Acute heart failure (AHF) is a common cause of hospitalisation, presenting substantial economic and humanistic burden for healthcare systems and patients. This study was designed to capture proxy UK health-related quality of life (HRQoL) data for hospitalised patients with AHF.

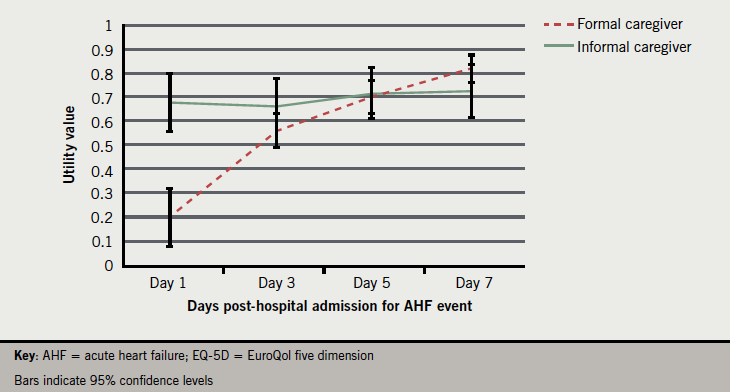

Proxy assessments of HRQoL for patients were obtained from 50 experienced UK cardiac nurses (formal caregivers) and from 50 UK individuals who acted as caregivers for patients who had experienced an AHF event leading to hospitalisation (informal caregivers). Data were collected retrospectively for four time points (days 1, 3, 5 and 7 post-hospital admission for AHF event) using the EQ-5D. Results show a disparity in reported HRQoL at day 1 values between caregiver types (mean single utility index 0.20 vs. 0.68, respectively, p<0.001). By day 7, formal caregivers rated typical patients’ HRQoL as being comparable to informal caregivers’ assessments (0.82 vs. 0.73, respectively, p=0.145).

In conclusion, collection of utility data in severe acute conditions is challenging. This study captures values through the use of proxy assessment. Data suggest that AHF hospitalisation is associated with a significant HRQoL burden and that there exists a need for development of new treatments aimed at improving hospitalisation outcomes.

Introduction

Acute heart failure (AHF) has been defined by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) as the rapid onset of, or change in, symptoms and signs of heart failure, and is a life-threatening condition that requires immediate medical attention.1 These symptoms and signs include shortness of breath at rest or during exertion, fatigue, pulmonary or peripheral fluid retention, a cough, and evidence of an abnormality of the structure or function of the heart at rest.2-4 This change in cardiac function results in an urgent need for therapy, and AHF is among the most common causes of hospitalisation.5 AHF can, therefore, be seen to represent a huge burden on healthcare resources,6 with the need for hospitalisation in order to stabilise the condition of patients being the single largest contributor to the costs of managing AHF.7 The situation is further worsened in that readmission rates are high following discharge; approaching 50% within six months.8

Acute heart failure (AHF) has been defined by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) as the rapid onset of, or change in, symptoms and signs of heart failure, and is a life-threatening condition that requires immediate medical attention.1 These symptoms and signs include shortness of breath at rest or during exertion, fatigue, pulmonary or peripheral fluid retention, a cough, and evidence of an abnormality of the structure or function of the heart at rest.2-4 This change in cardiac function results in an urgent need for therapy, and AHF is among the most common causes of hospitalisation.5 AHF can, therefore, be seen to represent a huge burden on healthcare resources,6 with the need for hospitalisation in order to stabilise the condition of patients being the single largest contributor to the costs of managing AHF.7 The situation is further worsened in that readmission rates are high following discharge; approaching 50% within six months.8

As well as the substantial economic burden on healthcare services, a diagnosis of AHF is associated with a significant health-related quality of life (HRQoL) burden for patients. When making decisions about allocation of healthcare resources, many decision makers consider the impact of the intervention on both costs and health outcomes.9 Health outcomes are commonly aggregated into quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), which is a metric that combines both survival and quality of life. AHF represents a significant challenge to quality of life for patients, due to a combination of the debilitating effects of the condition and the necessity for hospitalisation. Despite the incidence of the condition and the extent of burden experienced there is a paucity of utility data available for AHF, which could be used in economic analyses.

Most HRQoL assessment relies on self-report from patients, but for individuals who are severely or acutely ill this is often not possible for a variety of practical and ethical reasons. Capturing HRQoL information accurately from individuals who are unable or unwilling to complete appropriate instruments, therefore, poses a challenge. One potential approach to overcoming this issue is through the use of proxy assessment. Proxy measures have been successfully used previously in a number of different patient populations including rehabilitation patients10 and individuals with developmental disabilities.11 These studies have demonstrated agreement between self-reported assessments and those of proxies, but other findings suggest that proxy assessment may be subject to bias and measurement error.12

The purpose of the current study was to capture quality of life data for patients in the days immediately following AHF hospitalisation. Given the practical and ethical challenges posed by collecting data directly from acutely ill patients, a proxy assessment approach was employed in which the caregivers of AHF patients were surveyed. In an attempt to address potential sources of bias, proxy assessments were made both by relatives of patients that had experienced recent AHF and by healthcare professionals who regularly manage patients with the condition.

Materials and methods

Participants and methods

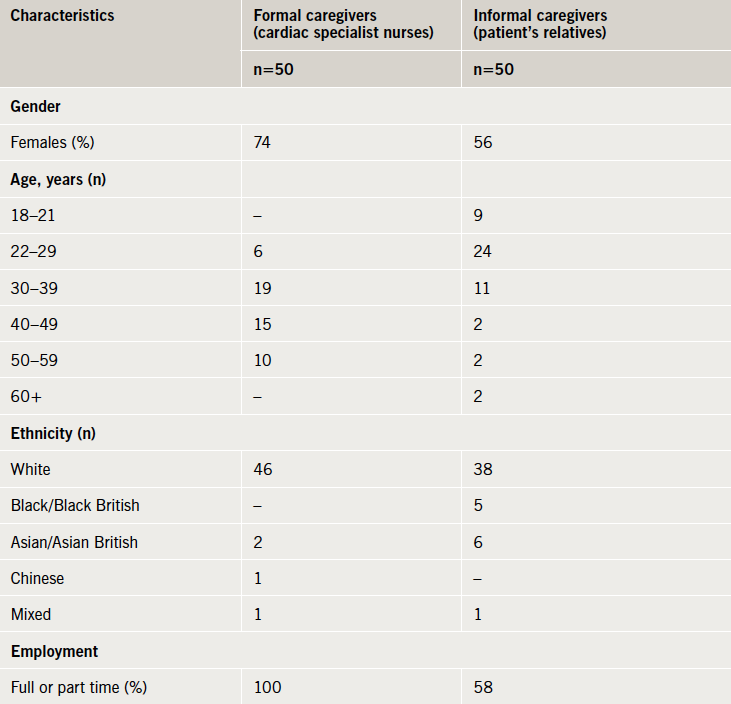

Fifty nurses with a minimum of two years’ experience, who regularly treat cardiac patients (formal caregivers), and 50 close relatives of different patients who had been hospitalised as a result of AHF within the last six months (informal caregivers), were recruited in the UK via a specialist agency. Prior to any data collection taking place, ethical approval was sought for the study protocol from an institutional review board. Potential participants were forwarded a URL for the study website where they were presented with additional information pertaining to the study. Basic sociodemographic data were obtained before proceeding with the assessment exercise.

Participants were asked to provide assessments of the HRQoL of either a ‘typical’ AHF patient (formal caregivers) or the affected relative who was under their care (informal caregivers) at each of four time points (time elapsed since hospital admission = one day, three days, five days, seven days). All assessments were made using the EuroQol five dimension (EQ-5D) instrument.

EQ-5D

The EQ-5D is a widely used generic HRQoL instrument and is the preferred measure of health status for bodies such as the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE).9 It comprises of five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) each with three levels detailing the extent of problems experienced. Subsequent to these evaluations, the EQ-5D contains a 100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS) addressing the individual’s reported current overall health. The EQ-5D has been used previously to assess critically ill individuals in intensive care settings with a variety of different conditions.13,14 Additionally, it has previously demonstrated sensitivity to the HRQoL impact of a number of different heart conditions (including coronary artery bypass and aortic valve surgery, coronary heart disease, and acute coronary syndrome).15-18 Although the instrument was originally designed to be self-completed, many studies have used proxy administration where patient completion may be inappropriate or even impossible.19-21 Calculation of the EQ-5D single index utility value involves the application of preference weights collected from large scale data collection efforts with the general public. Application of the UK weights typically leads to a range of scores from 0 (representing states of health equivalent to being dead), up to a maximum of 1 (representing a state with no health problems). Negative values are possible for states of extremely poor health and represent states rated worse than being dead. The VAS component of the EQ-5D produces scores from 0 (worst imaginable health) to 100 (best imaginable health).

Statistical analysis

Demographic data were summarised using frequency counts and percentages, and independent t-tests were performed to assess differences between caregiver groups at each time point.

Results

Study participants

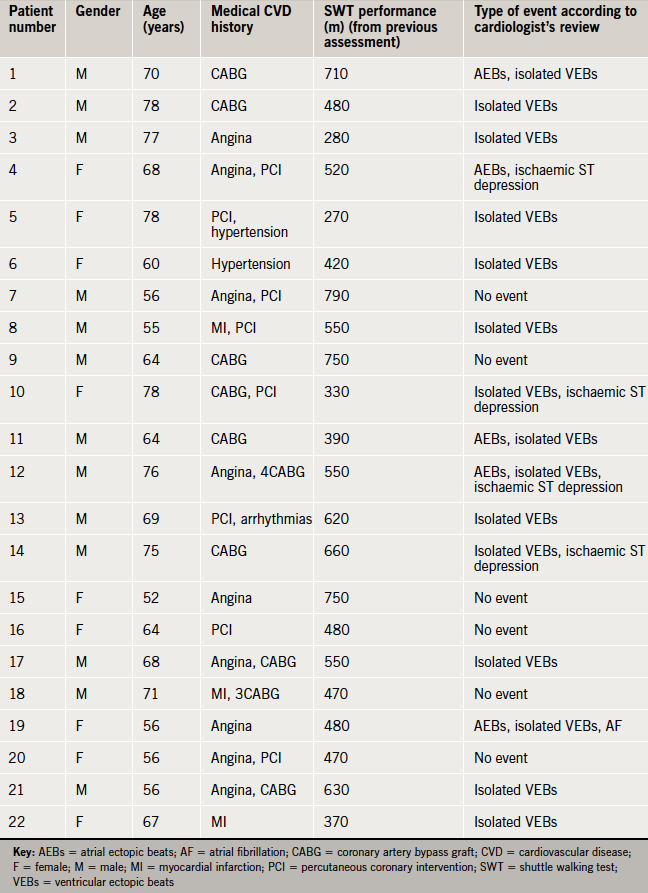

The characteristics of the two caregiver groups are presented in table 1.

Proxy EQ-5D assessments

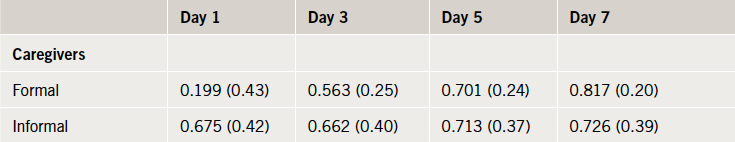

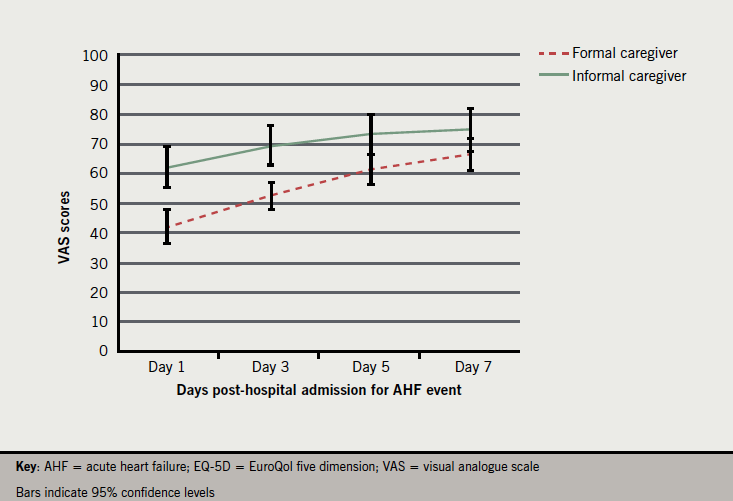

The mean EQ-5D single index utility values calculated for the four time points post-AHF event are reported in table 2. Formal caregiver assessments of HRQoL are significantly lower than those of informal caregivers at day 1 (t[98]=–5.570, p<0.001). Later assessments do not differ significantly between groups and demonstrate a steady improvement in perceived HRQoL over the course of the seven-day period post-AHF event. Figure 1 presents the utility values plotted over time.

acute heart failure event, mean (standard deviation)

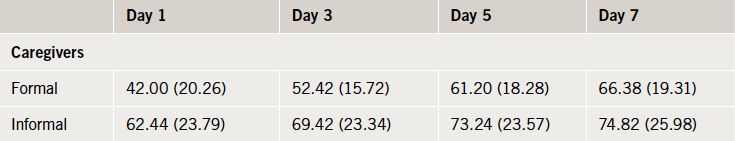

The EQ-5D VAS scores for the four time points post-AHF event are presented in table 3. The disparity in HRQoL assessment at day 1 between the two groups is less marked than seen with the utility values. Formal caregivers assessments of HRQoL based on their experience do, however, remain lower than informal caregivers across all time points and differ significantly at day 1 (t[98]=–4.63, p<0.01), day 3 (t[98]=–4.27, p<0.01) and day 5 (t[98]=–2.85, p<0.01). Visual analogue scale scores for day 7 approximate those for an existing survey of the UK general population (mean 82.5, standard deviation [SD] 17).22 Unlike the trend witnessed with the utility values, the rate of improvement in HRQoL for the two groups is broadly similar (albeit with the formal caregivers suggesting greater overall improvement due to lower baseline values). Figure 2 presents VAS scores plotted over time.

event, mean (standard deviation)

Discussion

This study aimed to assess HRQoL for patients who have been hospitalised as a result of AHF. Health utilities were captured via proxy administration of the EQ-5D instrument with both formal and informal caregivers. The findings suggest that AHF hospitalisation is associated with very poor quality of life, at least in the short term. Over the course of the seven days following hospitalisation, significant improvement occurs as evidenced by the increase in reported utility values. The results also demonstrate some disparity exists as to the average extent of problems experienced by patients as judged by the different caregiver groups. The utility values for the formal and informal caregivers deviate greatly at day 1 after the AHF event but, as expected, both suggest that patients experience substantial problems related to ill health and hospitalisation.

Previous studies have found the EQ-5D instrument can be valid when administered by proxy.23-24 The decision to use two different sources of proxy values in the study was an attempt to avoid introducing systematic bias into the results. It is likely that both the formal and informal caregiver group assessments are influenced by a number of factors unique to their relationship with patients. Formal caregiver assessments of a ‘typical’ AHF patient suggest that HRQoL is more detrimentally affected by event-related hospitalisation. This may be a product of a more ‘functional capacity’ based approach to evaluating health. Given the extremely debilitating immediate impact of an AHF event this could lead to reports of greatly diminished HRQoL. In contrast, informal caregiver assessments of relatives HRQoL suggest that the deterioration is somewhat less pronounced. It is likely that these particular assessments are informed by a more intimate knowledge of the pre-event baseline health status of patients and reflect a ‘relative change’ based evaluation approach. Although the assessment exercises conducted by the raters are essentially different in terms of their focus, it is difficult to argue that either assessment is objectively superior when looking solely at data collected using the EQ-5D. As the instrument was designed specifically for use by members of the general public with no formal medical training this should not disadvantage informal caregivers in making valid assessments. Future work looking at the level of agreement between retrospective patient assessments of HRQoL and those made by proxies may give a clearer indication of which values correspond more closely. Of course, such retrospective assessments are themselves subject to confounds in the form of recall biases.

The study has some important limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. No assessment was captured directly from any patient, which introduces concerns over the validity of the values obtained. However, there are clearly a number of logistical and ethical issues, such as the difficulty in obtaining informed consent from severely ill patients, which make prospective data collection challenging. Retrospective data collection presents one possible alternative method for obtaining suitable HRQoL data. Such an approach could be nonetheless affected by a selection bias with only those who survived (and perhaps, therefore, those with the least severe events or best outcomes) being capable of providing data. It is possible that this selection bias may have influenced the current study, with the caregivers who participated being relatives of patients who are recovering or have recovered from the AHF event (although we do not have sufficient data to verify this assumption). Informal caregivers may have been assessing a less severely affected group of patients than formal caregivers, and this could, therefore, at least partly explain differences in the HRQoL ratings from the two groups. The retrospective assessment approach taken in this study may also have led to recall bias. Given the nature of their occupation, formal caregivers are more likely to have had recent and frequent experience of patients in the immediate post-AHF state. In practical terms, this problem is difficult to avoid when employing such a methodology. We have attempted to limit the potential for this to occur by including an inclusion criteria that the patients under the informal caregivers care had to have experienced the AHF event a maximum of six months previously (with the majority doing so within a three-month period). Although this shorter period of time should facilitate more accurate recall, the relatively small window of time between each study time point (day 1, 3, 5 and 7 post-AHF event) may serve to blur distinctions in the patient’s quality of life at these intervals. This may be reflected in the fact that the range of utility values for the informal carer group is narrower than that of the formal caregivers. All of these potential sources of bias were recognised when the study was designed, which led us to make the decision to include data collection from two independent groups. Despite these limitations we believe that the study has provided some insight into the HRQoL effects of AHF hospitalisation as viewed by different caregiver groups. Interestingly, a recent draft of the NICE guidelines for health technology assessment has proposed the use of caregiver derived utility values in preference to those provided by healthcare professionals when collecting HRQoL data.25

The study supports previous research suggesting that there is a marked decline in HRQoL associated with hospitalisation as a result of experiencing an AHF event. Recent research has suggested that there is significant variation in prescribing practices, which may have led to suboptimal outcomes for many patients.26-27 Improved pharmacological management of AHF to reduce the incidence of hospitalisation and length of stay, could confer substantial benefits for patients and healthcare systems.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Georgia Tarnesby, employed by Novartis Pharma, for reviewing and providing comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Postfach, CH-4002 Basel, Switzerland.

Conflict of interest

SHO and PL are employed by Novartis Pharma AG. Oxford Outcomes were paid a fixed fee to design and conduct this study by Novartis Pharma AG.

Key messages

- Acute heart failure (AHF) is a common cause of hospitalisation, presenting a substantial burden for healthcare systems, as well as patients. This study was designed to capture proxy UK health-related quality of life (HRQoL) data for hospitalised patients with AHF

- This study demonstrates the feasibility of capturing HRQoL data for acutely unwell patients, perhaps unable or unwilling to self-report such issues

- Results show a disparity in reported HRQoL at day 1 values between caregiver types; however, by day 7, formal caregivers rated typical patients’ HRQoL as being comparable to informal caregivers ratings

- Findings suggest AHF hospitalisation is associated with notable HRQoL burden and that improved pharmacological management could lead to significant benefits for both patients and healthcare systems

References

- ESC (European Society of Cardiology) Task Force. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1787–847. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs104

- Dickstein K, Cohen-Solal A, Filippatos G et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008. The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2008;10:933–89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.08.005

- Goldberg R, Spencer F, Szklo-Coxe M et al. Symptom presentation in patients hospitalized with acute heart failure. Clin Cardiol 2010;33:e73–e80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/clc.20627

- Gheorghiade M, Filippatos G, De Luca L, Burnett J. Congestion in acute heart failure syndromes: an essential target of evaluation and treatment. Am J Med 2006;119(suppl 1):S3–S10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.09.011

- Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010;121:e45–e215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667

- Ross EA, Bellamy FB, Hawig S, Kazory A. Ultrafiltration for acute decompensated heart failure: cost, reimbursement and financial impact. Clin Cardiol 2011;34:273–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/clc.20913

- O’Connell JB. The economic burden of heart failure. Clin Cardiol 2000;23(suppl 3):III6–III10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/clc.4960231503

- Krumholz H, Chen Y, Wang Y et al. Predictors of readmission among elderly survivors of admission with heart failure. Am Heart J 2000;139:72–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8703(00)90311-9

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Guide to the methods of technology appraisal. London: NICE, June 2008. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/niceMedia/pdf/TAP_Methods.pdf

- McPhail S, Beller E, Haines T. Two perspectives of proxy reporting of health-related quality of life using the Euroqol-5D, An investigation of agreement. Med Care 2008;46:1140–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817d69a6

- Schmidt S, Power M, Green A et al. Self and proxy rating of quality of life in adults with intellectual disabilities: results from the DISQOL study. Res Dev Disabil 2010;31:1015–26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2010.04.013

- Tamim H, McCusker J, Dendukuri N. Proxy reporting of quality of life using the EQ-5D. Med Care 2002;40:1186–95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200212000-00006

- Badia X, Diaz-Prieto A, Rue M, Patrick DL. Measuring health and health state preference among critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 1996;22:1379–84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01709554

- Cristina G, Armando TP, Altamiro CP. Quality of life after intensive care – evaluation with EQ-5D questionnaire. Intensive Care Med 2002;28:898–907. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00134-002-1345-z

- Ellis JJ, Eagle KA, Kline-Rogers EM, Erickson SR. Validation of the EQ-5D in patients with a history of acute coronary syndrome. Curr Med Res Opin 2005;21:1209–16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1185/030079905X56349

- Kahyaoglu Süt H, Unsar S. Is EQ-5D a valid quality of life instrument in patients with acute coronary syndrome? Anadolu Kardiyol Derg 2011;11:156–62. http://dx.doi.org/10.5152/akd.2011.037

- Markou AL, de Jager MJ, Noyez L. The impact of coronary artery disease on the quality of life of patients undergoing aortic valve replacement. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2011;13:128–32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1510/icvts.2011.269209

- Xie J, We EQ, Zheng ZJ, Sullivan PW, Zhan L, Labarthe DR. Patient-reported health status in coronary heart disease in the United States: age, sex, racial and ethnic differences. Circulation 2008;118:491–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.752006

- Hung MC, Yan YH, Fan PS et al. Measurement of quality of life using EQ-5D in patients on prolonged mechanical ventilation: comparison of patients, family caregivers, and nurses. Qual Life Res 2010;19:721–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9629-1

- Matza LS, Secnik K, Mannix S, Sallee FR. Parent-proxy EQ-5D ratings of children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in the US and the UK. Pharmacoeconomics 2005;23:777–90. http://dx.doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200523080-00004

- Wolfs CA, Dirksen CD, Kessels A, Willems DC, Verhey FR, Severens JL. Performance of the EQ-5D and the EQ-5D+C in elderly patients with cognitive impairments. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2007;14:33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-33

- Kind P, Dolan P, Gudex C et al. Variations in population health status: results from a United Kingdom national questionnaire survey. BMJ 1998;316:736–41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.316.7133.736

- Klaassen RJ, Barr RD, Hughes J, Rogers P, Anderson R, Grundy P. Nurses provide valuable proxy assessment of health-related quality of life of children with Hodgkin disease. Cancer 2010;116:1602–07. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24888

- Pickard S, Jeffrey A, Johnson A, Feeny DH, Shuaib A, Carriere KC. Agreement between patient and proxy assessments of health-related quality of life after stroke using the EQ-5D and Health Utilities Index. Stroke 2004;35:607–12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000110984.91157.BD

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Guide to the methods of technology appraisal, third edition draft for consultation. London: NICE, 2012. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/media/CB1/43GuideToMethodsOfTechnologyAppraisal2012.pdf

- Fonarow GC, Yancy CW, Albert NM et al. Heart failure care in the outpatient cardiology practice setting. Circ Heart Fail 2008;1:98–106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.772228

- Albert NM, Yancy CW, Liang Li et al. Use of aldosterone antagonists in heart failure. JAMA 2009;302:1658–65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1493