ESC guidelines advise that beta-blockers or negatively chronotropic calcium channel blockers (such as diltiazem or verapamil) can improve exercise tolerance.22 These agents should prolong diastole and reduce the transmitral gradient in MS, although clinical trial data are scant and show mixed results with regards to symptomatic improvement.28–34

A recent open label crossover study randomised 50 patients with mild to moderate MS (all in sinus rhythm) to either atenolol or ivabradine (a negatively chronotropic If channel blocker with minimal effects on myocardial contractility).35 Ivabradine (see figure 7) was found to significantly improve exertional capacity.

AF is very common in patients with significant MS. A rhythm control strategy without definitive interventional treatment of the underlying valve abnormality (balloon mitral valvuloplasty or surgery) is rarely successful.

Right-sided valve disease

Evidence for both disease-modifying and supportive treatments is limited for diseases of the tricuspid and pulmonary valves. Diuretics are indicated to reduce preload in patients with significant congestion and treatment of the underlying cause in cases of functional tricuspid regurgitation (for example, correction of volume loading of a dilated right ventricle) may successfully treat the valve abnormality. Patients with significant right ventricular impairment may benefit from ACEIs, ARBs, and aldosterone antagonists, though there is no evidence to confirm this approach.

Anticoagulation

In general, the risk-benefit analyses of anticoagulation in patients with non-valvular AF are applicable to patients with both AF and VHD – with the notable exception of those with MS or metallic prosthetic valves (covered in detail in module 7: anti-thrombotic therapy for valvular heart disease). For example, the Cardiovascular Health Study did not show an increased risk of stroke in patients with AS compared to those with normal aortic valves once other risk factors were taken into account.36

Pivotal trials leading to the licensing of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) have provided valuable information on risk of stroke and bleeding. Although the exact definition of “non-valvular” AF varied between trials, most trials only excluded patients with MS or a prosthetic heart valve.37.For example, over a quarter of participants in the Apixaban for the Prevention of Strokes in Subjects with Atrial Fibrillation (ARISTOTLE) trial comparing apixaban to warfarin had at least moderate VHD.38 In these trials, participants with VHD tended to be older with higher risk of embolism and bleeding, but derived similar benefits from NOACs as participants without VHD (although a higher bleeding risk was seen with rivaroxaban).39,40 Current ESC VHD guidelines recommend anticoagulation with warfarin (target international normalised ratio (INR) 2.0–3.0) in all patients with AF and VHD who do not have a significant contraindication or bleeding risk,22 while more recent recommendations from the European Heart Rhythm Association suggest that treatment with NOACs is also reasonable for these patients.39

MS confers a substantially higher risk of systemic thromboembolism. Anticoagulation is recommended for patients with MS without documented AF but with a history of systemic embolism or left atrial thrombus. Anticoagulation should be considered if the left atrium is significantly enlarged (2D dimension >50 mm or left atrial volume index >60 ml/m2), or if there is dense spontaneous echo contrast on transoesophageal echocardiography.22

Endocarditis prophylaxis

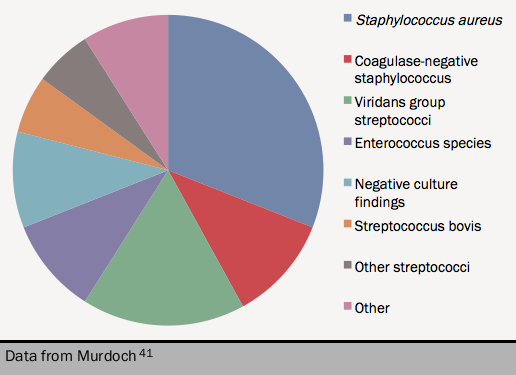

Recommendations for endocarditis prophylaxis have changed dramatically over the past decade. International guidelines have restricted the indications for prophylaxis in the majority of situations, citing the frequent bacteraemia seen after routine tooth brushing, the lack of evidence of efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis, the rarity of endocarditis after dental procedures, the risk of encouraging antibiotic resistance and the potential (albeit rare) risk of anaphylactic reaction to an antibiotic (see figure 841).