Blackouts are common, affecting up to 50% of the population. However, little is known about the incidence and initial management of blackouts in primary care. A retrospective computerised search of the medical records of 16,911 patients in two UK practices found the incidence of first presentation with blackout to the GP to be 3.4/1,000 patients/year. Affected patients’ records were then individually reviewed to assess whether key aspects of National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) blackouts and European Society of Cardiology syncope guidelines had been followed during that initial consultation. GPs were generally better at enquiring about features that differentiate between vasovagal syncope and epilepsy. They were not as good at detecting syncope red flags, which help to identify the cardiac causes of syncope that are associated with higher mortality. Raising awareness of these red flags in primary care was recommended.

Introduction

Blackouts are common, affecting up to a half of the population at some stage during their lives. They cause 3% of Accident and Emergency (A&E) attendances and 1% of hospital admissions.1 Blackouts (or transient loss of consciousness [TLoC]) can be defined as loss of consciousness characterised by rapid onset, short duration, and spontaneous complete recovery, irrespective of mechanism. Blackouts can be subdivided by aetiology, and syncope is one such subgroup that specifically refers to blackout caused by transient global cerebral hypoperfusion.2 Reports commonly confuse the definition of blackouts and syncope, which are often incorrectly used interchangeably.3

Incidence of presentation with blackouts in primary care

There is no reliable information available regarding the numbers of patients who attend health professionals in primary care in the UK for first assessment of blackouts. Currently available statistics mostly relate to A&E attendances and hospital admissions.4

Vanbrabant et al.5 found the overall incidence of a first syncope to be 1.91/1,000 person-years in a large retrospective study of GP consultations in Belgium. However, they also included the term ‘blackout’ in their search criteria, and patients in Belgium often have more than one GP practice, so gauging precise practice populations was difficult.

In the Framingham population, the rate of first report of syncope was 6.2/1,000 person-years.6 However, transient ischaemic attack (TIA), stroke and seizure were included under the umbrella of ‘syncope’, and head injury was excluded, and, therefore, this group neither met the criteria for syncope nor blackout.

The first aim of the study was to determine the numbers of patients attending their GP in the UK for first assessment of blackout during a six-month period.

Initial assessment of patients with blackouts

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) transient loss of consciousness (blackouts) in over 16s (CG109) clinical guidance was first published in 2010 and reviewed in 2014.7 Some features of this guidance are particularly relevant to the GP’s initial assessment of patients who have experienced a blackout and include:

- factors that should be clarified in the patient history

- recommended patient examination

- initial investigations in primary care

- identification of red flags that require urgent specialist assessment.

Details that should be elicited from the history should include posture, prodrome, provocation, signs and symptoms of heart failure, and family history of sudden death under 40 years of age. In addition, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines on diagnosis and management of syncope 20092 recommend enquiry regarding symptoms of chest pain and palpitations preceding syncope to aid risk stratification.

Furthermore, NICE guidance is targeted at adults, whereas ESC guidance also includes recommendations regarding children.

NICE recommends that examination should include auscultation for a cardiac murmur, and lying and standing blood pressure measurements. A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) should be recorded in all unexplained blackouts, and ideally this should be with automated interpretation.

The second aim of this study was to determine whether GPs were following defined aspects of NICE 2010 and ESC 2009 guidelines relevant to primary care during this consultation.

Methods

The study was undertaken in two practices – one in a small Warwickshire town and the other in a suburban area of Birmingham. Patient list sizes were 5,425 and 11,486, respectively.

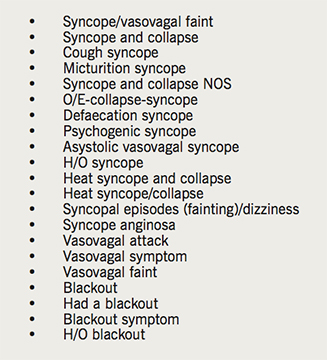

Records of patients of all ages who presented to GPs and nurse practitioners during the period 1 September 2015 to 1 March 2016 were sought retrospectively by computer search using EMIS software. The Read code search terms that were used are shown in box 1.

The medical records of individual patients found in the search were located, and consultations during the six-month period of the search were reviewed.

Patients were excluded from the audit for the following reasons.

- They had not experienced a true blackout.

- They were attending for review and had previously been assessed outside the timescale of the study.

- They presented first to hospital A&E where assessment and investigations were initiated.

- They were initially seen by paramedics who undertook a risk assessment and initial investigation.

Remaining patients’ records were reviewed and it was noted whether or not the GP or nurse practitioner had recorded the following information in the consultation from the patient or a witness:

- posture

- prodrome

- provocation

- family history of sudden death under age of 40 years

- signs and symptoms of heart failure

- palpitations

- chest pain

- cardiac murmur

- lying and standing blood pressures

- 12-lead ECG

- mode of ECG interpretation.

- In addition, the following details were recorded:

- date of birth

- whether the patient was referred to another service, e.g. A&E or outpatient clinic

- provisional diagnosis.

Results

From a total patient population of 16,911 patients, 48 patients were identified as having presented to the practice for assessment of TLoC according to the search criteria. Of these, 19 were subsequently excluded because, on review of their medical records, they had not experienced a true blackout, had previously been assessed outside the timescale of the audit or were initially assessed in A&E or by paramedics. Thereafter, 29 patients remained in the study. This is equivalent to a consultation rate for initial assessment of new onset blackouts of 3.4/1,000 patients per year.

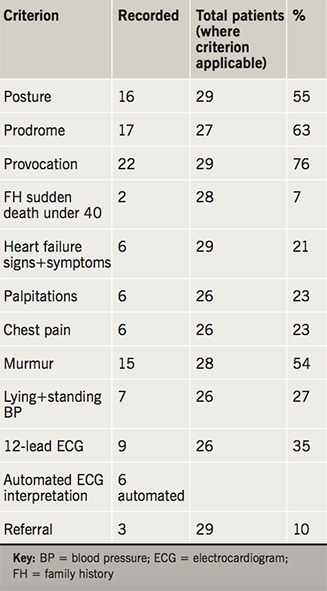

All patients were assessed by a GP, although one patient was initially assessed by a nurse practitioner before being seen by the GP. Two patients were under 16 years old (1 and 15 years of age). Results are shown in table 1.

It was not always possible to ask patients some of the relevant questions due to age or cognitive impairment. Some aspects of examination were not possible for the same reasons. For these criteria, the ‘total patients’ numbers were reduced to less than 29.

The % column is the number of patients where the criterion was recorded, shown as a percentage of the total number of patients from which it was possible to obtain this information.

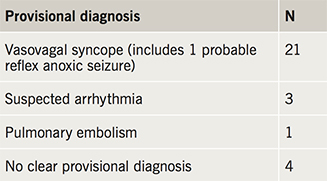

Provisional diagnoses at the end of the consultations are shown in table 2.

Of the 21 patients considered to have vasovagal syncope, provoking factors included a blood test, sight of blood, micturition, gastroenteritis, dehydration, heat, queuing, stress, alcohol, hunger and anaemia.

Three patients (10%) were referred to secondary care (one in an emergency ambulance). One further patient was already under appropriate secondary care services. One patient was offered referral, but declined. Although arrhythmia was suspected in another, due to the patient’s severe dementia and other co-existing medical problems, it was agreed with the family that referral was inappropriate.

There were no consultations in which all standards were met.

Discussion

The GPs in the study were generally good at recording the ‘3 Ps’ (posture, prodrome and provocation) that help to differentiate between vasovagal syncope and epilepsy7 (recorded in over 55–76% of included patients where obtaining this information was possible). This is encouraging, because the misdiagnosis rate in epilepsy patients is high. Scheepers et al. demonstrated that 23% of patients on long-term anticonvulsants for epilepsy had been misdiagnosed, and the most common alternative cause was a cardiovascular one.8 Epileptiform movement is common in vasovagal syncope and is likely to contribute to this confusion.1

However, GPs were not as good at recording the red flags for syncope that would precipitate an urgent specialist assessment of the patient. These red-flag criteria were recorded in under 7–54% of consultations. Chest pain, palpitations, and signs and symptoms of heart failure (such as breathlessness) were noted in under one quarter of TLoC consultations, and in only 7% did the GP record a family history of sudden death.

In nine cases out of 26 (where ECG recording was appropriate), a 12-lead ECG was recorded in primary care, and in six of these automated interpretation was used. Orthostatic recordings were made in only 27% of the patients where this was possible.

Patients with cardiac syncope are at risk of higher mortality.2 However, in only two cases of 26 were both a family history of sudden death under 40 and ECG recorded. Failing to do so is of clinical importance as both criteria would assist in detecting patients with inherited cardiomyopathy and channelopathy. Some of the provoking factors for vasovagal syncope such as stress, fright, exercise and posture can also be provoking factors for arrhythmia in channelopathies, and a family history or ECG would assist in differentiation between these conditions.

This study suggests that there is a need for providing education for primary-care professionals regarding assessment of patients with blackouts, especially in relation to syncope red flags. Cardiac arrest has been reported in patients with long QT syndrome that had been misdiagnosed as having epilepsy and treated with anticonvulsants, and 12-lead ECG would assist in highlighting such patients.6

A number of risk assessment tools used in ESC and NICE guidelines were developed in hospital settings and may not be entirely appropriate for use in primary care, and validation in this setting would be useful.

Although the NICE guidance may be considered the standard that is used in primary care, it contains some deficiencies. For example, red-flag assessment does not include enquiry regarding chest pain and palpitation prior to TLoC. In addition, blackouts while supine are not highlighted in this document and may indicate epilepsy or psychogenic pseudosyncope, but is also considered by some to be a red flag for arrhythmia in syncope.2 NICE blackouts guidance is not scheduled for review until October 2019, and perhaps it would be prudent to consider earlier review.

Study limitations

- Search parameters: patients with blackouts were identified using Read code searches of ‘problem titles’ recorded during consultations. However, rather than use Read codes such as ‘blackout’, ‘syncope’, ‘vasovagal syncope’ etc., the GP may have used alternative Read codes such as ‘palpitation’, ‘fall’ or ‘head injury’ instead. Blackout or syncope may have been written freetext in the consultation and not recorded as a Read code and, therefore, these patients would be omitted from the search. Sometimes GPs do not allocate any Read code to the consultation. Such factors are likely to cause underestimation of the incidence of blackouts presenting in primary care.

- A search for patients with new-onset epilepsy was not conducted. In general, this Read code is not applied until after investigations in secondary care have been completed. In retrospect, perhaps the term ‘convulsion’ may have been a useful inclusion.

- GPs may have asked about criteria included in this audit such as red flags, but not recorded this fact in the patient records.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Key messages

- Blackouts and syncope commonly present in primary care

- Syncope is commonly misdiagnosed as epilepsy

- In patients with blackouts, mortality is highest in those with a cardiac cause

- GPs were good at identifying features that help differentiate vasovagal syncope from epilepsy

- GPs need further training in identification of red flags in syncope

References

1. Petkar S, Cooper P, Fitzpatrick AP. How to avoid a misdiagnosis in patients presenting with transient loss of consciousness. Postgrad Med J 2006;82:630–41. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2006.046565

2. Task Force the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope, European Society of Cardiology (ESC), European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009). Eur Heart J 2009;30:2631–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehp298

3. Fitzpatrick AP, Cooper P. Diagnosis and management of patients with blackouts. Heart 2006;92:559–68. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2005.068650

4. Matthews IG, Lawson J, Parry SW, Davison J. A survey of the management of transient loss of consciousness in the emergency department. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2014;44:10–13. https://doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2014.103

5. Vanbrabant P, Gillet JB, Buntinx F, Bartholomeeusen S, Aertgeerts B. Incidence and outcome of first syncope in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Family Practice 2011;12:102. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-12-102

6. Soteriades ES, Evans JC, Larson MG et al. Incidence and prognosis of syncope. N Engl J Med 2002;347:878–85. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa012407

7. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Transient loss of consciousness (‘blackouts’) in over 16s. CG109. London: NICE, August 2010. Last update September 2014. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg109

8. Scheepers B, Clough P, Pickles C. The misdiagnosis of epilepsy: findings of a population study. Seizure 1998;7:403–06. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1059-1311(05)80010-X