MVP may or may not result in mitral regurgitation and is diagnosed using echocardiography based upon movement of a section of the leaflet of ≥2 mm above the mitral annulus. The prevalence of this condition using such criteria has been estimated at 2–3% of the population.

Most commonly MVP occurs as a primary condition but has also been associated with connective tissue disorders, such as Marfan’s and Ehlers Danlos syndrome type IV (see figure 7). The most prominent finding in primary MVP is the myxomatous expansion of the spongiosa layer of the valve driven by an increased quantity of acid mucopolysaccharides. The leaflets appear thickened (≥5 mm in diastasis) and in severe cases become grossly abnormal, redundant and prolapsed. This myxomatous proliferation can also affect the annulus (resulting in its dilatation) and the chordae tendinae. Degeneration of collagen within the latter causes the chordae to thin and elongate, further contributing to valve prolapse and predisposing the patient to chordal rupture.

Fibroelastic deficiency is more common in the elderly.

Rheumatic heart disease

Rheumatic fever occurs in children aged 5–15 years from a type II immune response to group A beta-haemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis. The response occurs after one to five weeks and is caused by molecular mimicry between streptococcal M protein and human myosin and between group A carbohydrate in the streptococcus and valve tissue.

This results in inflammatory damage within the myocardium, joints, brain and skin to collagen fibrils and the ground substance of connective tissue.

Its major importance relates to the progressive heart valve disease that continues long after resolution of the initial infection. This can affect any of the four valves although in the vast majority of cases it affects the mitral valve alone or in combination with other valves. It is driven by repeated inflammatory episodes and the fibrotic healing response that ensues. Characteristically valve leaflets fuse at their edges resulting in valve stenosis. The chordae are also frequently involved, and fusion, shortening and thickening of these structures can result in mal-apposition of the valve leaflets and regurgitation. A mixed picture of valve disease is therefore often identified.

Only a small proportion of the population (about 3%) develop the abnormal rheumatic immune response to group A streptococcal infection but, interestingly, these patients are then at significantly increased risk of repeated bouts of rheumatic fever with subsequent streptococcal exposure (in about 50%). This has been linked to different human leukocyte haplotypes and has prompted the American Heart Association to recommend antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with known rheumatic heart disease, especially in childhood and early adulthood.

Functional valve disease

Mitral regurgitation

Valve dysfunction can occur in the context of a structurally normal valve. Functional mitral regurgitation occurs as a result of left ventricular dysfunction causing altered stresses on the mitral valve apparatus with restriction of the leaflets. There may also be dilatation of the annulus.

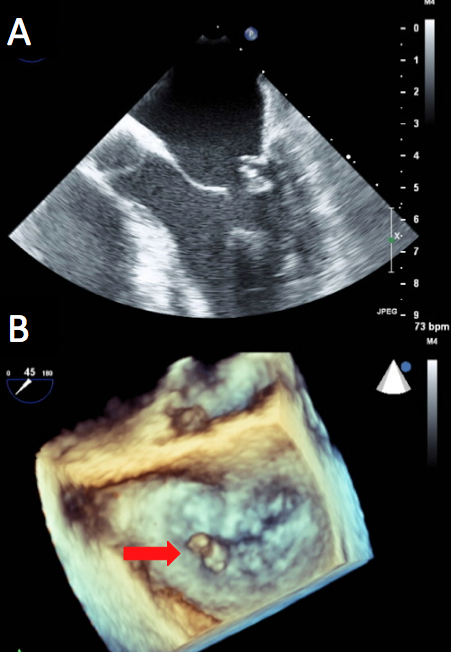

Leaflet restriction may be ‘asymmetric’ when it affects predominantly the posterior leaflet and causes a jet of regurgitation directed posteriorly. The papillary muscles are perfused by the coronary vasculature and are therefore susceptible to the effects of coronary ischaemia. This can result in reversible restriction of the posterior mitral leaflet. At its most extreme, papillary muscle rupture (see figures 8A and 8B) can result in acute severe mitral regurgitation as a life-threatening complication two to three days following myocardial infarction. This is most commonly associated with an infero-posterior myocardial infarction.

Restriction may also be ‘symmetric’ which results from more generalised left ventricular dysfunction and causes a central jet of mitral regurgitation.