The incidence of statin intolerance due to non-severe side effects is estimated to be 5–10%. As an increasing number of patients become eligible for lipid-lowering treatment, this is becoming a more prevalent issue. Very limited, if any, data exist so far in the management of this subgroup of patients. Clinic letters from 1,100 patients who attended the Lipid Clinic at Hull Royal Infirmary from January 2000 until December 2004 were searched for ‘statin intolerance’. Forty patients (19 male, 21 female, median age 62 years) were identified with intolerance to at least one statin drug but with an absolute indication to be on treatment. Out of the 40 patients, 26 (65%, 11 male, 15 female) were eventually able to tolerate a statin for at least six months without their initial side effect, the most commonly successful statins being rosuvastatin (n=9) and pravastatin (n=8). Overall, this required a median of two switches (range one to four) in statin treatment. Fourteen (35%) were unable to continue treatment after a median of 1.5 switches (range one to three), either because of continued intolerance or a decision not to proceed with more alternatives. In conclusion, nearly two thirds of patients with initial problems with a particular statin are able to take an alternative statin without side effects. This supports the trial of different statins in intolerant patients.

Introduction

It is estimated that 2.5 million patients in the UK currently take statin drugs for both primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease, and this number is likely to rise substantially with the lowering of treatment thresholds.1

As an increasing number of patients become eligible for lipid-lowering treatment, there is an increasing number who appear to be intolerant to individual statins. Indeed, though statins are known to be well tolerated and safe as elucidated in clinical trials, in the real world the incidence of statin intolerance due to non-severe side effects may well be underestimated.2,3

Since differences in the kinetics and metabolism of individual statins exist,3 there is a pharmacological basis for trying a patient who is intolerant of a particular statin on an alternative drug within the same class. Therefore, we set out to establish if patients with intolerance to one or more statin drugs are likely to be intolerant to other drugs in the same class or whether an alternative can usually be found.

Methods

The clinic letters of 1,100 patients who attended the Specialist Lipid Clinic at Hull Royal Infirmary from January 2000 until December 2004 were searched for ‘statin intolerance’ in any part of the text. Intolerance was defined as either subjective symptoms or biochemical abnormalities directly attributable to statins and significant enough to warrant a change or discontinuation of treatment as assessed by a specialist physician. In order to assign causality, these symptoms or signs were required to completely resolve following discontinuation or changing of a particular statin.

Hospital case notes were used to verify and ascertain which statins were used at initial referral and then subsequently during the study period. Patient characteristics, the dose of statins and the nature of symptoms were also recorded, as was success in being able to tolerate an alternative statin.

The order in which particular statins were tried was not fixed but was influenced by the need to reach lipid targets and the nature of the side effect involved. Not all statins were tried in every patient since the decision to continue swapping involved the agreement of the patient.

Results

Forty-four patients (21 male, 23 female; median age 62 years, interquartile range [IQR] 55 to 69 years) were identified who had been referred with intolerance to at least one statin drug (prevalence 4%). At the time of referral, all the selected patients had one or more absolute indications to remain on statin treatment (24 vascular disease, nine significant primary hypercholesterolaemia, six diabetes and 11 familial hypercholesterolaemia).

The problems caused by the initial statin leading to referral were classified broadly into muscle related (e.g. muscle pains, leg pains, muscle tenderness), gastrointestinal (e.g. nausea, indigestion), raised transaminases, central nervous system related (e.g. insomnia, headaches) and others (e.g. alopecia, renal impairment, etc.) (table 1).

Two patients had lipid profiles that were felt to be more appropriately treated with fibrates rather than statins, and two had a high-density lipoprotein (HDL) concentration sufficient not to warrant any lipid-lowering treatment.

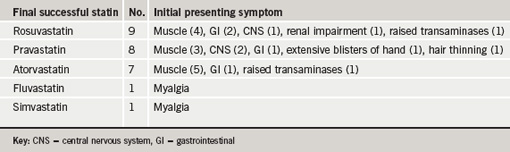

Of those remaining, 26 out of the 40 patients (65%; 11 male, 15 female) were eventually able to tolerate an alternate statin without the initial side effect and remained symptom and complication free in the six-month follow-up (table 2). This required a median of two switches (range one to four) in statin treatment. Fourteen (35%; eight male, six female) were unable to continue statin treatment after a median of 1.5 switches (range one to three), either because of continued intolerance to other agents or a decision not to proceed with trying more alternatives.

Discussion

This is the first study to document the degree of success in switching from a poorly tolerated statin to another of the same class. We found that nearly two thirds of patients (65%) referred to a specialist clinic because of this problem eventually managed to take an alternative statin without side effects. This figure may have been still higher if more patients were willing to persevere with statin switching.

The incidence of statin intolerance in the real-world situation is thought to be between 5% and 10%,2,3 which is higher than that found in most clinical trials. Although the prevalence in our study is 4% of referrals, it is unlikely to be a true prevalence since it involves a selected population attending a specialist lipid clinic. The most common side effects reported are myalgia (prevalence up to 9%),4 non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms, headache, sleep disturbance and minor elevation in transaminases.5 Thus, the side effect profile of patients in this study is similar to that found previously. There were a higher proportion of patients with initial side effects due to simvastatin and atorvastatin, but this is likely to be a consequence of local prescribing patterns rather than an increase in problems with these particular drugs.

The reasons as to why some statins should be tolerated when others are not remain speculative. Certainly, currently prescribed statins can differ in the rate of their metabolism, with atorvastatin and rosuvastatin having particularly long half-lives. Though all statins undergo significant liver metabolism their individual pathways vary. Whereas simvastatin and atorvastatin are mainly metabolised by the cytochrome P450 isoform CYP3A4, fluvastatin utilises the CYP2C9 isoform. Rosuvastatin is not extensively metabolised except for some interaction with the CYP2C9 enzyme and is largely excreted unchanged faecally. Pravastatin is unique since it is metabolised by hepatic pathways independent of the cytochromes and has significant renal excretion. Some statins, such as pravastatin and rosuvastatin, are structurally much more hydrophilic than others so may differ in crossing cell membranes and the blood-brain barrier.5 It is of interest that the two statins that were most frequently tolerated in this study were those which are water soluble, although the number of patients involved were too small to be able to establish these as the drugs of choice in statin-intolerant patients.

In conclusion, this retrospective study supports the trial of alternative statins in patients presenting with initial intolerance due to non-severe adverse effects. Future studies may be able to identify the statin(s) of choice for this growing group of patients.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Vicky Kelly for her help in finding the appropriate clinic letters and retrieving the case notes required for this study. This study was conducted with the audit approval of Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust.

Conflict of interest

ESK has acted as an adviser for all the manufacturers of statins listed in this article.

Key messages

- Intolerance to statins due to non-severe side effects is estimated to affect between 5% and 10% of potential patients

- Very limited, if any, data exist so far in the management of this subgroup of patients

- The pharmacokinetics and metabolism of individual statins vary, providing a pharmacological basis for trial of alternative statins in those intolerant to a particular statin

- Nearly two thirds of the patients who are intolerant to a particular statin are able to tolerate an alternative statin without side effects

References

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Cardiovascular disease – statins. London: NICE, 2006. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA94 [accessed 18th December 2006].

- Simons LA, Levis G, Simons J. Apparent discontinuation rates in patients prescribed lipid-lowering drugs. Med J Aust 1996;164:208–11.

- Moghadasian MH. A safety look at currently available statins. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2002;1:269–74.

- Thompson PD, Clarkson P, Karas RH. Statin-associated myopathy. JAMA 2003;289:1681–90.

- De Angelis G. The influence of statin characteristics on their safety and tolerability. Int J Clin Pract 2004;58:945–55.