The possible overuse of coronary angiography in the investigation of suspected coronary artery disease has been raised as a concern in the literature. We examined our own coronary angiography database to assess the diagnostic yield from angiography in the investigation of patients with suspected coronary artery disease and also the subsequent rate of referral for revascularisation. Some coronary artery disease was found in 66% of patients. However, in spite of an overall diagnostic yield in keeping with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines, only 28% of patients were referred for any form of revascularisation. The optimal use of coronary angiography has important resource implications and the rate of revascularisation may be a useful quality metric.

Introduction

For many years coronary angiography (CA) has been used as the gold standard in the assessment of coronary artery disease (CAD), and even a normal result is considered a worthwhile outcome.1 However, concern has been raised about the use and overuse of what is an invasive and expensive procedure.2-4 We examined our cardiac catheter database to assess our diagnostic yield in terms of detecting CAD, and also in terms of subsequent referral for coronary revascularisation, whether this be by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG), in a population of patients being assessed for possible CAD.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of cardiac catheter laboratory activity between 2007 and 2012 in a district general hospital with diagnostic-only catheter lab and four cardiologists. Patients investigated for valvular disease, or with any previous revascularisation, and non-elective patients were excluded.

angiography (CA) in 2,094 cases

The study population, therefore, consisted of all elective patients undergoing CA for the assessment of chest pain or other symptoms felt to be possibly due to CAD. All patients undergoing CA had the results of their investigation and management plan recorded on a database (Tomcat). The management plan would either involve referral for PCI or CABG, or to continue medical therapy. Coronary arteries were graded as being normal, having mild-to-moderate disease (no flow-limiting stenosis) or having single, double, triple or left main stem CAD.

Results

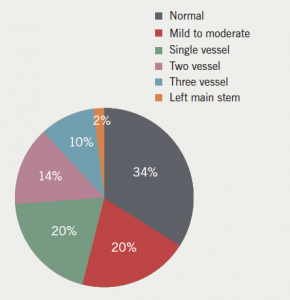

Of 2,094 cases, arteries were reported as normal in 710 (34%), having mild-to-moderate disease in 412 (20%), one-vessel disease in 414 (20%), two-vessel disease in 300 (14%), three-vessel disease in 214 (10%), and left main stem disease, with or without disease in other vessels, in 44 (2%) (figure 1).

The overall yield in terms of detecting CAD was 66% and the subsequent revascularisation rate was 17% for PCI and 11% for CABG, making a total revascularisation rate of 28% with a

PCI to CABG ratio of 1.6:1.

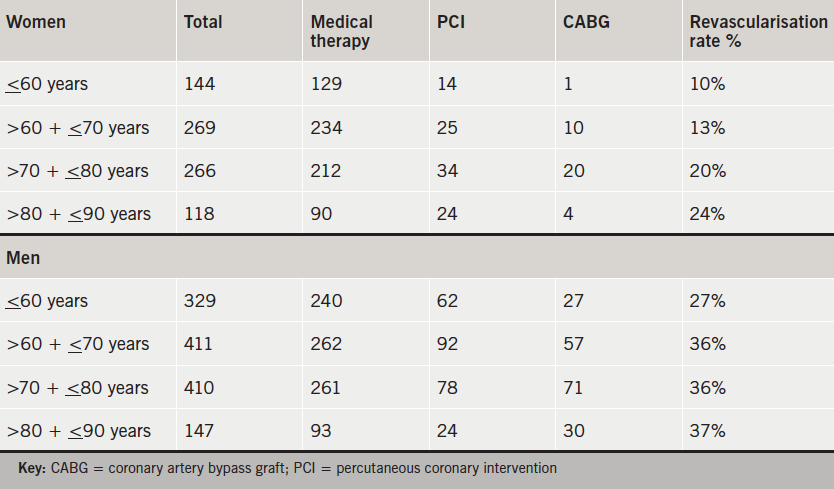

The breakdown of revascularisation rate by age and sex is shown in table 1.

Discussion

Although concerns have been raised about the overuse of CA, no consensus exists in terms of an acceptable diagnostic yield from the procedure in the elective setting.2-5 Similarly, no consensus exists as to an acceptable subsequent referral rate for revascularisation. UK registry data (British Cardiovascular Intervention Society) suggest an overall PCI to CA rate of 38%, but the data from centres used to derive this figure show a PCI to CA rate varying between less than 5% and greater than 120%. Such a degree of variation probably reflects the variation in types of unit, from small private hospitals to large tertiary referral centres, and does not distinguish between elective and non-elective patients (personal communication Peter Ludman).

Current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)6 guidelines for the investigation of new onset chest pain suggest that patients with a predicted likelihood of CAD of 61–90% should have a CA as their first investigation. In our population, the overall diagnostic yield in terms of detecting CAD was 66%, suggesting an overall use of angiography in keeping with current guidelines. However, the yield in terms of subsequent revascularisation was less than 30%. This was particularly low in women under 70 years old.

While NICE guidelines may provide a cost-effective pathway for diagnosing CAD, the relatively low rate of revascularisation suggests that we should examine the overall pathway in terms of both the diagnosis and management of CAD. There are few data describing the revascularisation yield following CA in patients with suspected CAD. Tandon et al.,7 using computed tomography (CT) angiography and myocardial perfusion imaging as a precursor to CA, had a revascularisation rate of approximately 60%. This is double the revascularisation rate observed in this study and suggests that using non-invasive techniques more could reduce the number of patients undergoing CA. Indeed, it may be that we should move away from using CA simply to assess the presence or absence of any possible CAD, and, instead, only perform CA in those patients who, on the basis of previous assessment, are highly likely to require revascularisation, so that patients might only need a single CA procedure.8

This observational study does have limitations. CA interpretation and subsequent treatment planning was not regularly performed as a part of a multi-disciplinary meeting. However, we would suggest that the practice was fairly typical for a district general hospital in the UK. The majority of CAs performed for the assessment of possible CAD do not result in referral for any form of coronary revascularisation. The proportion of normal coronaries found at angiography has been suggested as a possible quality metric,4,9 however, a more robust measure may also include the subsequent referral rate for revascularisation

Acknowledgements

With thanks to all the team in the cardiac catheter laboratory and to Dr Yuk Ki Wong. No funding was received for this research.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Key messages

- There is no consensus as to the optimal diagnostic yield from coronary angiography or the subsequent rate of referral for revascularisation

- Current thresholds for performing coronary angiography result in a sizeable proportion of coronary angiograms being normal or showing no significant disease

- The diagnostic yield from coronary angiography and rate of revascularisation could be a useful way of measuring the appropriateness of patient selection

References

1. Faxon DP, McCabe CH, Kregel DE, Ryan TJ. Therapeutic and economic value of a normal coronary angiogram. Am J Med 1982;73:500–05. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(82)90328-X

2. Douglas PS, Patel MR, Bailey SR et al. Hospital variability in the rate of finding obstructive coronary artery disease at elective diagnostic angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:801–09. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.05.019

3. Patel MR, Peterson ED, Dai D et al. Low diagnostic yield of elective coronary angiography. N Engl J Med 2010;362:148–50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0907272

4. Bradley SM, Maddox TH, Stanislawski MS et al. Normal coronary rates for elective angiography in the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System: insights from the VA CART Program. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:417–26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.055

5. Levitt K, Guo H, Wijeysundera HC et al. Predictors of normal coronary arteries at angiography. Am Heart J 2013;166:694–700. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2013.07.030

6. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE guideline CG95. Chest pain of recent onset: assessment and diagnosis of recent chest pain or discomfort of suspected cardiac origin. London: NICE, 2010. Available from: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG95

7. Tandon V, Hall D, Yam Y et al. Rates of downstream coronary angiography and revascularization: computed tomographic angiography vs. Tc-99m single photon emission computed tomography. Eur Heart J 2012;33:776–82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehr346

8. McKenzie DB, Turner NG, Khanna V, Rahmat R, Curzen N. Standby coronary angiography in elective patients with chest pain and the 18 week target; one solution to a national problem? Br J Cardiol 2008;15:312–15. Available from: https://bjcardio.co.uk/2008/11/standby-coronary-angiography-in-elective-patients-with-chest-pain-and-the-18-week-target-one-solution-to-a-national-problem/

9. Thomas MP, Gurm SH, Nallamothu BK. When is it right to be wrong? J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:427–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.010