Drug-eluting stents (DES) are a common treatment for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) but pose risks like bleeding, re-stenosis, stent thrombosis, and neo-atherosclerosis. Drug-coated balloons (DCB) may mitigate these risks. This study compares DCB therapy’s effectiveness with DES in ACS patients with de novo lesions.

A retrospective observational study was conducted on ACS patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with either DES or DCB from May 2019 to August 2022 at a single tertiary centre. Patients with left central trunk lesions were excluded. The primary end point was a composite of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), cardiac death, myocardial infarction, and target lesion revascularisation, evaluated 12 months post-intervention. Statistical analysis was performed using R software with significance set at a two-tailed p value <0.05.

Of 168 patients, 101 received DES and 67 received DCB. The DCB group had a mean age of 61.9 years, while the DES group averaged 63 years. The DCB group had more prior PCIs and myocardial infarctions. Baseline characteristics, including target and number of lesions, were comparable. MACE occurred in eight (11.9%) DCB patients and 11 (10.9%) DES patients, showing no significant difference (p=0.64).

In conclusion, this study suggests that DCB therapy may be an effective alternative to DES for ACS. However, limitations, including a single-centre setting and short follow-up, warrant the need for more extensive, randomised trials to validate these findings.

Introduction

The management of coronary artery disease (CAD) in patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes (ACS) poses a significant challenge in interventional cardiology.1 As clinical practice evolves, the imperative to compare the outcomes of drug-coated balloons (DCB) and drug-eluting stents (DES) has gained prominence, particularly considering the distinct pathophysiological characteristics and risks associated with ACS.2

Insights from the BASKET-SMALL 2 trial, the largest randomised clinical trial assessing DCB versus DES for small-vessel CAD, provide pivotal evidence in this area. This prespecified analysis yielded three significant findings. First, there was no interaction between the indication for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), acute or chronic coronary syndrome, and the DCB versus DES treatment effect in small-vessel CAD patients. Second, the efficacy and safety of DCBs were sustained at three-year follow-up for both ACS and chronic coronary syndrome (CCS) patients, showing no significant differences in outcomes based on clinical presentation. Third, although all-cause mortality was higher in ACS patients throughout the follow-up, this did not differ significantly between those treated with DES or DCB, thus, reinforcing the safety profile of paclitaxel-coated balloons in these interventions.2 Given that 28.2% of trial participants were treated for ACS, 16.4% of whom presented with troponin-positive ACS, these findings are particularly relevant.2 Previous research has suggested that DCBs may exhibit noninferiority or even superiority to DES based on angiographic end points. For example, the PICCOLETO II trial highlighted the angiographic success of DCBs in a cohort with a substantial proportion of ACS patients, demonstrating reduced late lumen loss compared with everolimus-eluting stents.3

While the BASKET-SMALL 2 trial confirmed comparable rates of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) between DCB and DES, it also revealed distinctions in outcomes that merit further exploration. Importantly, at one-year follow-up, there was a significant interaction between treatment and clinical presentation regarding cardiac death and nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), with DCB-treated ACS patients experiencing the lowest rates of these adverse events.2 This exploratory finding suggests that DCB treatment may be particularly beneficial for ACS patients, especially considering that those on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) at discharge showed higher rates of continued DAPT use at one year. Further supporting the efficacy of DCBs, recent trials such as PEPCAD NSTEMI and REVELATION have demonstrated the noninferiority of DCB treatment in ACS contexts, reinforcing the notion that DCB strategies can serve as effective alternatives to DES.4,5 Significantly, avoiding permanent implants with DCBs mitigates the risks of stent-related complications, such as stent thrombosis, a critical concern in ACS where coronary vasodilator mechanisms are often impaired.6,7

Despite some concerns regarding increased mortality associated with paclitaxel devices in peripheral artery disease, no such associations have been observed in the coronary context, with meta-analyses indicating that DCBs do not elevate mortality rates compared with alternative treatments.5,8 Building on current evidence, our study looks at real-world outcomes in ACS patients who received either DCB or DES during PCI at a single tertiary centre, without limiting to small-vessel CAD. By focusing on a broader ACS population, our study fills a significant gap, examining how DCBs perform in complex, real-life cases, where traditional stents might not be ideal. This approach helps us better understand DCB’s potential as an alternative in ACS care, offering practical insights to support clinicians in managing diverse coronary presentations.

Method

Study design and population

This retrospective observational study was conducted at Manchester Royal Infirmary, focusing on consecutive patients diagnosed with ACS who underwent PCI between May 2019 and August 2022. Eligible patients included those who met the following criteria: aged 18 years or older; presenting with either ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) or unstable angina (UA); and treated with either DCB or DES. Patients with left main trunk lesions were excluded. This study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Interventional procedure

All PCI procedures were conducted by established international guidelines and local protocols. Before the intervention, each patient received a loading dose of 300 mg aspirin, 300–600 mg clopidogrel, 180 mg ticagrelor, or 60 mg prasugrel, based on individual risk profiles and STEMI guidelines. Unfractionated heparin was administered intravenously as an initial 100 IU/kg body weight bolus, with additional doses provided to maintain an activated clotting time of ≥250 seconds throughout the procedure.

The decision to utilise DCB or DES was made at the operator’s discretion, considering device length and diameter, inflation time and pressure, and adjunctive measures like intra-aortic balloon pumps or thrombus aspiration. A successful procedure was defined as achieving a post-procedural residual stenosis of ≤30%. In cases where significant flow-limiting dissections or residual stenosis greater than 30% were observed following DCB placement, bailout stenting was performed. Post-procedure, all patients were prescribed DAPT, which included aspirin (100 mg daily) in combination with either clopidogrel (75 mg daily), ticagrelor (90 mg twice daily), or prasugrel (60 mg loading dose followed by 10 mg daily), depending on their clinical profile. DAPT was recommended for three to six months following DCB use and for 12 months in patients who received DES.

End points and definitions

The primary end point was defined as a composite of MACE, which included cardiac death, target vessel MI and target lesion revascularisation (TLR). Cardiac deaths were classified as such, unless a clear noncardiac cause was documented. MI was defined by recurrent ischaemic symptoms lasting at least 30 minutes, accompanied by new electrocardiographic (ECG) changes or elevated troponin levels. TLR was classified as any repeat percutaneous intervention or surgical revascularisation of the target lesion area due to complications, such as re-stenosis or stent thrombosis. Major bleeding was defined based on criteria established by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH).

Clinical follow-up

Clinical follow-up was conducted rigorously through comprehensive reviews of hospital records and outpatient visits at discharge and 30 days, three months, six months, and 12 months post-procedure. All adverse events were evaluated by independent physicians who were not involved in the interventions, ensuring an objective assessment of outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared using Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney rank-sum test, as appropriate. Categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages and analysed using Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. Event-free survival rates were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared via the log-rank test. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted utilising R software.

Results

Patient characteristics and procedural indications

Overall, 67 patients received DCB, while 101 patients were treated with DES. The primary indication for PCI was similar between the two groups, with NSTEMI or UA accounting for 68.7% of DCB cases and 71.3% of DES cases (p=0.740) (table 1). STEMI was observed in 31.3% of the DCB group and 28.7% of the DES group (p=0.825).

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) stratified by the use of either drug-coated balloons (DCB) or drug-eluting stents (DES)

| Characteristic | DCB N=67 |

DES N=101 |

p value |

| Mean age ± SD, years | 61.9 ± 10.9 | 63.0 ± 11.7 | 0.178 |

| Male, n (%) | 50 (74.6) | 81 (80.2) | 0.432 |

| CAD history, n (%) | |||

| Previous MI | 60 (89.6) | 35 (34.7) | 0.045 |

| Previous CABG | 7 (10.4) | 8 (7.9) | 0.685 |

| Previous PCI | 45 (67.2) | 52 (51.5) | 0.032 |

| Previous stroke | 17 (25.4) | 9 (8.9) | 0.036 |

| CAD risk factors, n (%) | |||

| Diabetes (oral) | 17 (25.4) | 29 (28.7) | 0.715 |

| Diabetes (insulin) | 7 (10.4) | 7 (6.9) | 0.534 |

| Chronic renal failure: dialysis | 2 (3.0) | 3 (3.0) | 1 |

| Family history of CAD | 7 (10.4) | 6 (5.9) | 0.482 |

| Known hypercholesterolaemia | 33 (49.2) | 55 (54.5) | 0.678 |

| Known hypertension | 41 (61.2) | 66 (65.4) | 0.412 |

| Known PVD | 8 (11.9) | 6 (5.9) | 0.268 |

| LVEF, n (%) | |||

| Good (>50%) | 30 (44.8) | 43 (42.3) | 0.835 |

| Moderate (30–50%) | 17 (25.4) | 24 (23.8) | 0.896 |

| Poor (<30%) | 9 (13.4) | 12 (11.9) | 0.806 |

| Not measured | 11 (16.4) | 19 (18.8) | 0.842 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||

| Current smoker | 22 (32.8) | 30 (29.7) | 0.739 |

| Ever smoked | 44 (65.7) | 56 (55.4) | 0.276 |

| Never | 23 (34.3) | 45 (44.6) | 0.27 |

| Valvular heart disease, n (%) | 4 (6.0) | 5 (4.9) | 0.845 |

| NYHA functional class >3, n (%) | 9 (13.4) | 7 (6.9) | 0.189 |

| Discharge diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| NSTEMI/unstable angina | 46 (68.7) | 72 (71.3) | 0.740 |

| STEMI | 21 (31.3) | 29 (28.7) | 0.825 |

| Key: CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD = coronary artery disease; DCB = drug-coated balloon; DES = drug-eluting stent; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; MI = myocardial infarction; NSTEMI = non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; NYHA = New York Heart Association; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; PVD = peripheral vascular disease; SD = standard deviation; STEMI = ST-elevation myocardial infarction | |||

Pre-procedure characteristics

Pre-procedural characteristics revealed significant differences in Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow grades. In the DCB group, 44.8% of patients presented with TIMI 0 flow, compared with 51.5% in the DES group (p=0.021) (table 1). A higher proportion of patients in the DCB group presented with cardiogenic shock pre-procedure (four patients) compared with the DES group (three patients), but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.675). The vascular access method varied, with the radial approach being predominant in both groups: 92.5% in the DCB group versus 80.2% in the DES group (p=0.005). Femoral access was utilised in five DCB and 20 DES patients (p=0.022).

Procedural details

The vessels targeted for PCI included the left anterior descending artery (LAD), right coronary artery (RCA), and left circumflex artery (LCx). In the DCB group, PCI was performed on the LAD in 22 patients, the RCA in 18, and the LCx in 19. The DES group showed a higher frequency of RCA interventions (39 patients) compared with LAD (20 patients) (p=0.028) (table 1). Balloon pre-dilatation was successfully performed with a mean length of 17.9 ± 2.5 mm and a diameter of 2.9 ± 0.6 mm for DCB. In comparison, the DES group had a slightly longer balloon length (18.2 ± 2.6 mm) but a smaller diameter (2.7 ± 0.6 mm), with no significant difference in length (p=0.497) or diameter (p=0.285).

Antithrombotic therapy

The choice of antithrombotic agents indicated a trend towards more frequent use of heparin alone in the DCB group (69.3%) compared with DES (62.7%) (p=0.043) (table 2). For STEMI patients, standard guidelines recommend the use of DAPT, including aspirin in combination with either clopidogrel or prasugrel, depending on patient risk profiles. In this study, 37.3% of patients in the DCB group received heparin in combination with GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors, compared with 30.7% in the DES group (p=0.492).

Table 2. Procedural characteristics of ACS patients stratified by the use of either a DCB or a DES

| Characteristic | DCB N=67 |

DES N=101 |

p value |

| Indication for PCI, n (%) | |||

| NSTEMI/unstable angina | 46 (68.7) | 72 (71.3) | 0.740 |

| STEMI | 21 (31.3) | 29 (28.7) | 0.825 |

| Q-wave on presenting ECG | 5 (7.5) | 14 (13.9) | 0.228 |

| Arterial access, n (%) | |||

| Femoral | 5 (7.5) | 20 (19.8) | 0.022 |

| Radial | 62 (92.5) | 81 (80.2) | 0.005 |

| Pre-procedure TIMI flow, n (%) | |||

| TIMI 0 | 30 (44.8) | 52 (51.5) | 0.021 |

| TIMI 1 | 10 (14.9) | 20 (19.8) | 0.473 |

| TIMI 2 | 21 (31.3) | 31 (30.7) | 0.947 |

| TIMI 3 | 6 (9.0) | 12 (11.9) | 0.573 |

| Cardiogenic shock pre-procedure, n (%) | 4 (6.0) | 3 (3.0) | 0.675 |

| Vessel attempted, n (%) | |||

| LAD | 22 (32.8) | 20 (19.8) | 0.034 |

| RCA | 18 (26.9) | 39 (38.6) | 0.028 |

| LCx | 19 (28.4) | 18 (17.8) | 0.058 |

| Grafts | 1 (1.5) | 4 (4.0) | 0.379 |

| MVD | 7 (10.4) | 20 (19.8) | <0.001 |

| Balloon pre-dilatation, mm | |||

| Mean length ± SD | 17.9 ± 2.5 | 18.2 ± 2.6 | 0.497 |

| Mean diameter ± SD | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 0.285 |

| Antithrombotic agent used, n (%) | |||

| Heparin only | 46 (69.3) | 63 (62.7) | 0.043 |

| Heparin + GPIIb/IIIa | 25 (37.3) | 31 (30.7) | 0.492 |

| Bivalirudin | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Warfarin | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Any circulatory support, n (%) | |||

| IABP used | 4 (6.0) | 3 (3.0) | 0.675 |

| Ventilated | 3 (4.5) | 2 (2.0) | 0.464 |

| Post-procedure TIMI flow, n (%) | |||

| TIMI 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.493 |

| TIMI 1 | 5 (7.5) | 4 (4.0) | 0.426 |

| TIMI 2 | 12 (17.9) | 15 (14.9) | 0.599 |

| TIMI 3 | 49 (73.1) | 82 (81.2) | 0.024 |

| Vascular closure device, n (%) | 23 (34.3) | 45 (44.5) | 0.013 |

| Arterial complication, n (%) | 4 (6.0) | 3 (3.0) | 0.675 |

| Major bleed, n (%) | 2 (3.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0.576 |

| Bailout stenting, n (%) | 2 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.124 |

| Key: DCB = drug-coated balloon; DES = drug-eluting stent; ECG = electrocardiograph; IABP = intra-aortic balloon pump; LAD = left anterior descending; LCx = left circumflex; MVD = multi-vessel disease; NSTEMI = non-ST-elevation myocardial Infarction; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA = right coronary artery; SD = standard deviation; STEMI = ST-elevation myocardial infarction; TIMI = Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction | |||

Post-procedure outcomes

Post-procedure TIMI flow assessments demonstrated essential differences. While 73.1% of patients in the DCB group achieved TIMI 3 flow, this was significantly higher in the DES group (81.2%) (p=0.024) (table 2). The DCB group experienced one case of TIMI 0 flow post-procedure, while the DES group had none. Vascular closure devices were utilised in 34.3% of the DCB group compared with 44.5% in the DES group (p=0.013). Adverse events included four arterial complications in the DCB group and three in the DES group (p=0.675). Major bleeding events were reported in two patients treated with DCB and in one patient treated with DES (p=0.576). Bailout stenting occurred in two patients in the DCB group compared with none in the DES group (p=0.124).

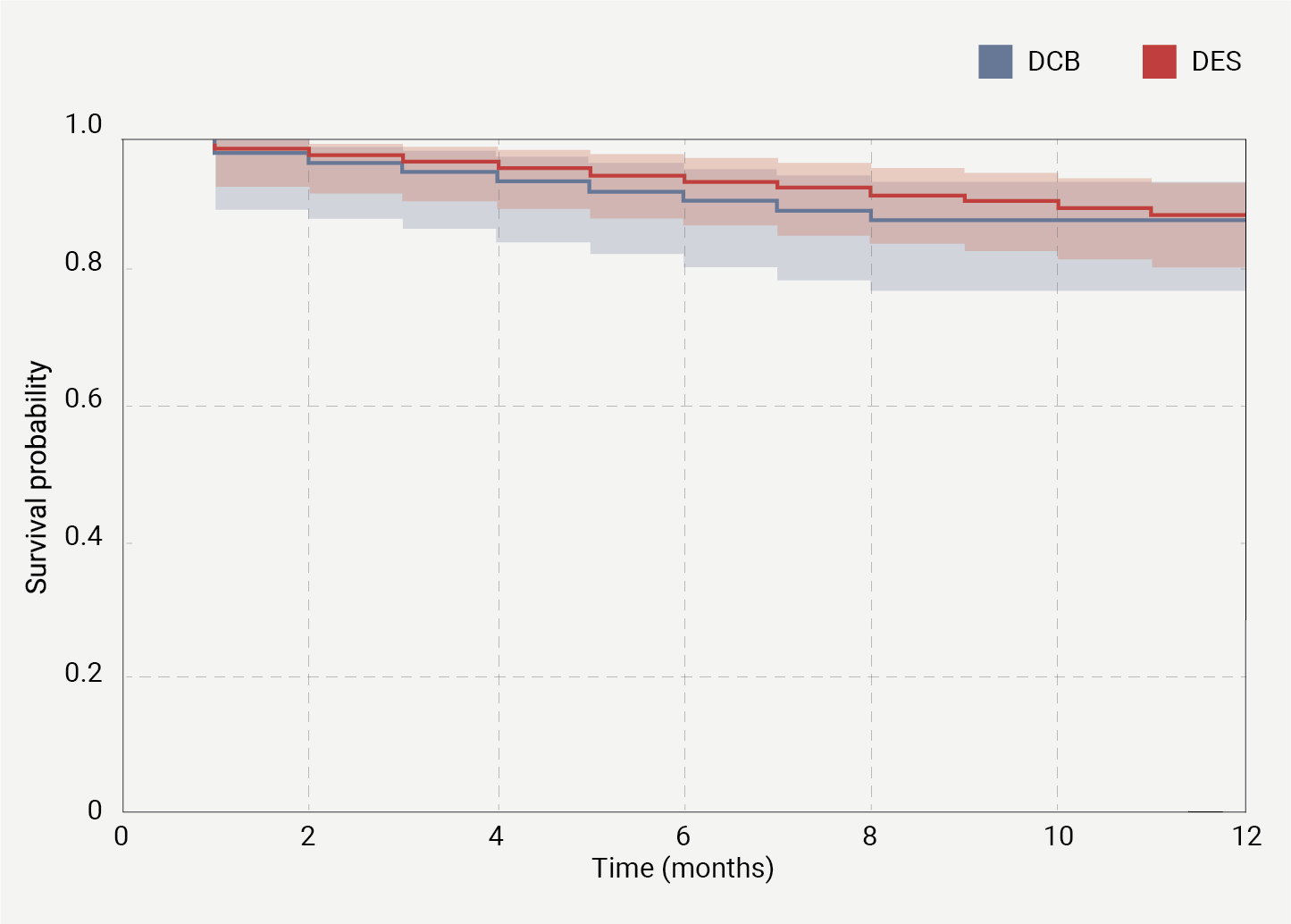

Kaplan-Meier analysis

The Kaplan-Meier plot (figure 1) demonstrates no significant difference in MACE between the DCB and DES groups, with a p value of 0.64, indicating similar long-term outcomes for both treatment modalities.

| The Kaplan-Meier survival curves compare the cumulative survival probability free from MACE over a 12-month period between patients treated with drug-coated balloon (DCB) (blue line) and those treated with drug-eluting stent (DES) (red line). The shaded areas around each line represent the 95% confidence intervals. The two groups show similar survival probabilities, with no significant difference (p=0.64) observed between the DCB and DES groups. The survival probability remains above 0.8 for both groups throughout the follow-up period, indicating generally high survival rates free from MACE events. |

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the safety and efficacy of DCB compared with DES in patients presenting with ACS. Our findings support a growing body of evidence supporting DCB as a viable alternative to DES.8-10 Importantly, our study highlights that DCB therapy may be effective in a broader, unselected ACS population, and is not limited to cases with small-vessel lesions.

The demographic analysis revealed that both patient groups were well-matched, with mean ages of 61.9 years for the DCB cohort and 63.0 years for the DES cohort. Most patients in both groups were diagnosed with NSTEMI or UA, thereby emphasising the clinical significance of our findings. Additionally, comorbidities, such as prior MI and diabetes, were similarly distributed between the groups, further enhancing the robustness of our analysis. A significant finding of our study was the improvement in post-procedural TIMI flow, with DCB achieving TIMI 3 flow in 49% of cases. This improvement indicates effective reperfusion, particularly considering the initially lower TIMI flow observed in the DCB group.

Furthermore, the low incidence of major bleeding events, two cases in the DCB group compared with one in the DES group, highlights the favourable safety profile of DCB, which is critical in managing ACS patients. An essential aspect of our investigation was the incidence of bailout stenting, which occurred in two patients within the DCB cohort due to complications, one for acute vessel closure and another for a type D dissection following DCB angioplasty. This underlines the necessity for scrupulous lesion preparation before deploying DCB. While DCB have shown effectiveness in treating small-vessel lesions, careful monitoring is essential to mitigate the risk of acute complications.

Moreover, the inherent attribute of DCB to leave no permanent device behind may reduce some risks associated with conventional stenting, such as late stent thrombosis and re-stenosis, particularly relevant in younger patients who may be more susceptible to these complications. As suggested by the higher rate of heparin monotherapy in the DCB group, the potential for simplified antithrombotic strategies could further enhance patient safety and comfort. These findings are consistent with the existing literature, which has reported favourable clinical and angiographic outcomes associated with DCB across various populations.11,12 Our study contributes to this growing body of evidence by demonstrating that DCB may be an effective treatment option for small-vessel lesions in patients with ACS.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, as a retrospective observational analysis conducted at a single tertiary centre, the findings may not be generalisable to broader populations. The decision to utilise DCB or DES was made at the operator’s discretion, which may introduce selection bias. Variability in clinical practice and patient selection criteria could influence the outcomes observed. Second, while we aimed to match baseline characteristics between the DCB and DES groups, residual confounding may still exist. Factors such as variations in lesion complexity, operator experience, and differing approaches to post-procedural care may not have been fully accounted for, potentially impacting clinical outcomes. Third, the relatively small sample size limits the power of our analysis to detect differences in rare adverse events, such as bailout stenting and significant bleeding complications. This constraint hampers our ability to draw definitive conclusions regarding the safety and efficacy of DCB compared with DES. Additionally, the short follow-up duration of this study poses a challenge in assessing long-term outcomes. Although we captured significant early and mid-term events, the potential for late complications, such as stent thrombosis or late lumen loss, cannot be thoroughly evaluated in this context.

Finally, the heterogeneity in patient demographics and clinical presentations, including variations in infarct-related arteries and pre-procedural TIMI flow, may affect the comparability of the two groups. These differences highlight the complexity of treating ACS patients with small-vessel CAD and highlight the need for more extensive, multi-centre randomised-controlled trials to validate our findings.

Conclusion

In summary, our research suggests that DCB may provide a safe and effective alternative to DES for patients with ACS. The analysis demonstrated significant improvements in post-procedural TIMI flow and a favourable safety profile for DCB, alongside comparable rates of MACE compared with DES. It is essential to acknowledge certain limitations of our study, including its retrospective observational design and the potential for selection bias, which may influence the generalisability of the findings. Additionally, variations in patient demographics and clinical presentations were noted, accentuating the complexity of treating ACS patients. Given these considerations, while this study contributes valuable insights into the use of DCB in ACS management, further research is needed. Future large-scale, multi-centre randomised-controlled trials are crucial to validate our findings and enhance clinical decision-making regarding the use of DCB in a diverse range of ACS patients.

Key messages

- Comparable efficacy: drug-coated balloons (DCB) have exhibited comparable clinical results to drug-eluting stents (DES) in the management of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) involving de novo lesions. Notably, there are no statistically significant differences in major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) within a 12-month period between the two interventions

- Potential benefits of DCB: the utilisation of DCB therapy circumvents the need for permanent implants, thereby mitigating risks associated with in-stent re-stenosis, late stent thrombosis, and neo-atherosclerosis. This characteristic positions DCB as a compelling alternative to DES in clinical practice

- Clinical considerations: although DCB demonstrate a favourable safety profile, meticulous preparation of lesions is essential to reduce the incidence of bailout stenting. Furthermore, the application of DCB may permit a reduction in the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy

- Future research needed: the retrospective, single-centre nature of the study, combined with the abbreviated follow-up duration, underscores the necessity for larger, randomised-controlled trials to ascertain the long-term efficacy of DCB therapy in patients with ACS

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

SS is supported by the 4Ward North Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Training Fellowship (Grant Reference 203914/Z/16/Z).

Study approval

The ethics committee at the University of Manchester determined that approval was not required for this retrospective study.

References

1. Gu D, Qu J, Zhang H, Zheng Z. Revascularization for coronary artery disease: principle and challenges. Adv Exp Med Biol 2020;1177:75–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-2517-9_3

2. Jeger RV, Farah A, Ohlow MA et al. Drug-coated balloons for small coronary artery disease (BASKET-SMALL 2): an open-label randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2018;392:849–56. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3210892

3. Cortese B. The PICCOLETO study and beyond. EuroIntervention 2011:7(suppl K):K53–K56. https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJV7SKA9

4. Scheller B, Ohlow MA, Ewen S et al. Bare metal or drug-eluting stent versus drug-coated balloon in non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the randomised PEPCAD NSTEMI trial. EuroIntervention 2020;15:1527–33. https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJ-D-19-00723

5. Vos NS, Fagel ND, Amoroso G et al. Paclitaxel-coated balloon angioplasty versus drug-eluting stent in acute myocardial infarction: the REVELATION randomized trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2019;12:1691–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2019.04.016

6. Kundu A, Moliterno DJ. Drug-coated balloons for in-stent restenosis – finally leaving nothing behind for US patients. JAMA 2024;331:1011–12. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2024.0813

7. Her AY, Shin ES. Drug-coated balloon treatment for de novo coronary lesions: current status and future perspectives. Korean Circ J 2024;54:519–33. https://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2024.0148

8. Cortese B, Bertoletti A. Paclitaxel coated balloons for coronary artery interventions: a comprehensive review of preclinical and clinical data. Int J Cardiol 2012;161:4–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.08.855

9. Abdelaziz A, Hafez A, Atta K et al. Drug-coated balloons versus drug-eluting stents in patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: an updated meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2023;23:605. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-023-03633-w

10. Mangner N, Farah A, Ohlow MA et al. Safety and efficacy of drug-coated balloons versus drug-eluting stents in acute coronary syndromes: a prespecified analysis of BASKET-SMALL 2. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2022;15:e011325. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.121.011325

11. Jun EJ, Shin ES, Teoh EV et al. Clinical outcomes of drug-coated balloon treatment after successful revascularization of de novo chronic total occlusions. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022;9:821380. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.821380

12. Elgendy IY, Gad MM, Elgendy AY et al. Clinical and angiographic outcomes with drug‐coated balloons for de novo coronary lesions: a meta‐analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e016224. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.016224