A. Menarini Farmaceutica Internazionale SRL has provided an educational grant for the production of this e-learning programme and has had no editorial control or input. The views and content expressed within this programme are solely those of the authors.

PP-CA-UK-0147 Date of preparation: March 2020

What is angina?

William Heberden in 1772 was one of the first to describe angina pectoris (figure 1). He described, “a disorder of the breast, marked with strong peculiar symptoms… the sense of strangling.” He keenly noted that it was, “not extremely rare… those affected with it, are seized while they are walking… but the moment they stand still, all this uneasiness vanishes”.

His observations reign true today, with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on chest pain of recent onset1 defining typical stable angina as the presence of:

- constricting discomfort in the front of the chest, or in the neck, shoulders, jaw or arms

- precipitated by physical exertion

- relieved by rest or glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) within about five minutes.

What causes angina?

Angina is caused when required oxygen demand of the myocardium cannot be met. The most common cause for this is atherosclerotic lesions within the coronary arteries leading to flow limitation. Angina is not specific to atherosclerosis and the symptoms can also be caused by: coronary spasm, aortic valve disease, microvascular coronary dysfunction, oesophageal spasm and reflux, and anaemia.

Key facts

- Worldwide and in Europe, ischaemic heart disease (IHD) also referred to as coronary heart disease (CHD) remains the leading cause of death.2

- An estimated 2.3 million people are living with CHD in the UK (BHF 2019).

- In England and Wales in 2018, dementia and Alzheimer disease is now the leading cause of death (12.8%) with IHD second (10.8%).3

- Cardiovascular disease (CVD) had been the leading cause of death in the UK since 1961 until being overtaken by cancer (all sub-types) in 2012.4

- CVD costs the UK economy an estimated £19 billion per year through premature death, disability and informal costs.5

Prevalence

The prevalence of stable angina is difficult to assess as it is a diagnosis based upon history and therefore requires clinical judgement. The prevalence of stable angina increases with age in both sexes.6 Women aged 45–64 years have a prevalence of 5–7%, whilst men in the same age range have a prevalence of 4–7%. This increases to a prevalence of 10–12% in women aged 65–84 years and 12–14% in similarly aged men.

The patient-reported Health Survey for England,7 which asks individuals whether they have ever been given a diagnosis of angina by a health professional has a similar prevalence with angina having a 3% prevalence in all adults, and the highest burden in those aged over 75 years where the prevalence is 11%. Within the average GP practice in the UK of 8,000 patients, around 300 (3.75%) will have a diagnosis of angina.

It is unknown how many patients are managed solely in the primary care setting but 71% of patients referred to a cardiologist come from primary care physicians.8

Incidence

In 2017, there were 1.7 million inpatient episodes related to all cardiovascular diseases, with 4.4% of these for angina pectoris5 in the UK. Globally, CVD is responsible for 72.7 million hospital admissions in 2017, 18 million of which are in Europe.

Men have a greater number of admissions related to CVD and angina. Since 2010, there has been a 4.9% increase in CVD admissions in the UK.

Patients see their GP between 0.5–3 times per year for consultations related directly to their angina.9,10 Contact rates10 per 1,000 population is 14 for both sexes, with men having a higher contact rate of 15.7 compared to 12.3 for women. Contact rates rise with age, increasing to 55.5 in those aged over 75 years compared to 14.3 in those aged 45–54, with no difference between the sexes.

Prognosis

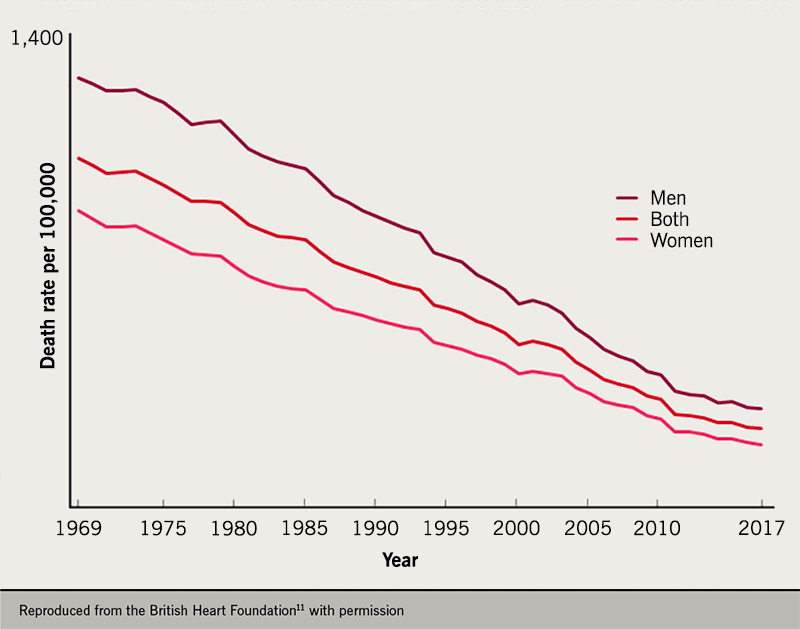

Mortality from CVD has dramatically declined since the 1960s. In 2017, CVD mortality in the UK was 279 per 100,000 compared to 1,045 per 100,000 in 1969.5,11 If current trends continue by 2030, there will be an estimated 36,000 fewer deaths from coronary heart disease (CHD).12

Table 1. Prognosis of angina patients at four-year end point

| End point at four years | Percentage of patients |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke | 16.3% |

| Cardiovascular death | 8.4% |

| MI | 4.8% |

| Stroke | 5.4% |

| All-cause mortality | 12.6% |

| Heart failure | 11% |

| Unstable angina | 15.2% |

| Cardiovascular hospital admission | 26.9% |

| Coronary revascularisation | 11.4% |

| Adapted from Eisen A et al.13 Key: MI = myocardial infarction |

|

Angina is not benign and prognosis varies; recent-onset angina or worsening symptoms are cause for concern. Over four years, 16.3% of patients with angina will have a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke (table 1).13 There is a high burden of heart failure, hospital admissions and the requirement to undergo revascularisation.

Those with angina compared to those with known coronary artery disease but no anginal symptoms have a poorer prognosis and a 19% increase in cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke.13 Those with more frequent anginal symptoms are more likely to be admitted, undergo revascularisation and have an increased mortality.14,15

Stable angina in women has previously been considered less-severely prognostic than in men to the extent that it has been referred to as a ‘soft’ diagnosis.16 Women and men have similar outcomes in respect to cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke16 and are less likely to have had invasive or non-invasive investigation, and receive suboptimal pharmacological therapy. Coronary heart disease (CHD) kills twice as many women in the UK as breast cancer.11

Regional variation

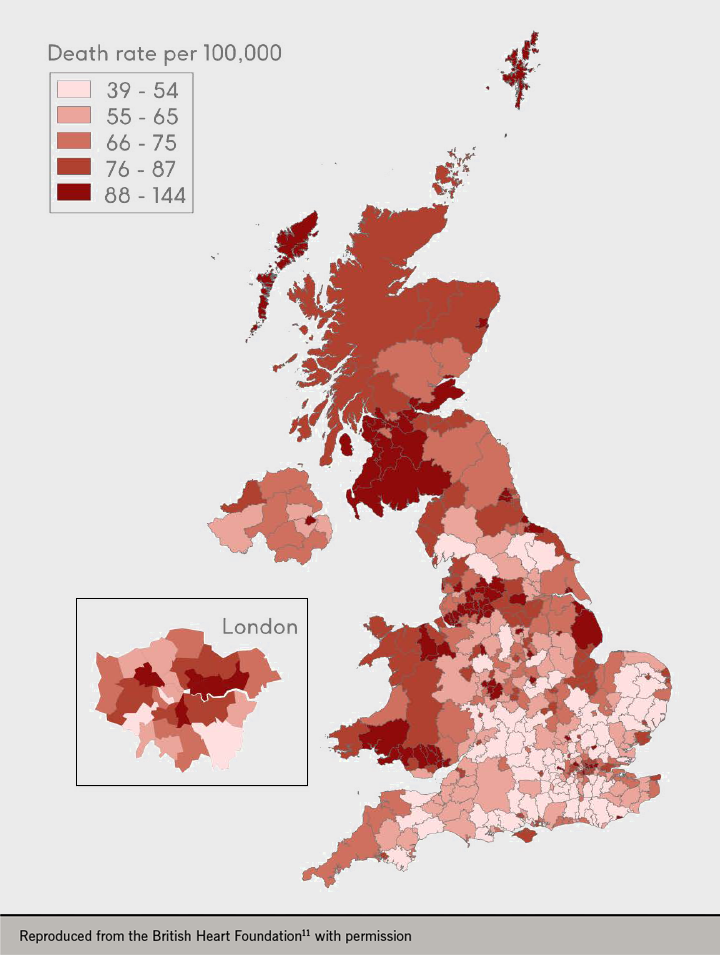

An estimated 2.3 million people are living with CHD in the UK.11 Angina pectoris is the commonest clinical manifestation of CHD. Within the UK, the incidence and prevalence of angina is not spread equally. There is a classical North-South divide, with the North having a greater burden of disease. Scotland had 348 per 100,000 deaths from CVD in 2017 compared to 271 per 100,000 in England.

Regionally in England, the South East had the lowest mortality (249 per 100,000) followed closely by the East of England and London. The North West had the highest mortality (301 per 100,000) with Yorkshire Humber and the North East being the second and third highest respectively. If all regions had the same mortality rate as Chelsea and Kensington, there would be 42,300 fewer deaths annually in the UK.17

CVD is heavily influenced by deprivation, with the most deprived having significantly higher rates of mortality compared to the least deprived (figure 3).11 Deprivation in the UK follows the north-south divide, with the South East being the least deprived area of the UK.

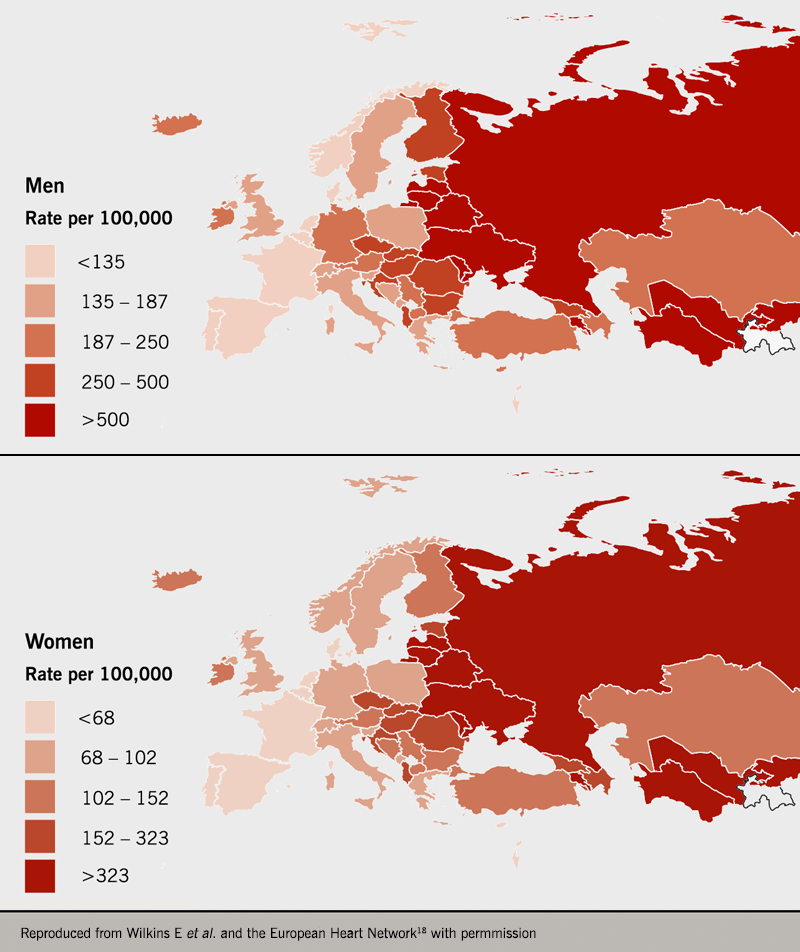

Each year cardiovascular disease (CVD) causes 3.9 million deaths in Europe and over 1.8 million deaths in the European Union (EU). Within Europe, the highest mortality for ischaemic heart disease is found in Eastern and Central Europe compared to Northern, Western and Southern Europe (figure 4).18 The lowest mortality is 77 per 100,000 in France compared to 700 per 100,000 in Lithuania. The UK is middle order and has similar mortality to Poland and Slovenia.

Ethnicity

The genetic contribution to the development of atherosclerosis has been calculated as being as high as 57%.19 This makes atherosclerosis a complex genetic disease with a significant environmental component.

South Asians have a higher risk for the development of CVD when compared to White and Black ethnicities. In the UK, South Asians have a 67% higher risk of incident stable angina, MI, and an 82% high risk of unstable angina when compared to Whites.20 South Asians develop CVD younger with 69% being diagnosed in those under 60 years of age compared to 48% in Whites. Black patients in the UK exhibit a lower risk of stable angina, unstable angina and CHD.

These findings of excess risk in South Asians persist after adjusting for traditional CVD risk factors, which supports the role of ethnicity in the risk of developing CVD.21 Screening for CVD should be prioritised in South Asians, especially at a younger age.

Cost

Beyond the human cost, the total annual healthcare costs for CVD is £9 billion11 in the UK. An estimated £19 billion is lost to the UK economy from CVD due to premature death, disability and informal costs.11 Half of these costs are spent on inpatient care and a quarter on medications.5 The average length of stay for MI in the UK is seven days.18

Specifically, for CHD in 2014, the UK spent a total of £953 million with £346 million spent in primary care prescribing and nearly as much (£314 million) on unscheduled care.5 CHD total spend was equal to the combined spend for stroke and cardiac rhythm disorders.

In England, 6–7% of the total healthcare budget goes into CVD, with CHD being responsible for 1.5% of the total NHS England spend.5 Regionally, the North spends £83 per head on CVD while London spends the least at £68 per head. Costs are higher outside England: CVD spend per head of the population is £150 in Wales and also in Scotland, with the highest cost per head at £224 being in Northern Ireland.5

CVD costs the European Union (EU) economy an estimated €210 billion yearly: 50% of this is direct healthcare costs with the residual being productivity loss and informal costs.18 CHD makes up 28% of the total cost to the EU. There is a similar split of spending in the EU to the UK, with 50% being inpatient cost and 25% medications.

In the next 50 years, the EU22 will see a projected population growth of around nine million but as the population ages and enters retirement, the working-age population will contract by around 41 million during this time. Within the UK this is estimated to increase the requirement for ageing-related costs by more than 3% of gross domestic product (GDP).

CVD will thus remain an important healthcare cost and targeting its determinants is essential as many have commonality with risk factors for dementia and cancer, both diseases that have caught up with CVD in terms of morbidity and mortality.

Key learning points

- Chronic stable angina is common in both sexes and its burden increases with age.

- Mortality from CVD has significantly improved over the past 50 years.

- CVD is not benign and is associated with hospitalisation, revascularisation, myocardial infarction and cardiovascular death.

- There are significant regional disparities within the UK and Europe.

- South Asians have higher risk of CVD with earlier onset.

- Healthcare and economic costs are significant.

close window and return to take test

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Chest pain of recent onset: assessment and diagnosis. Clinical guideline [CG95]. London: NICE, 2010 (updated November 2016). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg95/resources/chest-pain-of-recent-onset-assessment-and-diagnosis-pdf-975751036117 (last accessed 10th September 2019).

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Global Health Authorty data: top 10 causes of death. WHO. 2019. https://www.who.int/gho/mortality_burden_disease/causes_death/top_10/en/ (last accessed 10th September 2019).

- Office for National Statistics (GB). Deaths registered in England and Wales 2018. London: ONS, August 2019. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/datasets/deathsregisteredinenglandandwalesseriesdrreferencetables (last accessed 10th September 2019).

- British Heart Foundation. Cardiovascular disease statistics 2014. London: British Heart Foundation, 2014. https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/publications/statistics/cardiovascular-disease-statistics-2014 (last accessed 10th September 2019).

- British Heart Foundation (BHF). Heart and circulatory disease statistics 2019. London: BHF, 2019. https://www.bhf.org.uk/what-we-do/our-research/heart-statistics/heart-statistics-publications/cardiovascular-disease-statistics-2019 (last accessed 18th September 2019).

- Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2949-3003. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht296

- Office for National Statistics (GB). Health Survey for England 2017 Cardiovascular Diseases. London: ONS, 2018. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/9B/B999D6/HSE17-CVD-rep.pdf (last accessed 10th September 2019).

- Daly CA, Clemens F, Sendon JLL, et al. The initial management of stable angina in Europe, from the Euro Heart Survey. Eur Heart J 2005;26:1011-22. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehi109

- Stewart S, Murphy NF, Murphy N, Walker A, McGuire A, McMurray JJ V. The current cost of angina pectoris to the National Health Service in the UK. Heart 2003;89:848-53. https://doi.org/10.1136/heart.89.8.848

- Murphy NF, Simpson CR, MacIntyre K, McAlister FA, Chalmers J, McMurray JJ V. Prevalence, incidence, primary care burden and medical treatment of angina in Scotland: age, sex and socioeconomic disparities: a population-based study. Heart 2006;92:1047-54. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2005.069419

- British Heart Foundation (BHF). UK factsheet August 2019. London: BHF, 2019. https://www.bhf.org.uk/-/media/files/research/heart-statistics/bhf-cvd-statistics-uk-factsheet.pdf?la=en (last accessed 13th September 2019)

- Guzman Castillo M, Gillespie DOS, Allen K, et al. Future declines of coronary heart disease mortality in England and Wales could counter the burden of population ageing (van Baal PHM, ed). PLoS One 2014;9(6):e99482. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0099482

- Eisen A, Bhatt DL, Steg PG, et al. Angina and future cardiovascular events in stable patients with coronary artery disease: insights from the Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) Registry. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5:e004080. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.004080

- Mozaffarian D, Bryson CL, Spertus JA, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. Anginal symptoms consistently predict total mortality among outpatients with coronary artery disease. Am Heart J 2003;146:1015-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00436-8

- Beatty AL, Spertus JA, Whooley MA. Frequency of angina pectoris and secondary events in patients with stable coronary heart disease (from the Heart and Soul Study). Am J Cardiol 2014;114:997-1002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.07.009

- Hemingway H, McCallum A, Shipley M, Manderbacka K, Martikainen P, Keskimäki I. Incidence and prognostic implications of stable angina pectoris among women and men. JAMA 2006;295:1404. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.12.1404

- British Heart Foundation (BHF). Regional social differences in coronary heart disease 2008. London: BHF, 2008. https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/publications/statistics/regional-and-social-differences-in-coronary-heart-disease-2008 (last accessed 11th September 2019).

- Wilkins E, Wilson L, Wickramasinghe K, et al. European cardiovascular disease statistics 2017. Brussels: European Heart Network, 2017. http://www.ehnheart.org/cvd-statistics.html (last accessed 11th September 2019).

- Zdravkovic S, Wienke A, Pedersen NL, Marenberg ME, Yashin AI, De Faire U. Heritability of death from coronary heart disease: a 36-year follow-up of 20 966 Swedish twins. J Intern Med 2002;252:247-54. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01029.x

- George J, Mathur R, Shah AD, et al. Ethnicity and the first diagnosis of a wide range of cardiovascular diseases: associations in a linked electronic health record cohort of 1 million patients (Editor: Obukhov AG). PLoS One 2017;12:e0178945. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178945

- Tillin T, Hughes AD, Mayet J, et al. The relationship between metabolic risk factors and incident cardiovascular disease in Europeans, South Asians, and African Caribbeans: SABRE (Southall and Brent Revisited)—A Prospective Population-Based Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:1777. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2012.12.046

- Ageing Working Group of the Economic Policy Committee and the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. 2018 Ageing report: policy challenges for ageing societies | European Commission. Brussels: European Commission, 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/info/news/economy-finance/policy-implications-ageing-examined-new-report-2018-may-25_en (last accessed 13th September 2019).

All rights reserved. No part of this programme may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers, Medinews (Cardiology) Limited.

It shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent.

Medical knowledge is constantly changing. As new information becomes available, changes in treatment, procedures, equipment and the use of drugs becomes necessary. The editors/authors/contributors and the publishers have taken care to ensure that the information given in this text is accurate and up to date. Readers are strongly advised to confirm that the information, especially with regard to drug usage, complies with the latest legislation and standards of practice.

Healthcare professionals should consult up-to-date Prescribing Information and the full Summary of Product Characteristics available from the manufacturers before prescribing any product. Medinews (Cardiology) Limited cannot accept responsibility for any errors in prescribing which may occur.