk of recurrent stroke.

NHS Highland covers a large geographical area in the north of Scotland, with three main hospitals and one stroke unit. Whether there are differences between those hospitals with and without a stroke unit in terms of OAC prescription is unknown.

The aims of this case-series review were twofold. First, to determine how many patients discharged with a diagnosis of ischaemic stroke and AF were prescribed OAC, and, second, to establish reasons for, and associations with, non-prescription of OAC.

Method

Design

This is a retrospective case-series review.

Setting

NHS Highland is the largest geographical health board in the UK covering an area of 32,593 km2 with a dispersed resident population of around 320,298 – just over 6% of the total population.13 Of the three largest hospitals in NHS Highland (Raigmore Hospital, Caithness General Hospital and Belford Hospital), only Raigmore Hospital has a designated stroke unit.

Sample

All patients discharged with a diagnosis of ischaemic stroke and AF during a four-year period between 2013 and 2016 within NHS Highland were included in the study. Patients were identified using data from the Scottish Stroke Care Audit.12

Patients who died during admission, had a haemorrhagic stroke or haemorrhagic transformation, and re-admissions were excluded. All patients who, at the time of the study, were still inpatients were excluded. Patients who were discharged on antiplatelet therapy but went on to start OAC within a month were considered as being treated with OAC.

Data handling

Electronic patient records provided patient demographics and information on why patients were not started on OAC. CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores were calculated for each patient using information from electronic patient records.

All data were collated and recorded in Microsoft Office Excel 2010. Statistical tests and graphs were performed using GraphPad Prism (Version 5, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to characterise the sample. D’Agostino-Pearson (omnibus K2) normality test was used to determine if data were from a Gaussian distribution. Mean and standard deviation (SD) were used for parametric data and median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-parametric data. Mann-Whitney U-test was used for all statistical analysis comparing categorical data.

Results

A total of 181 inpatients were discharged with a diagnosis of ischaemic stroke and AF over the four-year study period. Of these, 52.5% (n=95) were female (p=0.45); and the age range was normally distributed (mean age 80.0 years, SD 8.3 years). Of these patients, 35.4% (n=64) were discharged without an OAC. The median CHA2DS2-VASc score for patients not treated with OAC was 5 (IQR 4–6). The median HAS-BLED score was 3 (IQR 2.5–4).

Gender and age

There was no difference in rate of OAC prescription between men and women (67% vs. 62%, p=0.45). The median age of patients who did not receive an OAC was 84 years (IQR 78–89) versus 78 years (IQR 73–85) for those who were treated with OAC (Mann-Whitney U 2-tailed p=0.0005). Patients 80 years of age or older were significantly less likely to be prescribed OAC on discharge (54% vs. 76%, p=0.002) (table 1).

Reasons for OAC non-prescription

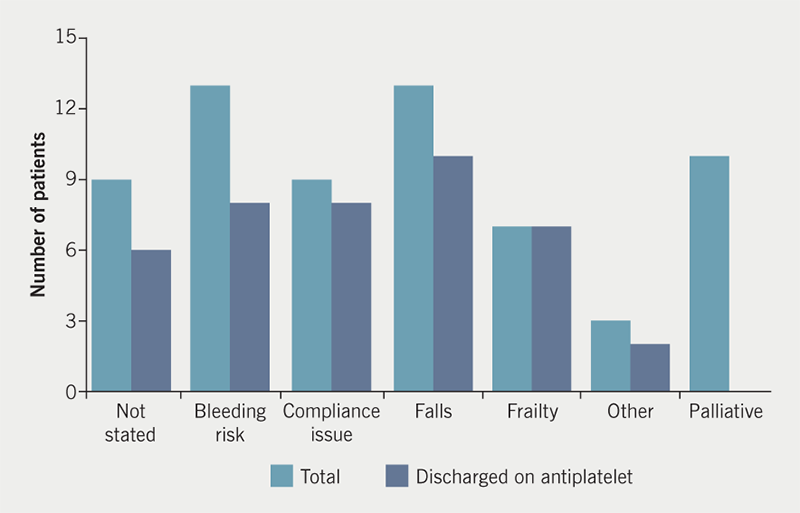

The two most common reasons for withholding OAC were concern over bleeding risk and falls. The reason for withholding OAC was not documented in nine patients (figure 1).

Stroke unit and year of discharge

Patients at Raigmore Hospital (which has a stroke unit) were no more likely to be discharged on OAC compared with those at Caithness and Belford hospitals (which have no stroke unit) (66% vs. 62%, p=0.64).

There was a non-significant trend suggesting patients admitted in 2015 and 2016 were more likely to be discharged on OAC compared with those admitted in 2013 and 2014 (71% vs. 58%, p=0.07).

Of the patients who were not treated with OAC, 64% (n=41) were discharged on long-term antiplatelet therapy.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

In our population, 36% of patients with AF did not receive OAC after an admission with stroke. This finding was similar to that in the national Scottish Stroke Care Audit (32%).12 This current case review describes why OAC was not prescribed on discharge in our patients with AF.

The main concern around long-term use of OAC was the risk of major bleeding and falls. Previous studies have shown that concerns over falls risk is the main reason for withholding OAC in elderly patients with AF.14 It is, therefore, not surprising that concerns over high bleeding risk and falls risk were the most commonly cited reasons for withholding OAC. However, although falls risk remains a concern for physicians when making decisions on OAC, this is not supported by published evidence. A prospective study, involving 515 patients discharged on warfarin, did not show any increase in bleeding among those at high risk of falls.15 Another study has suggested that the risk of subdural haematoma from falls in elderly patients on warfarin is almost negligible.16

The patients in whom OAC was withheld had a median CHA2DS2-VASc score of 5, equating to an annual stroke risk of 6.7%.8 The median HAS-BLED score was 3, equating to a bleeding risk of 5.8%, since many of the non-modifiable risk factors for stroke and bleeding are the same.10

Despite concerns around the use of oral OAC and bleeding risk, the majority of patients who were not prescribed OAC were discharged on long-term antiplatelet therapy. This warrants review, as it is well established that antiplatelet drugs are significantly inferior to OAC in preventing stroke in patients with AF.1,9,17 The BAFTA (Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged) trial randomised 973 patients over the age of 75 with AF to warfarin or aspirin.17 As well as demonstrating superiority of warfarin over aspirin in preventing stroke or death, the study also found no difference in the incidence of major haemorrhage between the two groups. This finding was also seen in a randomised-controlled trial comparing warfarin with aspirin in all patients with stroke, which found no increase in major bleeding but a significant increase in minor bleeding (20.8 vs. 12.9 minor bleeds per 100 patient-years).18 A meta-analysis comparing warfarin and aspirin in patients with AF demonstrated a modest increase in major bleeding risk with warfarin (2.2 vs. 1.3 events per 100 patient-years).19

Furthermore, non-prescription of OAC is strongly associated with increased mortality. An observational study of 1,459 older patients in the US with stroke and non-valvular AF found 42.5% of those not receiving OAC had died versus 19.1% of those treated with OAC, one year after discharge.20

While the decision on whether to start OAC in patients with AF needs to be made on an individual basis, the findings from this study suggest that there is considerable concern among physicians about prescribing OAC to elderly patients, who would otherwise benefit from the reduction in risk of a further stroke. Despite evidence of inferiority to OAC in terms of stroke prevention, most of these patients were treated with either aspirin or clopidogrel long term. It is likely that in older patients the co-administration of antiplatelet and OAC is more likely to result in major bleeding. Historically, in patients with pre-existing coronary artery stents, there may be a tendency to favour antiplatelet therapy over a combination of antiplatelet and OAC. However, current European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines recommend that in patients one year distant from coronary artery stent placement, OAC can be prescribed as monotherapy, where there is a long-term indication for OAC.21

This current study did show a trend to increased OAC in more recent years, and this may be seen as encouraging, however, non-prescription remains high, despite several local presentations and internal audits. This perhaps reflects a need for a cultural change around OAC prescription in older patients at risk of falls.

Limitations

The findings in this study are likely to be an under-representation of the true number of patients at risk of recurrent stroke from AF, since current practice does not include prolonged arrhythmia monitoring in patients with cryptogenic stroke in sinus rhythm. It is estimated that with prolonged monitoring a further 9% of all patients would be identified as having AF.22 This was a single-region study, however, the population studied is likely to be similar to the rest of the UK, and the results of the local audit were close to those in the Scottish Stroke Care Audit.

Conclusion

There would appear to be a need for an increased awareness among physicians treating elderly patients with stroke of the evidence for risk and benefit of antiplatelets agents and OAC. While it is encouraging that there was a trend towards increased prescription of OAC over the course of the last four years, current practice remains unduly conservative with regard to OAC prescription. Prescribers should be challenged about their perception of risk, and how this is communicated effectively with patients, to achieve a reduction in recurrent stroke risk.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Study approval and consent

This was a service evaluation using routinely collected data and, therefore, formal ethical approval was not required. Local Caldecott approval was obtained to use patient’s data.

Key messages

- A large proportion of patients with ischaemic stroke and atrial fibrillation (AF) are not treated with oral anticoagulation (OAC) on discharge from hospital

- The main reasons for withholding OAC are concerns over falls and increased bleeding

- Older patients are less likely to be prescribed OAC on discharge

- Most patients, deemed too high risk for OAC, were treated with antiplatelet therapy

- Antiplatelet therapy is inferior to OAC in preventing recurrent stroke with a comparable risk of major bleeding

- Raising awareness of the relatively low risk of major bleeding, even in elderly patients and in those at risk of falls, might help improve OAC usage, especially in the era of newer direct OAC

References

1. Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham study. Stroke 1991;359:983–8. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.22.8.983

2. Hart R, Pearce L, Aguilar M. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:857–67. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00007

3. Ruff C, Giugliano R, Braunwald E et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 2014;383:955–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0

4. Granger C, Alexander J, McMurray J et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365:981–92. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1107039

5. Patel M, Mahaffey K, Garg J et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365:883–91. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1009638

6. Giugliano R, Ruff C, Braunwald E et al. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2013;369:2093–104. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1310907

7. Connolly S, Ezekowitz M, Yusuf S et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1139–51. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0905561

8. Royal College of Physicians. National clinical guideline for stroke, 5th edition. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2016. Available from: https://www.strokeaudit.org/Guideline/Full-Guideline.aspx

9. Friberg L, Rosenqvist M, Lip GY. Evaluation of risk stratification schemes for ischaemic stroke and bleeding in 182 678 patients with atrial fibrillation: the Swedish Atrial Fibrillation cohort study. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1500–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehr488

10. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2893–962. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210

11. Lip GY, Frison L, Halperin JL, Lane DA. Comparative validation of a novel risk score for predicting bleeding risk in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation: the HAS-BLED (Hypertension, Abnormal Renal/Liver Function, Stroke, Bleeding History or Predisposition, Labile INR, Elderly, Drugs/Alcohol Concomitantly) score. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:173–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.024

12. NHS National Services Scotland. Scottish Stroke Care Audit. Available at: http://www.strokeaudit.scot.nhs.uk/

13. National Records of Scotland. Scotland’s census 2011. Available at: www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk [accessed 7 December 2017].

14. Dharmarajan TS, Varma S, Akkaladevi S et al. To anticoagulate or not to anticoagulate? A common dilemma for the provider: physicians’ opinion poll based on a case study of an older long-term care facility resident with dementia and atrial fibrillation. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2006;7:23–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2005.08.002

15. Donze J, Clair C, Hug B et al. Risk of falls and major bleeds in patients on oral anticoagulation therapy. Am J Med 2012;125:773–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.01.033

16. Man-Son-Hing M, Nichol G, Lau A et al. Choosing antithrombotic therapy for elderly patients with atrial fibrillation who are at risk for falls. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:677–85. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.159.7.677

17. Mant J, Hobbs F, Fletcher K et al. Warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in an elderly community population with atrial fibrillation (the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged Study, BAFTA): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007;370:493–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61233-1

18. Mohr JP, Thompson JLP, Lazar RM et al. A comparison of warfarin and aspirin for the prevention of recurrent ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1444–51. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa011258

19. van Walraven C, Hart R, Singer D et al. Oral anticoagulants vs aspirin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: an individual patient meta-analysis. JAMA 2002;288:2441–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.19.2441

20. McGrath ER, Go AS, Chang Y et al. Use of oral anticoagulation therapy in older adults with atrial fibrillation after acute ischaemic stroke. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:241–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14688

21. Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA et al. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS: the Task Force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2017;39:213–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx419

22. Wachter R, Gröschel K, Gelbrich G et al. Holter-electrocardiogram-monitoring in patients with acute ischaemic stroke (Find-AFRANDOMISED): an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2017;16:282–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30002-9