The sensitivity for detecting vegetations with transthoracic echocardiography using modern machines is about 75% for native valve endocarditis. Transthoracic echocardiography may be more sensitive than transoesophageal echocardiography for anterior aortic abscesses and for the tricuspid valve. However, possible indications for transoesophageal echocardiography include:

- Likely prosthetic valve endocarditis

- Infection of a cardiac implanted device (vegetation in 20% on TTE and 71% on TOE)21

- Normal transthoracic study or non-diagnostic study and continuing clinical suspicion of endocarditis

- Suspicion of an abscess (e.g. long PR interval) or abnormal transthoracic study

- Aortic valve endocarditis (because of the high incidence of abscess, large vegetations)

Guidelines9 recommend a transoesophageal study in all cases other than those with a low clinical suspicion of endocarditis with a normal transthoracic study. However in individual cases this may not be necessary if the transthoracic study has already given the diagnosis and the transoesophageal study will not change management (e.g. the decision for surgery already made). The two approaches are often complementary with TOE giving better detection of abscesses and assessment of vegetation size and mobility while TTE gives better assessment of the haemodynamic complications and LV function.

Transthoracic echocardiography is not used for monitoring but should be performed:

- At admission

- If there is a clinical change

- Predischarge if inpatient surgery not performed

- As an outpatient usually at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months

- After an intervention

– Valve replacement or repair

– Removal of an implantable cardiac electronic device (to check for pericardial effusion and TR)?

Other imaging techniques

CT may detect vegetations on heavily calcified valves22 and may detect abscesses missed by TOE. Both CT and CMR are useful if aortic root pathology is not well seen on TTE and if TOE is not feasible, or if there is complex pathology (e.g. false aneurysms or complex abscesses). Combined positron emission tomography and computed tomography (PET-CT) can be useful for diagnosing infection of implantable electrical devices23 and replacement heart valves more than three months after implantation.

Special situations

Prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE)

A replacement valve has approximately 100 times the risk of developing IE than the general population. The risk is 4% in the first one year after implantation then 0.3-1.2% per year after this.9,24 The mortality is higher than for native IE, up to 65% if there is uncontrolled sepsis.25

The response to antimicrobials is less good than for native IE but it is possible to cure a proportion of cases without redo surgery in about 40% cases. Cure is more likely if infection is caused by oral streptococci compared to S. aureus.

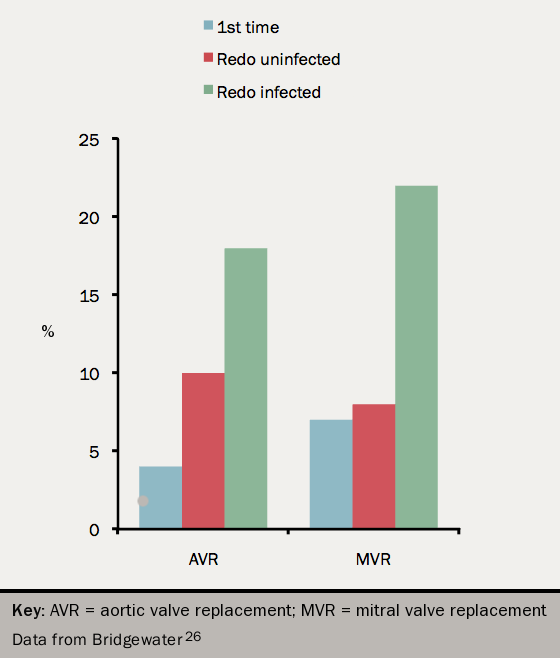

The surgical mortality and long-term outcome are worse for PVE than NVE (see figure 726).

Device related IE

Implantable cardiac electronic devices (e.g. pacemakers, implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD)) can become infected. The leads may become infected and valves may become involved. Device removal is the most effective management, combined with antimicrobial therapy.27

IVDU-associated IE

This is commonly right-sided and usually responds to antimicrobials without the need for surgery.

Surgery is only occasionally needed with very high risk features: ongoing bacteraemia despite appropriate antimicrobial therapy, difficult to eradicate organisms, persistent large (>20 mm) tricuspid valve vegetations after recurrent pulmonary emboli, or right heart failure due to severe TR refractory to medical therapy.1

To avoid relapse, enrolment in a drug rehabilitation programme is a vital part of treatment of the index condition. The relapse rate is up to 40%.

Culture negative endocarditis

Ensure that cultures have been incubated sufficiently long for slow-growing organisms including the HACEK organisms.

Negative cultures occur in 5–20% of cases. The most common cause, in about one half, is prior antimicrobial therapy. Other causes are:

- Candida

- Coxiella

- Bartonella

- Brucella (in regions like the Mediterranean where Brucella is found)

- SLE

- Malignancy

Discuss management with an infection specialist.

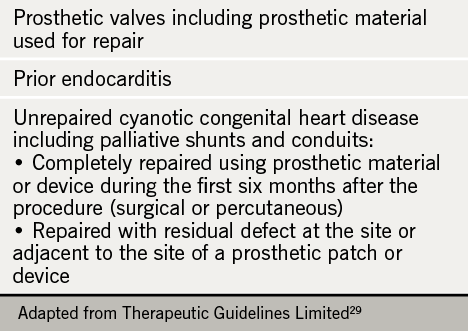

Preventing endocarditis

Over recent years the recommended indications for antimicrobial prophylaxis have reduced. Prophylaxis is still recommended by many national or international guidelines9,28,29 for high-risk patients (see table 5) having high-risk dental procedures (extractions, scaling, gingival surgery, endodontic treatment). US guidelines28 add heart transplant patients with acquired valve disease and Australian guidelines29 also include rheumatic disease in aboriginal people.

In England and Wales, however, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)30 does not recommend antimicrobial prophylaxis before any dental procedures even in high-risk patients. There is some suggestion2 that this has resulted in an increase in the rate of increase of endocarditis but this is disputed29. Agreement with NICE recommendations is variable31

All guidelines agree that dental hygiene and general measures to prevent infection (see table 6) are important.

Table 6. Non-specific prevention measures to be followed in high-risk and intermediate-risk patients followed in high-risk and intermediate-risk patients

This table can be viewed as table 4 in Habib9

Key points

- A low index of suspicion is required for diagnosis.

- Blood cultures and echocardiography are key investigations.

- A specialist endocarditis team should manage or supervise the management.

- Appropriate antimicrobial therapy is critical but involve a surgeon early unless clearly low risk.

- Failure of appropriate antimicrobial therapy (correct agent and dose) usually requires surgery rather than a second antibiotic regimen.

- Do not delay surgery for dental treatment or for investigation of the GI tract.

close window and return to take test

References

1. Habib G, Hoen B, Tornos P, et al. Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of infective endocarditis (new version 2009): The Task Force on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2009;30:2369–413. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehp285

2. Dayer MJ, Jones S, Prendergast B, Baddour LM, Lockhart PB, Thornhill MH. Incidence of infective endocarditis in England, 2000–13: a secular trend, interrupted time-series analysis. Lancet 2014;385:1219–28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62007-9

3. Pant S, Patel NJ, Deshmukh A et al. Trends in infective endocarditis incidence, microbiology and valve replacement in the United States from 2000-2011. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:2070–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.518

4. Correa de Sa DD, Tleyjeh IM, Anavekar NS, et al. Epidemiological trends of infective endocarditis: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:422–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2009.0585

5. Verheugt CL, Uiterwaal CSPM, van der Velde ET, et al. Turning 18 with congenital heart disease: prediction of infective endocarditis based on a large population. Eur Heart J 2011;32:1926–34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehq485

6. Murdoch DR, Corey R, Hoen B, et al. Clinical presentation, etiology, and outcome of infective endocarditis in the 21st century: the International Collaboration on Endocarditis Prospective Cohort Study. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:463–73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2008.603

7. Kiefer T, Park L, Tribouilloy C, et al. Association between valvular surgery and mortality among patients with infective endocarditis complicated by heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;306:2239–47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1701

8. Li JS, Sexton DJ, Mick N, et al. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis 2000;30:633–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/313753

9. Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis. Eur Heart J (epublication August 29th 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319

10. Chambers J, Ray S, Prendergast B, et al. Endocarditis services: recommendations from the British Heart Valve Society working group on improving quality in the delivery of care for patients with heart valve disease. Heart 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2013-303754

11. Chambers J, Sandoe J, Ray S, et al. The infective endocarditis team: recommendations from an international working group. Heart 2014;100:524–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304354

12. Tornos P, Iung B, Permanyer-Miralda G, et al. Infective endocarditis in Europe: lessons from the Euro heart survey. Heart 2005;91:571–5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2003.032128

13. Botelho-Nevers E, Thuny F, Casalta JP, et al. Dramatic reduction in infective endocarditis-related mortality with a management-based approach. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1290–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.192

14. Delahaye F, Rial M-O, de Gevigney G, Echochard R, Delaye J. A critical appraisal of the quality of the management of infective endocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33:788–93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(98)00624-X

15. Gould FK, Denning DW, Elliott TSJ, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and antibiotic treatment of endocarditis in adults: a report of the Working Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012;67:269–89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkr450

16. Lalani T, Cabell CH, Benjamin DK, et al. Analysis of the impact of early surgery on in-hospital mortality of native valve endocarditis: use of propensity score and instrumental variable methods to adjust for treatment-selection bias. Circulation 2010;121:1005–13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.864488

17. Kang D-H, Kim Y-J, Kim S-H, et al. Early surgery versus conventional treatment for infective endocarditis. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2466–73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1112843

18. Welton D, Young JB, Gentry WO, Raizner AE, Alexander JK, Chahine RA, Miller RR. Recurrent infective endocarditis. Am J Med 1979;66:932. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(79)90447-9

19. Thangaroopan M, Choy JB. Is transesophageal echocardiography overused in the diagnosis of infective endocarditis? Am J Cardiol 2005;95:295–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.09.022

20. Vieira MLC, Grinberg M, Pomerantzeff PMA, Andrade JL, Mansur AJ. Repeated echocardiographic examinations of patients with suspected infective endocarditis. Heart 2004;90:1020–4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2003.025585

21. Dumonta E , Camusb C, Victora F, et al. Suspected pacemaker or defibrillator transvenous lead infection: prospective assessment of a TEE-guided therapeutic strategy. Euro Heart J 2003;24:1779–87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ehj.2003.07.006

22. Fagman E, Perrotta S, Bech-Hanssen O, et al. ECG-gated computed tomography: a new role for patients with suspected aortic prosthetic valve endocarditis. Eur Radiol 2012;22:2407–14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00330-012-2491-5

23. Sarrazin JF, Philippon F, Tessier M, et al. Usefulness of fluorine-18 positron emission tomography/computed tomography for identification of cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:1616–25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.059

24. Grunkemeier GL, Li H-H, Naftel DC, Starr A, Rahimtoola SH. Long-term performance of heart valve prostheses. Curr Probl Cardiol 2000;25:73–156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/cd.2000.v25.a103682

25. Wang A, Athan E, Pappas PA, et al. Contemporary clinical profile and outcome of prosthetic valve endocarditis. J Am Med Assoc 2007;297:1354–61. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.12.1354

26. Bridgewater B, Kinsman R, Walton P, Keogh B. Demonstrating quality: The sixth National Adult Cardiac Surgery database report. Dendrite Clinical Systems Ltd. 2009. ISBN: 1-903968-23-2 http://www.scts.org/_userfiles/resources/SixthNACSDreport2008withcovers.pdf

27. Sandoe J, Barlow G, Chambers JB, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis, prevention and management of Implantable Cardiac Electronic Device Infection. Report of a joint working party project on behalf of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (BSAC, host organisation), British Heart Rhythm Association (BHRA), British Cardiovascular Society (BCS), British Heart Valve Society (BHVS) and British Society for Echocardiography (BSE). Lancet 2015;385:225–6. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62249-2

28. ACC/AHA guideline update on valvular heart disease: focused update on infective endocarditis. Circulation 2008;118: 887–96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.008

29. Infective Endocarditis Prophylaxis Expert Group. Prevention of endocarditis. 2008 update from Therapeutic guidelines: antibiotic version 13, and Therapeutic guidelines: oral and dental version 1. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited, 2008 (http://www.csanz.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Prevention_of_Endocarditis_2008.pdf)

30. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Prophylaxis against infective endocarditis. Antimicrobial prophylaxis against infective endocarditis in adults and children undergoing interventional procedures. CG64. London: NICE, 2008. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg64/evidence

31. Dayer MJ, Chambers JB, Prendergast B, Sandoe JAT, Thornhill MH. NICE guidance on antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent infective endocarditis: a survey of clinicians’ attitudes. QJM 2013;106: 237–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcs235

close window and return to take test

All rights reserved. No part of this programme may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers, Medinews (Cardiology) Limited.

It shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent.

Medical knowledge is constantly changing. As new information becomes available, changes in treatment, procedures, equipment and the use of drugs becomes necessary. The editors/authors/contributors and the publishers have taken care to ensure that the information given in this text is accurate and up to date. Readers are strongly advised to confirm that the information, especially with regard to drug usage, complies with the latest legislation and standards of practice.

Healthcare professionals should consult up-to-date Prescribing Information and the full Summary of Product Characteristics available from the manufacturers before prescribing any product. Medinews (Cardiology) Limited cannot accept responsibility for any errors in prescribing which may occur.