Introduction

Before initiating oral anticoagulant therapy, the benefits of treatment must be weighed against the risks of bleeding. Relevant risk assessment tools, such as CHA2DS2-VASc, HAS-BLED or ORBIT (see modules 3 and 4), can be used to determine a patient’s thrombotic and individual bleeding risks, and to guide management decisions e.g. whether to start anticoagulant therapy, if so with what drugs, the duration of therapy, whether gastroprotection is required, and managing any factors that may increase the risk of bleeding (e.g. optimisation of blood pressure).

It is good practice before initiating anticoagulants to ensure a full coagulation screen has been undertaken (including international normalised ratio [INR] and activated partial thromboplastin time [APTT]) to identify any underlying coagulation disorders, as well as a full blood count, and renal and liver function tests.

Pharmacists play an integral role as members of a multidisciplinary team, ensuring that patients receive the correct drug and dose in a timely manner. They must also consider patient factors such as renal and hepatic dysfunction, as well as drug factors, such as interactions or concomitant drugs predisposing the patient to a greater risk of adverse effects (e.g. bleeding with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]).

It is imperative that we are aware of the responsibilities for all anticoagulant therapy – that is:

- to ensure the anticoagulant is appropriate for the individual patient (involving the patient in decision making)

- to initiate anticoagulant treatment with appropriate liaison between prescribers and anticoagulation clinics for ongoing monitoring and supply. This should take into consideration the needs of the patient (which may include home monitoring and initial supply of reagent strips)

- to ensure the patients receive the relevant anticoagulant card, and particularly for warfarin, the monitoring book, which allows any healthcare professional to review INR control

- to ensure the patient is aware of their treatment plan, how they will be followed up and how to obtain medical help in the event of any adverse effects.

Commissioning effective anticoagulation services

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a major risk factor for stroke and a contributing factor to one in five strokes. Treatment with an oral anticoagulant reduces the risk of stroke in someone with AF by two thirds.1 Between April 2018 and March 2019, 39.1% of patients with known AF who had a stroke had not been prescribed anticoagulation prior to their stroke.1 By 2029, the NHS aims to ensure that 85% of the expected number of people with AF are detected and 90% of patients who are at risk of a stroke from AF are optimally anticoagulated.2

There is no standard definition of what constitutes an anticoagulation service. Models of care have evolved to meet the needs of local populations. There have been concerns around the variation in the activities, and in the quality and safety of anticoagulation therapy across the country. Anticoagulation UK have produced a Framework Service Specification for anticoagulation management for people with AF.3 This provides NHS commissioners and providers with the key components to include in an anticoagulation service in line with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance and quality standards. During the COVID-19 pandemic, NHS England produced a document to advise service providers how to adapt anticoagulation services to accommodate COVID-19 restrictions whilst still meeting the needs of the population.4 These changes have inevitably changed the way in which anticoagulation services are being delivered, with virtual clinics becoming more common.

Counselling patients initiated on warfarin and DOACs

Due to their unpredictable pharmacokinetics and narrow therapeutic windows, routine coagulation monitoring using INR is essential for vitamin K antagonist (VKA) anticoagulants. Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) demonstrate predictable and stable pharmacokinetics and do not require routine coagulation monitoring.

The need for regular monitoring with VKAs must be explained to the patient. The INR can define how quickly the blood clots in relation to someone who is not on warfarin, i.e. a value of three indicates that it will take three times longer for someone’s blood to clot in comparison to someone not on warfarin. The patient will need to appreciate that too low an INR (INR <2) will not give the full benefit of preventing strokes, whereas too high an INR (INR >4) can put the patient at risk of bleeding or bruising that can at times be serious.

When patients first start taking warfarin, they will attend the anticoagulant clinic frequently for INR monitoring, as their dosage is adjusted to achieve the desired INR. Most people find that once they are established on warfarin, their INR is fairly stable and they need only attend the clinic every 12 weeks.

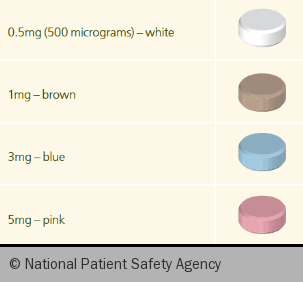

There are multiple factors that can influence the efficacy of warfarin, including liver function, age, concomitant medicines, dietary intake of leafy vegetables, and alcohol. As such, the required dose of warfarin (figure 1) needs to be tailored to each individual and may change from time to time, for example when drinking more alcohol, or taking a course of antibiotics.

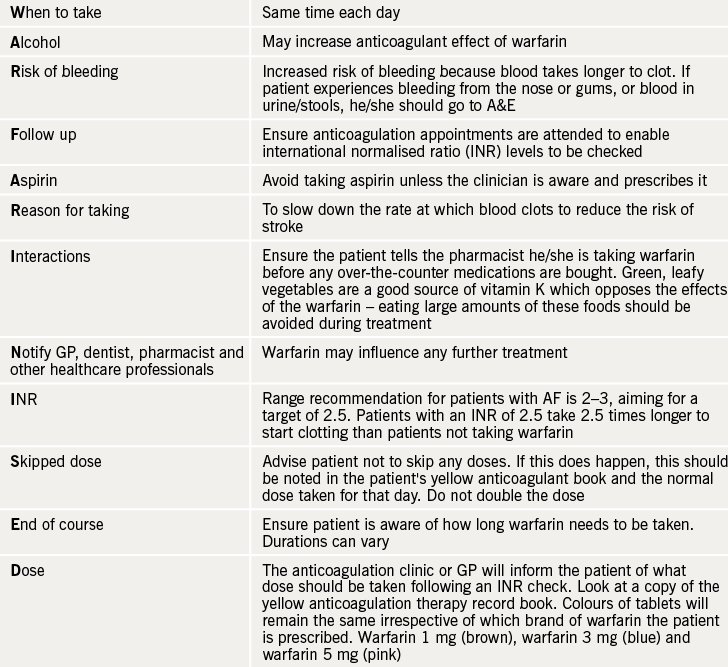

WARFARINISED (see table 1) is a good acronym to remember the important counselling points for patients starting therapy with warfarin.

Considerations for use of DOACs

DOACs are covered in more detail in previous modules (modules 3 and 4). All DOACs are partially eliminated via the kidney, with the proportion of renal excretion varying amongst each DOAC. Assessment of kidney function is thus important to estimate their clearance from the body. Based on these properties, apixaban, edoxaban and rivaroxaban are contraindicated in patients with AF who have creatinine clearance (CrCl) <15 mL/min and dabigatran is contraindicated in patients with CrCl <30 mL/min.5

DOACs are all substrates of P-glycoprotein (Pgp), a transport protein present in enterocytes and the liver, which reduces the bioavailability of its substrates.6 Hence, even if the potential for drug–drug interactions is less with DOACs compared to VKAs, there is still potential for interactions. Thus caution is required when DOACs are co-administered with certain drugs and interactions should always be checked using a reliable source. By contrast, drug–food interactions are not expected with the DOACs as vitamin K intake does not influence their mechanism of action.6

In addition to the risk of drug-related problems due to pharmacological properties of oral anticoagulants (bleeding and interactions), both health care professionals and patients should be actively supported to ensure safe and effective medication care. Studies have indicated the potential for errors associated with oral anticoagulants and they are commonly featured on hospital critical medications lists. They are often under dosed, inadequately monitored, inadequately stored, and not taken as prescribed, increasing the risk for adverse drug events in patients receiving oral anticoagulation.7

Pharmacists have a role in ensuring appropriate dosing of DOACs is undertaken based on the criteria set out in the summary of product characteristics (SmPC) for each DOAC.5 It is worth noting that clinical trials with DOACs for stroke prevention in AF used the Cockcroft-Gault equation to estimate CrCl as a measure of renal function, and subsequent assessment of drug eligibility and dosing were determined. A cross-sectional study demonstrated when the Modified Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula is used (which is a more widely available and more commonly used equation for assessing CrCl) rather than the Cockcroft-Gault formula, patients would receive higher doses or be deemed incorrectly suitable for eligibility for DOAC treatment. The safety and efficacy of using the MDRD equation has not been established.8 All DOAC trials used actual body weight to calculate renal function rather than ideal or adjusted body weight. For patients at extremes of body weight, local policies differ on whether adjusted or ideal body weight is used as an alternative to actual body weight.

To safeguard appropriate prescribing for DOACs in non-valvular AF (NVAF), a simple ABCD can be used whereby:

- A = age – certain DOACs require a consideration for dose reduction depending on age

- B = body weight – certain DOACs require a dose reduction if body weight <60 kg

- C = creatinine clearance (Cockroft-Gault) – all DOACs are dependent on renal function and require a dose reduction as renal function decreases

- D = check for drug interactions – all DOACs may interact with p-glycoprotein inhibitors or drugs that may induce or inhibit cytochrome P450 system – check against product characteristics.

Note that for dabigatran and rivaroxaban, indigestion is a known adverse effect and, as such, patients should be counselled and gastric protection considered as appropriate. All of the DOACs have a shorter half-life than warfarin, such that the drug concentration (and, thus, anticoagulant effect) would decline soon after one or more doses are missed. If the patient misses a dose of their DOAC, they should consult the patient information leaflet or booklet for advice on when to take their next dose. Patients should be counselled on the importance of adherence and that medication should not be stopped without consulting with the initiating practitioner. Supply arrangements vary in different areas so it is imperative the patient is aware of how to obtain further supplies of medication to prevent missed doses. In the event of the patient experiencing adverse effects, they should be given advice on how to manage these and how to get help depending on the severity of the adverse effect.

Lastly, ensure patients receive their respective anticoagulant alert card and carry it with them at all times, so that it can be presented to any relevant healthcare professional who is managing their care.

Switching between anticoagulants

The NICE guideline9 on anticoagulation in AF recommends the use of a DOAC as the first-line option, with no particular DOAC being used as a preference. When a DOAC is contraindicated, a VKA should be considered.

Patients who are already on VKA therapy will need to be reviewed with a view to switching to a DOAC if the following apply:

- two INR values higher than 5 or one INR value higher than 8 within the past six months

- two INR values less than 1.5 within the past six months

- a time in therapeutic range (TTR) of less than 65%.

For patients who are stable on a VKA, the option to switch should be discussed at the next routine appointment. Conversely, patients well established on a DOAC, may need to switch to a VKA, for example, if they are initiated on an interacting medication or if they experience a decline in renal function which falls below the threshold for use of DOACs. Patients may also need advice on how to manage their anticoagulation if they are going for dental or surgical procedures. The management of this depends on the anticoagulant in use, the type of procedure being undertaken, and the patient’s renal function. Specialist advice from an anticoagulation service should be sought for this.

The dosing recommendations on switching can be found in the SmPCs for each product.5

Role of the community pharmacist in optimising patient care

Patients have regular access to community pharmacists, who can add to the care of a patient medicated with anticoagulation therapy. Anticoagulants are one of the classes of medicines most frequently identified as causing preventable harm and admission to hospital.

A drug safety update was released in June 202010 outlining the importance of remaining vigilant for signs and symptoms of bleeding in patients on anticoagulants. Community pharmacists are well placed to ensure patients are on the correct dose of anticoagulant and also remind patients of the signs and symptoms of bleeding to look out for and to read the patient information leaflet that accompanies their medication.

The guidance also suggests that pharmacists dispensing clinically significant interacting medicines, such as antibiotics, or another medication that may increase the risk of bleeding (e.g. selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs), or NSAIDs, should take additional safety precautions. These include:

- informing the anticoagulant service that an interacting medicine has been prescribed

- ensuring additional INR blood tests have been arranged for patients on warfarin to monitor any changes

- advising patients to be aware of signs of bleeding or bruising and how to seek help in the event of these.

More recently, the New Medicines Service (NMS)11 has been introduced as an advanced service to the community pharmacy contract. The service provides support for people with long-term conditions newly prescribed a medicine, helping to improve medicine adherence. The optimal use of appropriately prescribed medicines is vital to the self-management of most long-term conditions, but reviews conducted across disease states are consistent in estimating that between 30–50% of prescribed medicines are not taken as recommended. This represents a failure to translate the technological benefits of new medicines into health gain for individuals. Sub-optimal medicine use can lead to inadequate management of long-term conditions, and a cost to the patient, the NHS, and to society.

The NMS currently focuses on specific patient groups and conditions, including anticoagulant therapy.

The service is such that all patients newly prescribed an anticoagulant, for example, will be eligible to receive it. The NMS provides an interview schedule to facilitate discussions between pharmacist and patient. These include:

- Have you started taking your new medicine yet?

- How are you getting on with it?

- Are you having any problems with your new medicine, or concerns about taking it?

If you are a hospital-based pharmacist or prescriber, consider referral to the NMS. This will provide the reassurance that any information provided to the patient is reinforced by community pharmacy colleagues, and that any problems patients experience will be addressed and discussed.

close window and return to take test

References

1. Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme (SSNAP), Outcome data at discharge from inpatient care for patients with prior AF who are not on anticoagulation. Version 1, updated June 2019. Available from: https://www.strokeaudit.org/results/Clinical-audit/National-Results.aspx [Accessed 29 July 2021].

2. Public Health England, Health matters: preventing cardiovascular disease, 14 February 2019. Available from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-preventing-cardiovascular-disease/health-matters-preventing-cardiovascular-disease [Last accessed 10th August 2021]

3. Anticoagulation UK. Framework Service Specification for anticoagulation management of people with atrial fibrillation. Published September 2020. https://anticoagulationuk.org/downloads/ACUK%20Anticoagulation%20Service%20Specification%20-%20Final.pdf [last accessed 10th August 2020]

4. NHS England and NHS Improvement. Clinical guide for the management of anticoagulation services during the coronavirus pandemic. Published November 2020, updated February 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/COVID-19/Specialty-guides/specialty-guide-anticoagulant-services-and-coronavirus.pdf [last accessed 10th August 2021]

5. Summary of Product Characteristics for apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban, dabigatran and warfarin. Electronic Medicines Compendium 2021. Available from https://emc.medicines.org.uk/emc/ [last accessed 10th August 2021]

6. Salem J-EJ, Sabouret P, Funck-Brentano C, Hulot J-S. Pharmacology and mechanisms of action of new oral anticoagulants. Fundam Clin Pharmacol [Internet] 2015;29:10–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcp.12091

7. Cutler TW, Chuang A, Huynh TD, et al. A retrospective descriptive analysis of patient adherence to dabigatran at a large academic medical center. J Managed Care Specialty Pharm 2014;20:1028–34. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.10.1028

8. Maccallum PK, Mathur R, Hull SA, et al. Patient safety and estimation of renal function in patients prescribed new oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2013;3(9):e003343. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003343

9. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Atrial fibrillation: the management of atrial fibrillation. Clinical guideline [NG196]. London: NICE, April 2021, last modified June 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng196 [last accessed 10th August 2021]

10. Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. MHRA Drug safety update, 29 June 2020. https://psnc.org.uk/our-news/mhra-drug-safety-update-june-2020/ [last accessed 29 July 2021]

11. Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. Services and Commissioning. New Medicine Service. https://psnc.org.uk/services-commissioning/advanced-services/nms/ [last accessed 10th August 20201]

Further reading

Hicks T, Stewart F, Eisinga A. NOACs versus warfarin for stroke prevention in patients with AF: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart 2016;3:e000279. http://doi.org/10.1136/openhrt-2015-000279

Disclaimer:

Medical knowledge is constantly changing. As new information becomes available, changes in treatment, procedures, equipment and the use of drugs become necessary. The editors/authors/contributors and the publishers Medinews (Cardiology) Ltd have taken care to ensure that the information given in this text is accurate and up to date at the time of publication.

Readers are strongly advised to confirm that the information, especially with regard to drug usage, complies with the latest legislation and standards of practice. Medinews (Cardiology) Limited advises healthcare professionals to consult up-to-date Prescribing Information and the full Summary of Product Characteristics available from the manufacturers before prescribing any product. Medinews (Cardiology) Limited cannot accept responsibility for any errors in prescribing which may occur.

The opinions, data and statements that appear are those of the contributors. The publishers, editors, and members of the editorial board do not necessarily share the views expressed herein. Although every effort is made to ensure accuracy and avoid mistakes, no liability on the part of the publisher, editors, the editorial board or their agents or employees is accepted for the consequences of any inaccurate or misleading information.

© Medinews (Cardiology) Ltd 2021. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers, Medinews (Cardiology) Ltd. It shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent.

All rights reserved. No part of this programme may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers, Medinews (Cardiology) Limited.

It shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent.

Medical knowledge is constantly changing. As new information becomes available, changes in treatment, procedures, equipment and the use of drugs becomes necessary. The editors/authors/contributors and the publishers have taken care to ensure that the information given in this text is accurate and up to date. Readers are strongly advised to confirm that the information, especially with regard to drug usage, complies with the latest legislation and standards of practice.

Healthcare professionals should consult up-to-date Prescribing Information and the full Summary of Product Characteristics available from the manufacturers before prescribing any product. Medinews (Cardiology) Limited cannot accept responsibility for any errors in prescribing which may occur.