Background

Heart failure is a clinical syndrome in which patients have typical symptoms (e.g. breathlessness, ankle-swelling and fatigue), and signs (e.g. elevated jugular venous pressure), due to an abnormality of cardiac structure or function.1 Its prevalence is high and increasing due an ageing population, improved survival rates following myocardial infarction, increased prevalence of risk factors such as diabetes and obesity – and better medical care. Patients with heart failure have a poor quality of life and reduced life expectancy. There are wide variations in the management of heart failure across the UK.2

Clinical definition

HeFREF/HeFNEF/HeFMREF

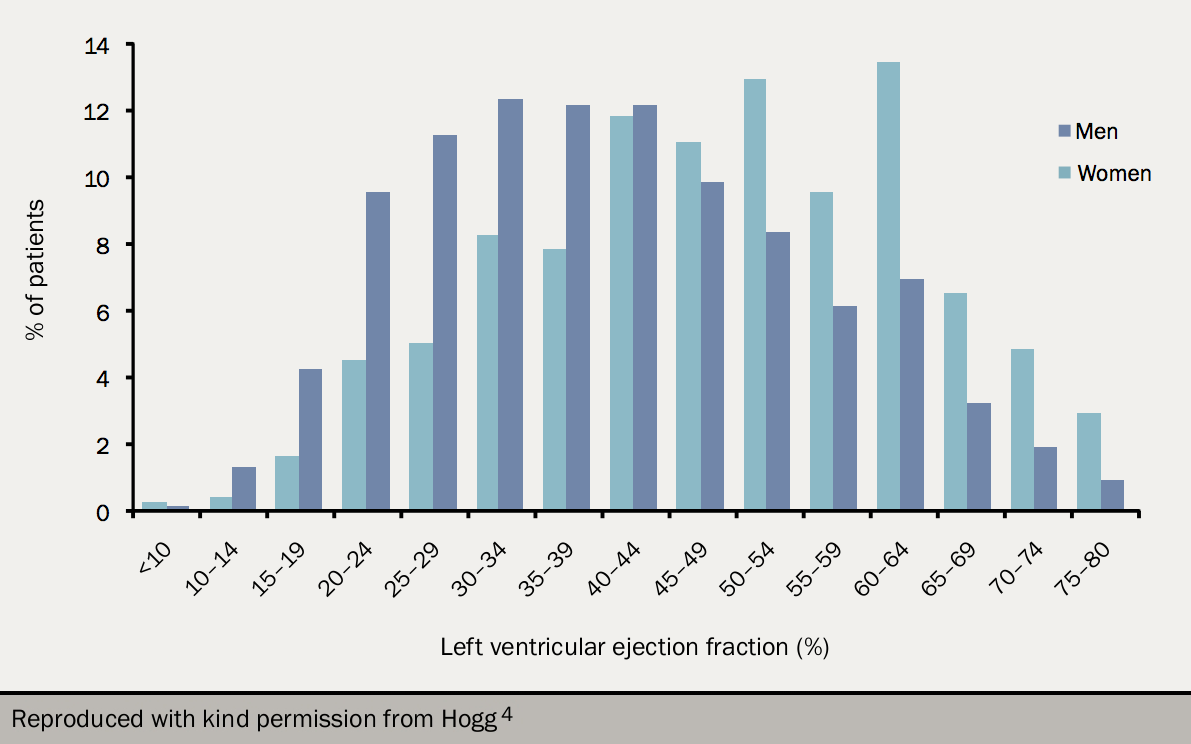

Patients with heart failure are often sub-divided in relation to their left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

- heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction (HeFREF) is due to impaired systolic, contractile function of the left ventricle – but it is important to realise that impaired systolic function does not happen in isolation. Patients with HeFREF invariably also have abnormal diastolic function

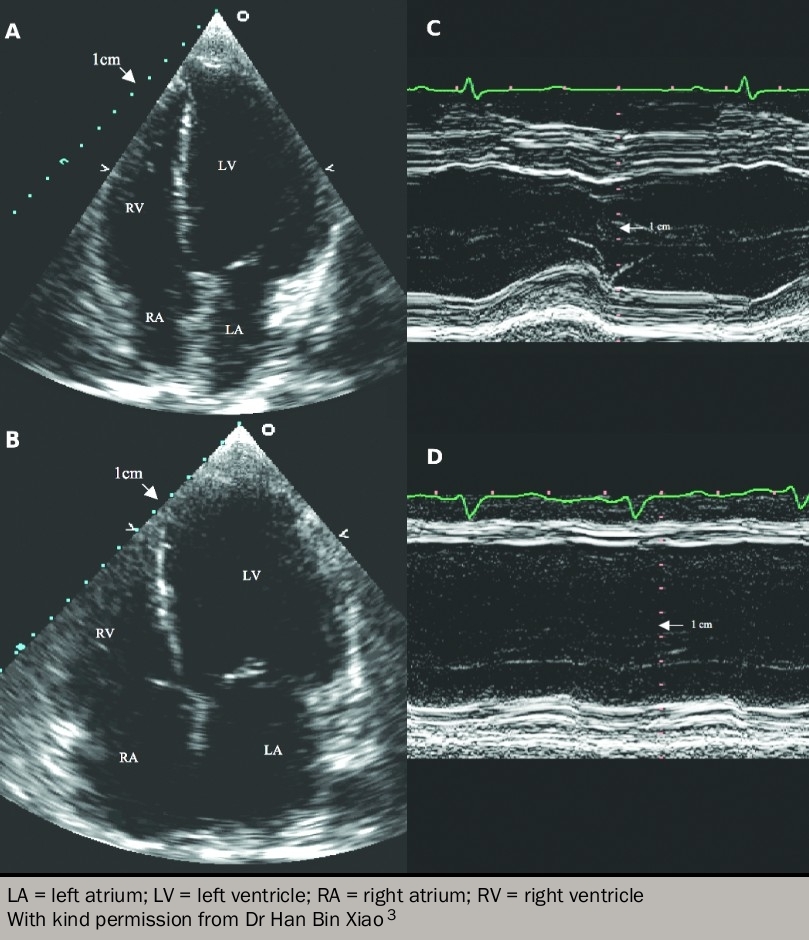

- some patients have signs and symptoms of heart failure but have a normal ejection fraction on echocardiography (figure 1). Such patients are variously labelled as having HeFNEF, HeFPEF (where the P stands for “preserved”) or “diastolic heart failure” (figure 2).

In some epidemiological studies, around half of all patients with heart failure have normal left ventricular systolic function.4,5 When compared to patients with reduced systolic function, those with preserved systolic function are:6,7

- more likely to be female

- older

- less likely to have coronary artery disease

- more likely to have hypertension

- more likely to have valvular heart disease

- more likely to have atrial fibrillation

- more likely to have diabetes or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- more likely to have muscle wasting (or sarcopaenia)

- often given different pharmacotherapy

- likely to have lower mortality rates.4

HeFNEF remains a controversial entity, and many believe that there is a significant risk of inappropriate diagnosis.

The definition of a ‘normal’ LVEF depends upon the method used to measure it and the population studied. Echocardiography is most widely used, but LVEF by echo is poorly reproducible: a patient said to have normal LVEF by one operator may, on a different day, or with a different operator, be said to have reduced ejection fraction.

A third heart failure phenotype has been proposed that lies in the ‘grey area’ between HeFREF and HeFNEF: heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction (HeFMREF) with LVEF 40-49%.1

The prevalence of HeFMREF is between 14-18% of patients with heart failure.8–11 Patients with HeFMREF are older and more likely to be female with greater burden of co-morbidities than patients with HeFREF, but with a similar prevalence of ischaemic heart disease (IHD).12

Thus patients with HeFMREF are similar to patients with HeFNEF. However, their prognosis is similar to that of HeFREF and their causes of death are closer to those seen in patients with HeFREF than HeFNEF.13,14

The clinical and laboratory characterstics of patients with HeFMREF are intermediate between HeFNEF and HeFREF.15 It is possible that those with HeFMREF are in transition from HeFNEF to HeFREF or vice versa.16–18 It is not at all clear as yet whether HeFMREF is a useful concept.

Despite much debate surrounding the value of LVEF as a measure of cardiac function, there is no doubt that it is helpful in defining patients who are likely to respond to specific therapies. Clinical trials have unequivocally demonstrated the benefit of modern medical therapy for patients with heart failure – but only amongst those with HeFREF, however that reduced ejection fraction is defined.

There are other curiosities surrounding LVEF, too: although much quoted epidemiological studies suggest that patients with HeFNEF have much the same prognosis as those with HeFREF,19 every trial population in whom LVEF has been measured reports a linear relation between increasing LVEF and increasing survival.

Acute heart failure versus chronic heart failure

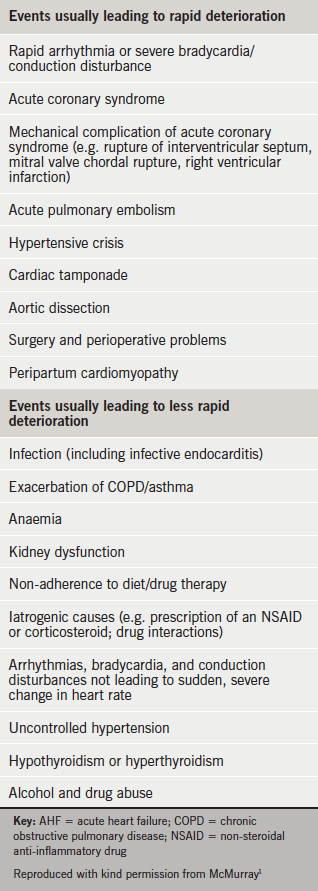

Acute heart failure is the rapid onset of, or worsening of the symptoms and signs of heart failure (table 1). It includes patients with sudden-onset dyspnoea due to acute pulmonary oedema but also those admitted to hospital with fluid retention without breathlessness at rest. Patients are often thought to lie along a spectrum with acute pulmonary oedema at one end, and gross fluid retention at the other: however, acute pulmonary oedema is mostly an acute dramatic event precipitated by a discrete event such as acute ischaemia or an arrhythmia. An appropriate working definition is that acute heart failure is heart failure that leads to a patient seeking urgent medical attention and often results in hospitalisation.

The pathophysiology of acute heart failure can usually be understood in terms of abnormal haemodynamics, but the pathophysiology of chronic heart failure, especially when treated, is more complex (see next page).

All rights reserved. No part of this programme may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers, Medinews (Cardiology) Limited.

It shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent.

Medical knowledge is constantly changing. As new information becomes available, changes in treatment, procedures, equipment and the use of drugs becomes necessary. The editors/authors/contributors and the publishers have taken care to ensure that the information given in this text is accurate and up to date. Readers are strongly advised to confirm that the information, especially with regard to drug usage, complies with the latest legislation and standards of practice.

Healthcare professionals should consult up-to-date Prescribing Information and the full Summary of Product Characteristics available from the manufacturers before prescribing any product. Medinews (Cardiology) Limited cannot accept responsibility for any errors in prescribing which may occur.