Interruption of anticoagulation in valve patients

Interruption of anticoagulation carries a risk of thrombosis, and for procedures with a low risk for bleeding, such as dental extraction, simple skin biopsy, cataract surgery and endoscopy without biopsy or with mucosal biopsy only, anticoagulation should not be stopped. The INR should be checked on the day of the procedure and must be no higher than the therapeutic range.

Some procedures such as pacemaker implantation and cardiac ablation may be safer performed without cessation of anticoagulation or bridging, but with facilities to give prothrombin complex concentrate to reverse the anticoagulation if severe bleeding occurs. It is reasonable to reduce the INR to no more than 3.0 in these circumstances.

For major procedures where the risk of bleeding is greater, VKA should be stopped 4–5 days prior to the procedure. For patients with low risk prosthetic valves (aortic position) and no patient risk factors for thrombosis it is not necessary to provide bridging therapy but, for other mechanical valves or for patients with thrombotic risk factors, bridging with heparin or LMWH is recommended once the INR falls below therapeutic range.

Options for bridging therapy include:

- Intravenous UFH to achieve therapeutic levels as above, stopping 2–4 hours prior to the surgery.

- LMWH (unlicensed use) in therapeutic weight-related doses once or twice daily (e.g. enoxaparin 1.5 mg/kg once daily or 1 mg/kg twice daily), with the last dose given at least 24 hours prior to surgery.

- Caution should be used to ensure haemostasis is secure before restarting heparin or LMWH in therapeutic doses after major surgery, especially in the first 24–48 hours, when lower prophylactic doses should be considered instead.

- For patients requiring mandatory intensive anticoagulation to protect heart valves, neuraxial anaesthaesia or analgaesia should be avoided if possible, or used with great caution and with attention to the coordination of the timing of insertion and removal of the catheter and anticoagulant dosing.

- VKA may be restarted once haemostasis is secure with no loading dose or a small increase on normal dose on the first day only. Heparin or LMWH should continue until the INR is therapeutic.

- The practicalities of bridging therapy must be resolved between the interventional team and the anticoagulant service, so that the patient understands what is to happen and receives the intended treatment. Not all GP practices are able to prescribe therapeutic doses of LMWH.

Pregnancy management

Bioprosthetic heart valve

Pregnancy is generally well managed in pregnant women with a bioprosthetic heart valve. The risk is low in woman with minimal bio-prosthesis dysfunction and normal ventricular function.2

Mechanical heart valve:

Anticoagulation is essential in pregnant women with mechanical heart valves with historical observational studies showing that one in four woman with mechanical prosthesis experienced a thromboembolic event during pregnancy.3

Women of childbearing age should be informed of the risks before cardiac surgery and the commencement of anticoagulation.

VKA crosses the placenta. Between 6–13 week gestation, VKA usage is associated with foetal embryopathy, which includes facial, brain and limb abnormalities. There is also an increased risk of foetal loss and foetal haemorrhage later on in the pregnancy. VKA, however, offers the most effective prevention against thromboembolic events for the mother.

Heparin does not cross the placenta and is therefore safe for the foetus. However the use of subcutaneous (SC) UFH throughout pregnancy has been associated with an unacceptable high incidence of valve thrombosis of up to 33%.3 High-intensity LWMH with adjusted anti-Xa monitoring has been used successfully in pregnant woman with mechanical heart valves.4 Nevertheless, many studies have reported high incidences of valve thrombosis despite meticulous monitoring of peak anti-Xa levels.5,6

The use of NOACs is not recommended in all pregnant women.

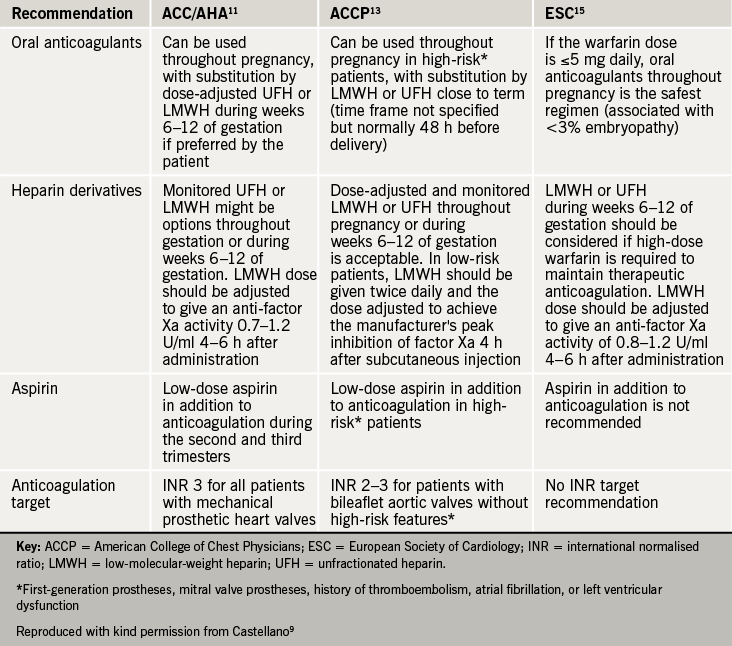

The American College of Clinical Pharmacology and the European Society of Cardiology have published recommendations (see table 2)9 on the management of anticoagulation in pregnant woman with mechanical heart valves but the decisions about management are highly dependent on the woman’s choice, and must be made by experienced clinicians with her full involvement. A multi-disciplinary obstetric/ haematology/ cardiology team must be involved in the management all pregnant women with mechanical heart valves.

Options for anticoagulation:

- Adjusted dose LMWH twice daily throughout pregnancy (unlicensed use), to achieve peak therapeutic levels of anti-Xa activity four hours after injection, with frequent monitoring and dose adjustment as required

- LMWH or UFH until 13 weeks gestation, with VKA from then until shortly before delivery when LMWH or UFH can be resumed

- For women at highest risk of thromboembolism, such as those with older mitral prostheses, AF or a history of thromboembolism, VKA may be advisable throughout pregnancy with substitution by LMWH or UFH shortly before delivery

- Low-dose aspirin may be a useful addition for women at particularly high risk.