Introduction

In this programme, module 1 has explained the mechanisms and functions of haemostasis, and of the importance of the balance between coagulation and the dual processes of inhibition and fibrinolysis. Module 2 has considered the pathology of arterial thrombosis, and the use of antiplatelet agents to treat or prevent this. Module 3 has looked at the therapeutic indications for anticoagulants in acute coronary syndromes and non-valvular atrial fibrillation (AF), as well as their use in cardioversion for AF. This module also considers the choice of anticoagulant for stroke prevention, as well as peripheral arterial disease, venous thromboembolism and the expanding role of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs).

Peripheral arterial disease

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is a cardiovascular disease affecting arteries in the legs. It is most commonly due to atherosclerosis of an artery (the pathophysiology of which was discussed in module 1). The Edinburgh Artery Study (EAS) described the prevalence of asymptomatic and symptomatic PAD by performing the World Health Organisation questionnaire on intermittent claudication and ankle brachial systolic pressure on 1,592 participants aged between 55 to 74 years. This found the prevalence of:

- intermittent claudication was 4.5% (95% CI: 3.5–5.5%)

- major asymptomatic disease causing a significant impairment of blood flow was 8.0% (95% CI: 6.6–9.4%); this group also had more evidence of ischaemic heart disease than the normal population with a relative risk of 1.6 (95% CI 1.3–1.9%).

The study confirmed that intermittent claudication was equally common in men and woman, and that prevalence increases with age and a lower social class.1

Intermittent claudication is pain that occurs on walking and improves with rest. This can become a critical ischaemia if:2

- rest pain develops (this may be worse in bed when the leg is elevated)

- the leg is red/purple in colour when not elevated

- there is early pallor on elevation

- there are skin changes including impaired wound healing and absent foot pulses.

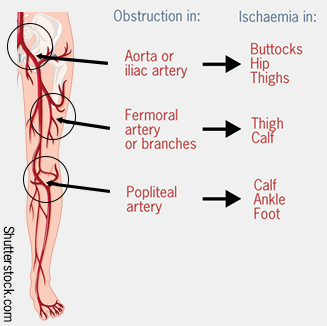

The site of where symptoms arises varies according to the artery involved (see figure 1).

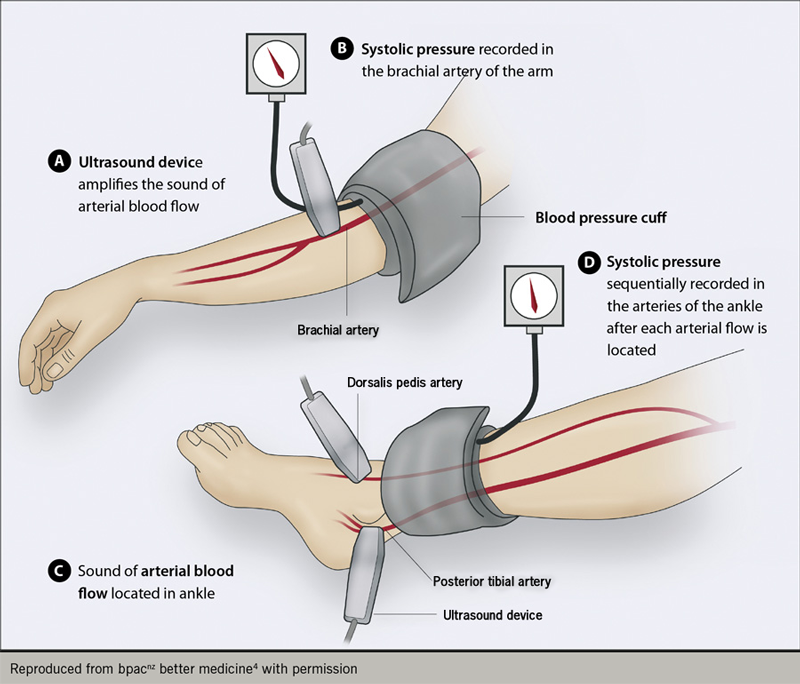

The ankle brachial pressure index can be used in the assessment of PAD but needs to be used with caution in those with diabetes due to medial sclerosis. It compares the blood pressure in the ankle and arm. If the results are normal, it does not exclude a diagnosis of PAD (see figure 2).3

Management of PAD2

If available, all patients with intermittent claudication should receive a supervised exercise programme and risk factor modification. Secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in people with PAD includes:

- smoking cessation

- diet, weight management and exercise

- lipid modification and statin therapy

- prevention, diagnosis and management of diabetes and hypertension

- antiplatelets.

They should be referred for consideration of angioplasty or bypass surgery when a supervised exercise programme has failed, and risk factors have been modified. Naftidrofuryl oxalate can be used if there is no improvement with exercise and patients do not wish to be referred for angioplasty or bypass surgery. This is a vasodilator agent with an antagonistic effect on 5-HT2 receptors of smooth muscle cells. It also activates intracellular aerobic metabolism by reducing lactic acid and increasing adenosine triphosphate (ATP). This action protects against ischaemia. This action protects against ischaemia. Further information is available in reference 5.

The DVLA may need to be informed if peripheral vascular disease (PVD) occurs.

Current guidelines suggest the use of clopidogrel 75 mg once daily as the preferred antiplatelet agent, or aspirin alone if clopidogrel is contraindicated or not tolerated.6

The Cardiovascular Outcomes for People Using Anticoagulation Strategies (COMPASS) trial,7 a multi-centre, double-blind, randomised, controlled trial, has compared:

- rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily with aspirin 100 mg once daily

- rivaroxaban 5 mg twice daily (with aspirin placebo once daily)

- aspirin 100 mg once daily (with rivaroxaban placebo twice daily).

Eligible patients had a history of PAD of the lower extremities, of the carotid arteries or coronary artery disease with an ankle brachial pressure index <0.90. Primary outcome was cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction or stroke; the primary PAD outcome was major adverse limb events including major amputation. The study recruited 7,470 patients with PAD from 558 centres. It concluded that low-dose rivaroxaban taken twice daily with aspirin reduced major adverse limb events when compared with aspirin alone (1.2% vs. 2.2% respectively; HR, 0.54: 95% CI: 0.35–0.84), although there was an increase in major bleeding (not in fatal or critical bleeding). The most common site for bleeding was gastrointestinal. Rivaroxaban alone reduced major adverse limb events but increased major bleeding.

On the basis of this study, rivaroxaban (at low dose) plus aspirin is approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)8 as an option for preventing atherothrombotic events in adults with coronary artery disease or symptomatic peripheral artery disease who are at high risk of ischaemic events.

Venous thromboembolism

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). The pathophysiology of VTE is discussed in module 1. Provoking factors must be considered when a VTE is diagnosed (see table 1).

Table 1. Detail of thombosis risk factors within the NICE VTE risk assessment tool

| Patient related | Admission related |

|---|---|

| Active cancer or cancer treatement | Significantly reduced mobility for 3 days or more |

| Age over 60 years | Hip or knee replacement |

| Dehydration | Hip fracture |

| Known thrombophilias | Total anaesthetic and surgical time over 90 minutes |

| Obesity (BMI over 30 kg/m2) | Surgery involving pelvis or lower limb with a total anaesthetic and surgical time over 60 minutes |

| One or more significant medical comorbidities (eg heart disease; metabolic, endocrine or respiratory pathologies; acute infectious diseases; inflammatory conditions) | Acute surgical admission with inflammatory or intra-abdominal condition |

| Personal history or first degree relative with a history of VTE | Critical care admission |

| Use of hormone replacement therapy | Surgery with significant reduction in mobility |

| Use of oestrogen-containing contraceptive therapy | |

| Varicose veins with phlebitis | |

| For women who are pregnant or have given birth within the previous six weeks | |

| Reproduced from NICE9 with permission Key: BMI = body mass index; VTE = venous thromboembolism |

|

If no risk factors are found, it must be remembered that the prevalence of undiagnosed cancer in patients who have an unprovoked VTE is 6.1% at presentation, increasing to 10% at 12 months.10 Extensive screening in this cohort for an undiagnosed malignancy is a contentious issue. Studies have shown that extensive screening can identify underlying malignancies at an earlier stage.11,12 The advantages of screening, however, must be balanced against false positives, uncertain benefit with respect to eventual clinical outcomes, potential anxiety to the patient, and resource consumption. Based on a 2017 Cochrane review13 of four randomised control trials, NICE have advised that in those over the age of 40 with an unprovoked VTE, cancer screening investigations should be targeted to those with relevant clinical signs and symptoms, but not performed routinely.14

Treatment options for VTE, since the advent of DOACs, have increased allowing for more patient choice. Table 215–28 shows the licenses of the DOACs. They have been viewed favourably due to the reduced frequency of blood tests required and the generally ‘one size fits all’ nature of the medications. There is ongoing research into the use of these medications at extremes of body weight29 and use outside of the prescribing parameters. Available data suggest that rivaroxaban and apixaban can be adequate for treatment of VTE in patients with obesity regardless of body weight and BMI.30

Table 2. NICE technology appraisal guidance on DOACs15–28

| Indication | Apixaban | Dabigatran etexilate | Edoxaban | Rivaroxaban |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevention of VTE after elective hip or knee replacement | Recommended as an option: TA24516 | Recommended as an option: TA15717 | Not licensed for this indication | Recommended as an option: TA17018 |

| Treatment and secondary prevention of DVT and/or PE | Recommended as an option: TA34119 | Recommended as an option: TA32720 | Recommended as an option: TA35421 | Recommended as an option: TA26122 and TA28723 |

| Prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in people with non-valvular AF | Recommended as an option in specified circumstances: TA27524 | Recommended as an option in specified circumstances: TA24925 | Recommended as an option in specified circumstances: TA35526 | Recommended as an option in specified circumstances: TA25627 |

| Prevention of adverse outcomes after acute management of ACS with raised biomarkers | Not licensed for this indication | Not licensed for this indication | Not licensed for this indication | Recommended as an option in specified circumstances: TA33528 |

| Reproduced from NICE17 with permission Key: ACS = acute coronary syndrome; AF = atrial fibrillation; DVT = deep vein thrombosis; NICE = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; PE = pulmonary embolism; TA = technology appraisal; VTE = venous thromboembolism |

||||

The duration of anticoagulation following a VTE is dependent on provoking risk factors and location so should be considered on an individual basis. Einstein Choice is a clinical trial that looked at patients with VTE who had completed six to 12 months of anticoagulation and had clinical equipoise for continuation of anticoagulation. It compared the use of reduced dose rivaroxaban (10 mg once daily) with standard dose rivaroxaban (20 mg) with aspirin (100 mg/day). Rivaroxaban at either dose was found to be more effective than aspirin in preventing recurrent VTE events without a significant increase in major bleeding.31 The Apixaban for Extended Treatment of Venous Thromboembolism (AMPLIFY-EXT) trial also suggested that apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily is an option for extended anticoagulation in VTE patients, when compared to placebo and apixaban at standard therapeutic dose (5 mg twice daily).32

Cancer-associated thrombosis (CAT)

Two studies have predominantly guided current management of VTE in cancer. These include the Comparison of LMWH versus Oral Anticoagulant Therapy for the Prevention of Recurrent VTE in Patients with Cancer (CLOT)33 and Comparison of Acute Treatments in Cancer Haemostasis (CATCH) study.34 As a result of these studies, low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) currently forms the cornerstone of treatment of VTE in cancer patients.

The evidence for the use of DOACs in the cancer cohort is expanding. Evidence has demonstrated that edoxaban is non-inferior to subcutaneous dalteparin35 for the treatment of VTE. Select-D, which compares DOACs and LMWH for the treatment of VTE in patients with cancer, has reported that rivaroxaban has a low VTE recurrence rate at six months.36 There are a number of other studies comparing DOACs and LMWH or warfarin. Recently published NICE14 and international guidance37 generally supports the use of DOACs in CAT, outside of those with a higher bleeding risk, particularly in gastrointestinal and genitourinary cancers, and in those with potential drug interactions.

Current guidelines suggest that treatment of cancer-associated thrombosis should be for at least six months, but prolonged treatment should be considered if the provoking risk factor is still present – for example, if the patient continues to have active cancer.38

Atrial fibrillation in cancer patients

A recent international survey of clinicians highlighted significant heterogeneity in the management of anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation (AF) patients with active cancer, with DOACs being preferred by most (62.6%) but LMWH use remaining substantial. There is encouraging early data to support use of DOACs over warfarin in AF cancer patients, but further prospective data would be desirable.39 The European Heart Rhythm Association 2018 guidance40 suggests DOACs may be considered on a case-by-case basis, taking into account factors such as patient preference and drug interactions. It also highlights the lack of evidence for LMWH efficacy in AF stroke prevention.

DOAC use in catheter ablation in AF

If pharmacological measures have been unsuccessful in controlling symptoms of AF, then left atrial catheter ablation can be considered.41 Those anticoagulated with warfarin (INR 2–3) should continue this during ablation. There are multiple studies comparing the use of uninterrupted warfarin and uninterrupted DOACs in this setting and there appears to be similar safety and efficacy data.42 Anticoagulation should be continued for at least eight weeks post-ablation.43

Future areas

The use of DOACs in more specialised areas is subject to ongoing study, such as in heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), cancer and venous thrombosis at unusual sites. DOACs, at standard dose, should be used with caution in thrombotic APS, and are certainly not recommended in higher risk patients, such as those with ‘triple positivity’ and/or an arterial thrombotic history.44

close window and return to take test

References

1. Fowkes F, Housley E, Cawood E, Macintyre C, Ruckley C, Prescott R. Edinburgh artery study: Prevalence of asymptomatic and symptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the general population. Int J Epidemiol 1991;20:384–92.

2. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Peripheral arterial disease: diagnosis and management. Clinical guideline [CG147]. London: NICE, August 2012, updated February 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG147 (last accessed 23rd October 2018)

3. Al-Qaisi M, Nott DM, King DH, Kaddoura S. Ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI): An update for practitioners. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2009;5:833–41. https://doi.org/10.2147/VHRM.S6759

4. bpacnz better medicine. The ankle brachial ankle pressure index: an underutilised tool in primary care? https://bpac.org.nz/bpj/2014/april/ankle-brachial.aspx (last accessed 23rd October 2018)

5. emc. Naftidrofuryl capsules BP 100 mg. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/24010/SPC/Naftidrofuryl+Capsules+100mg/ (last accessed 5th July 2021)

6. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Antiplatelet treatment. Clinical knowledge summaries. London: NICE, June 2018. https://cks.nice.org.uk/antiplatelet-treatment (last accessed 5th July 2021)

7. Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, Bosch J, et al. Rivaroxaban with or without aspirin in stable cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1319−30. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1709118

8. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Rivaroxaban for preventing atherothrombotic events in people with coronary or peripheral artery disease. Technology appraisal guidance [TA607], London: NICE, October 17th 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta607 [last accessed 15th July 2021]

9. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Venous thromboembolism in over 16s: reducing the risk of hospital-acquired deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. Clinical guideline (NG89). London: NICE, March 2018 . https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng89 (last accessed 23rd October 2018).

10. Carrier M, Le Gal G, Wells PS, Fergusson D, Ramsay T, Rodger MA. Systematic review: The trousseau syndrome revisited: Should we screen extensively for cancer in patients with venous thromboembolism? Cancer screening in patients with venous thromboembolism. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:323–33. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00007

11. Monreal M, Lensing A, Prins M, Bonet M, Fernández‐Llamazares J, Muchart J, Prandoni P, Jiménez JA. Screening for occult cancer in patients with acute deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost 2004;2:876–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00721.x

12. Piccioli A, Lensing AWA, Prins MH, Falanga A, Scannapieco GL, Ieran M, Cigolini M, Ambrosio GB, Monreal M, Girolami A, Prandoni P & for the SOMIT Investigators Group. Extensive screening for occult malignant disease in idiopathic venous thromboembolism: A prospective randomized clinical trial. J Thromb Haemost 2004;2:884–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00720.x

13. Robertson L, Yeoh SE, Stansby G, Agarwal R. Effect of testing for cancer on cancer- and venous thromboembolism (VTE)-related mortality and morbidity in people with unprovoked VTE. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews Published online 23rd August 2017. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010837.pub3. Updated 8th November 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010837.pub4 [last accessed 15th July 2021]

14. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Venous thromboembolic diseases: diagnosis, management and thrombophilia testing (NG158). London: NICE, March 2020. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng158 [last accessed 13th July 2021]

15. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Anticoagulants, including non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs). Key therapeutic topic (KTT16). London: NICE, February 2016, updated September 2019. [last accessed 13th July 2021]. www.nice.org.uk/advice/ktt16/chapter/evidence-context

16. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Apixaban for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after total hip or knee replacement in adults (TA245). London: NICE, January 2012. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta245 [last accessed 13th July 2021]

17. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Dabigatran etexilate for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after hip or knee replacement surgery in adults (TA157). London: NICE, September 2008. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta157 [last accessed 13th July 2021]

18. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Rivaroxaban for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after total hip or total knee replacement in adults (TA170). London: NICE, April 2009. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta170 [last accessed 13th July 2021]

19. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Apixaban for the treatment and secondary prevention of deep vein thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism (TA341). London: NICE, June 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta341 [last accessed 13th July 2021]

20. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Dabigatran etexilate for the treatment and secondary prevention of deep vein thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism (TA327). London: NICE, December 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta327 [last accessed 13th July 2021]

21. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Edoxaban for treating and for preventing deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism (TA354). London: NICE, August 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta354 [last accessed 13th July 2021]

22. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Rivaroxaban for the treatment of deep vein thrombosis and prevention of recurrent deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism (TA261). London: NICE, July 2012. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta261 [last accessed 13th July 2021]

23. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Rivaroxaban for treating pulmonary embolism and preventing recurrent venous thromboembolism (TA287). London: NICE, June 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta287 [last accessed 13th July 2021]

24. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Apixaban for preventing stroke and systemic embolism in people with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (TA275). London: NICE, February 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta275 [last accessed 13th July 2021]

25. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Dabigatran etexilate for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in atrial fibrillation (TA249). London: NICE, March 2012. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta249 [last accessed 13th July 2021]

26. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Edoxaban for preventing stroke and systemic embolism in people with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (TA355). London: NICE, September 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta355 [last accessed 13th July 2021]

27. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Rivaroxaban for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in people with atrial fibrillation (TA256). London: NICE, May 2012. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta256 [last accessed 13th July 2021]

28. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Rivaroxaban for preventing adverse outcomes after acute management of acute coronary syndrome (TA335). London: NICE, March 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta335 [last accessed 13th July 2021]

29. Czuprynska J, Patel JP, Arya R. Current challenges and future prospects in oral anticoagulant therapy. Br J Haematol 2017;178:838–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.14714

30. Martin KA, Beyer-Westendorf J, Davidson BL, Huisman MV, Sandset PM, Moll S. Use of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with obesity for treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism: Updated communication from the ISTH SSC Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation. J Thromb Haemost. 2021 Aug;19(8):1874–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.15358. Epub 2021 Jul 14.)

31. Weitz JI, Lensing AW, Prins MH, et al. Rivaroxaban or aspirin for extended treatment of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1211–22. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1700518

32. Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A, et al. Apixaban for Extended Treatment of Venous Thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2013;368:699–708. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1207541

33. Lee AY, Levine MN, Baker RI, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin versus a coumarin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med 2003;349:146–53. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa025313

34. Lee AY, Kamphuisen PW, Meyer G, et al. Tinzaparin vs warfarin for treatment of acute venous thromboembolism in patients with active cancer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015;314:677–86. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.9243

35. Raskob GE, van Es N, Verhamme P, et al. Edoxaban for the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2018;378:615–24 https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1711948

36. Young AM, Marshall A, Thirlwall J, et al. Comparison of an oral factor xa inhibitor with low molecular weight heparin in patients with cancer with venous thromboembolism: Results of a randomized trial (SELECT-D). J Clin Oncol 2018;36:2017–23. http://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2018.78.8034

37. Khorana AA, Noble S, Lee AYY, et al. Role of direct oral anticoagulants in the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost 2018;16:1891–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.14219

38. Watson HG, Keeling DM, Laffan M, et al. and the British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guideline on aspects of cancer-related venous thrombosis. Br J Haematol 2015;170:640–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.13556

39. Mosarla RC, Vaduganathan M, Qamar A, Moslehi J, Piazza G, Giugliano RP. Anticoagulation strategies in patients with cancer. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:1336–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.017

40. Steffel J, Verhamme P, Potpara TS, et al. The 2018 European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2018;39:1330–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy136

41. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Atrial fibrillation: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline (NG 196). London: NICE, April 2021, updated June 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng196 [last accessed 15th July 2021]

42. Cappato R, Marchlinski FE, Hohnloser SH, et al. Uninterrupted rivaroxaban vs. uninterrupted vitamin K antagonists for catheter ablation in non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2015;36:1805–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv177

43. Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 202;4:373–498. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612 [last accessed 15th July 2021]

44. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Drug safety update: Direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs): increased risk of recurrent thrombotic events in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome. Published online 19th June 2019. https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/direct-acting-oral-anticoagulants-doacs-increased-risk-of-recurrent-thrombotic-events-in-patients-with-antiphospholipid-syndrome [last accessed 15th July 2021]

Further reading

Disclaimer:

Medical knowledge is constantly changing. As new information becomes available, changes in treatment, procedures, equipment and the use of drugs become necessary. The editors/authors/contributors and the publishers Medinews (Cardiology) Ltd have taken care to ensure that the information given in this text is accurate and up to date at the time of publication.

Readers are strongly advised to confirm that the information, especially with regard to drug usage, complies with the latest legislation and standards of practice. Medinews (Cardiology) Limited advises healthcare professionals to consult up-to-date Prescribing Information and the full Summary of Product Characteristics available from the manufacturers before prescribing any product. Medinews (Cardiology) Limited cannot accept responsibility for any errors in prescribing which may occur.

The opinions, data and statements that appear are those of the contributors. The publishers, editors, and members of the editorial board do not necessarily share the views expressed herein. Although every effort is made to ensure accuracy and avoid mistakes, no liability on the part of the publisher, editors, the editorial board or their agents or employees is accepted for the consequences of any inaccurate or misleading information.

© Medinews (Cardiology) Ltd 2021. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers, Medinews (Cardiology) Ltd. It shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent.

All rights reserved. No part of this programme may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers, Medinews (Cardiology) Limited.

It shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent.

Medical knowledge is constantly changing. As new information becomes available, changes in treatment, procedures, equipment and the use of drugs becomes necessary. The editors/authors/contributors and the publishers have taken care to ensure that the information given in this text is accurate and up to date. Readers are strongly advised to confirm that the information, especially with regard to drug usage, complies with the latest legislation and standards of practice.

Healthcare professionals should consult up-to-date Prescribing Information and the full Summary of Product Characteristics available from the manufacturers before prescribing any product. Medinews (Cardiology) Limited cannot accept responsibility for any errors in prescribing which may occur.