Aortic regurgitation

Aortic regurgitation is frequently observed as a consequence of aortic root dilatation, due to annular dilatation and failure of coaptation. Indeed, this is now a more common cause of regurgitation than primary valve disease amongst patients referred for aortic valve replacement. Aortic root dilatation can be the result of long-standing hypertension, bicuspid valve disease, Marfan’s syndrome, syphilis, as well as a range of other connective tissue disorders.

Endocarditis

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a microbial infection of the endothelial surface of the heart to which patients with pre-existent valve disease are predisposed.6 Patients with an intact cardiac endothelium are relatively protected but the endothelial damage associated with structural and valvular heart disease encourages a thrombotic response which is much more receptive to bacterial colonisation. However, a half of cases occur in patients without known pre-existing valvular heart disease. Ultimately the development of infective endocarditis is believed to be a multi-stage process requiring endothelial damage, the formation of platelet-fibrin deposits called non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE), and the colonisation of these deposits at the time of bacteraemia.

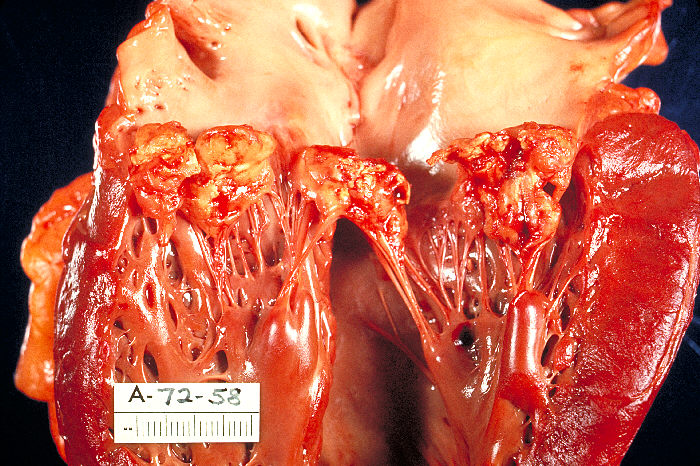

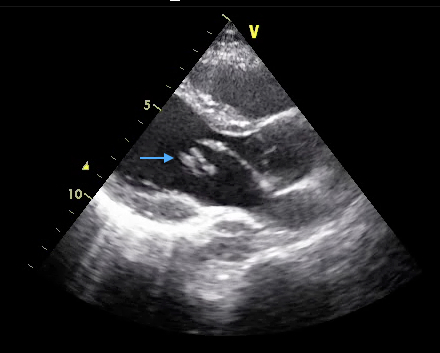

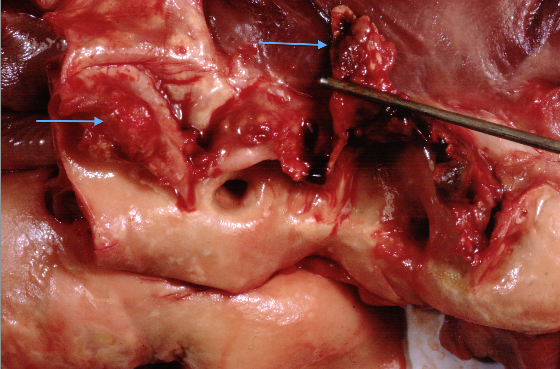

Bacteraemia occurs frequently, following events that traumatise the oral, genitourinary or gastrointestinal mucosa. The critical step in the development of IE appears to be the adherence of these organisms to the NBTE. This is mediated by the interaction between a range of bacterial surface proteins and matrix components of NBTE (e.g. fibronectin) and results in the formation of vegetations. These lesions are characteristic of IE and consist of an amorphous mass of platelets, fibrin, inflammatory cells and microorganisms. Vegetations grow with time, driven by the persistence and multiplication of the invading microorganism, which themselves encourage further platelet and fibrin aggregation (see figures 9 and 10). Ultimately this can cause destruction of valve tissue, perforation, chordal rupture or combinations of these leading to severe regurgitation and ultimately heart failure. Fragmentation of the vegetations causes systemic embolisation including stroke. Furthermore, with progressive microorganism replication, bacteria are shed into the blood stream encouraging sepsis and immune-complex mediated damage. Local tissue damage and sepsis can lead to abscess formation, fistulae and conductive system damage.

Over three quarters of infections are caused by streptococcal and staphylococcal organisms, with the latter particularly prevalent amongst intravenous drug users. Streptococcus bovis endocarditis may be associated with lower gastrointestinal pathology both benign and malignant, whilst fungal infections should be considered in those with compromised immune systems. The latter frequently result in large vegetations that are also observed with the HACEK (Haemophilus, Actinobacillus, Cardiobacterium, Eikenella, and Kingella species) group of organisms (see figure 10). Culture negative endocarditis occurs in 5–10% of cases and is most commonly due to the administration of antibiotics prior to blood culture sampling but may also be related to infection with Candida, Aspergillus, Q-fever and Bartonella. Recent guidelines have moved away from antibiotic prophylaxis of those with pre-existent valve disease because of the lack or randomised control data for the efficacy of this approach. The National Institute for Heath and Care Excellence (NICE) recently reviewed this guidance due to reports of increasing incidence of IE however the recommendations originally published in 2008 were not altered. Of note both the AHA and ESC guidelines still recommend antibiotic prophylaxis for patients with replacement heart valves or prior IE.