Complications

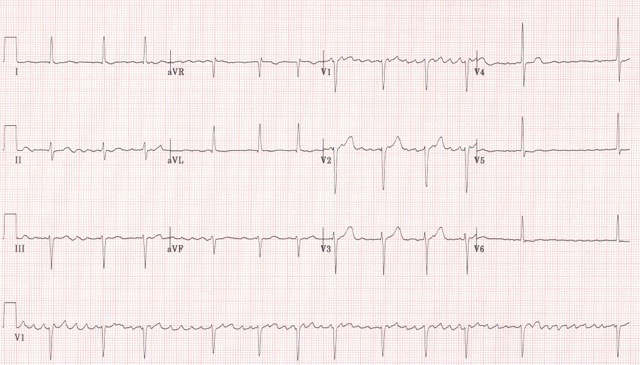

Arrhythmias are common complications of heart failure, especially atrial fibrillation (AF) (figure 14) which can increase the risk of stroke and thromboembolism or ventricular arrhythmias.1

Atrial fibrillation

If patients with heart failure develop AF (figure 14) either permanent or paroxysmal, should be assessed for potentially reversible causes and stroke risk. Unless there is a very strong contra-indication, patients with heart failure and AF should be anticoagulated.

Potential reversible causes of AF in heart failure

- hyperthyroidism

- electrolyte disorders

- uncontrolled hypertension

- mitral valve disease.

Potential precipitating factors of AF in heart failure

- recent surgery

- chest infection or exacerbation of COPD/asthma

- acute myocardial ischaemia

- alcohol binge.

Ventricular arrhythmias

Episodes of asymptomatic, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia are common. “Complex ventricular arrhythmias”, include frequent premature ventricular complexes and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia are associated with a poor outcome.1

Co-morbidities

Patients with heart failure have a wide range of co-morbidities due to their advanced age. Some co-morbidities will cause heart failure in the first place, for example, cancer treatment with chemotherapy. Others are risk factors for developing heart failure, such as obesity or hypertension (see below). Polypharmacy is a common consequence and can be very challenging.

Co-morbidities of heart failure include:

• Depression

View details

• Anaemia

View details

• Diabetes

View details

• COPD

View details

• Hyperuricaemia and gout

View details

• Hypertension

View details

• Obesity

View details

• Sleep disturbances

View details

Conclusion

Heart failure has a profound impact on quality of life, prognosis and survival of those affected. Its incidence and prevalence rise with age due to better healthcare and therapeutic advances. It is a costly condition to diagnose and manage, representing 1–2% of total NHS expenditure and an annual cost of care of £625 million, mainly due to the high rates of readmission, high volume of consultations and prescriptions.

Survival rates for acute heart failure vary post discharge depending on age at admission, presence or absence of LVSD, place of care (cardiology ward or general medical ward), therapeutic options (whether ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta blockers and diuretics have been initiated according to guidelines) and on referral follow up with a cardiology specialist.

The pathophysiology of heart failure remains key to understanding how to diagnose and manage the different types of heart failure accordingly.

In following modules, we will explore investigations, diagnosis algorithm and pharmacological and non-pharmacological options for the management of heart failure.

close window and return to take test

References

1. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 18:891–975 http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.592

2. Donkor A, McDonagh T, Hardman S et al. The National Heart Failure Audit April 2015 – March 2016 (2016). Available from: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/nicor/audits/heartfailure/documents/annualreports/annual-report-2015-6-v8.pdf [Accessed 15 August 2017]

3. Xiao HB. Echocardiography in primary care. In McIntyre H (Ed). Heart failure in older patients. London: Concise Clinical Consulting, 2007

4. Hogg K, Swedberg K, McMurray J. Heart failure with preserved left ventricular systolic function; epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 43:317–27 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.046

5. McDonagh TA, Gardner RS, Clark AL, Dargie H (ed.). Oxford Textbook of Heart Failure. Oxford: Oxford University Press, July 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/med/9780199577729.001.0001

6. Pellicori P, Cleland JG. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Clin Med (Lond) 2014; 14 Suppl 6:s22–8 https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.14-6-s22

7. Ferrari R, Böhm M, Cleland JGF, Paulus WJS, Pieske B, Rapezzi C, Tavazzi L. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: uncertainties and dilemmas. Eur J Heart Fail 2015; 17:665–71 https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.304

8. Solomon SD, Anavekar N, Skali H et al. Influence of ejection fraction on cardiovascular outcomes in a broad spectrum of heart failure patients. Circulation 2005; 112:3738–44 https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.561423

9. Fonarow GC, Stough WG, Abraham WT et al. Characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with preserved systolic function hospitalized for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50:768–77 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.064

10. He KL, Burkhoff D, Leng WX et al. Comparison of left ventricular structure and function in Chinese patients with heart failure and ejection fractions >55% versus 40 to 55% versus <40%. Am J Cardiol 2009; 103:845–51 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.11.050

11. Steinberg BA, Zhao X, Heidenreich PA et al. Trends in patients hospitalized with heart failure and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Prevalence, outcome and therapies. Circulation 2012; 126:65–75 https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.080770

12. Kapoor JR, Kapoor R, Ju C, et al. Precipitating clinical factors, heart failure characterization, and outcomes in patients hospitalized with heart failure with reduced, borderline, and preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol HF 2016; 4:464–72 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2016.02.017

13. Gottdiener JS, McClelland RL, Marshall R et al. Outcome of congestive heart failure in elderly persons: influence of left ventricular systolic function. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Intern Med 2002; 137:631–9 https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-137-8-200210150-00006

14. Pascual-Figal DA, Ferrero-Gregori A, Gomez-Otero I et al. Mid-range left ventricular ejection fraction: Clinical profile and cause of death in ambulatory patients with chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2017; pii: S0167-5273(17)30596-X. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.03.032 [Epub ahead of print]

15. Rickenbacher P, Kaufmann BA, Maeder MT et al. Heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction: a distinct clinical entity? Insights from the Trial of Intensified versus standard Medical therapy in Elderly patients with Congestive Heart Failure (TIME-CHF). Eur J Heart Fail 2017 https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.798 [Epub ahead of print]

16. Hwang SJ, Melenovsky V, Borlaug BA. Implications of coronary artery disease in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63(25 Pt A):2817–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.034 [Epub 2014 Apr 23]

17. Clarke CL, Grunwald GK, Allen LA et al. Natural history of left ventricular ejection fraction in patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013; 6:680–6 https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000045

18. Lam CS, Teng TH. Understanding Heart Failure With Mid-Range Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail 2016; 4(6):473–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2016.03.025

19. Bhatia RS, Tu JV, Lee DS, Austin PC, Fang J, Haouzi A, Gong Y, Liu PP. Outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in a population-based study. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:260–9 https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa051530

20. The Office for National Statistics. Deaths. London: United Kingdom Government, 2015. Available from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/datasets/deathsregisteredinenglandandwalesseriesdrreferencetables [accessed 10th May 2017]

21. Sutherland K. Bridging the quality gap: heart failure. The Health Foundation. March 2010. Available from http://www.health.org.uk/publications/bridging-the-quality-gap-heart-failure/ [Accessed 10th May 2017]

22. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence CG108. Chronic heart failure: management of chronic heart failure in adults in primary and secondary care. London: NICE, 2010. Available from www.nice.org.uk/cg108 [Accessed 10th May 2017]

23. Townsend N, Wickramasinghe K, Bhatnagar P, et al. Coronary heart disease statistics 2012 edition. British Heart Foundation: London 2012. Available from http://www.bhf.org.uk/publications/view-publication.aspx?ps=1002097

24. NHS Digital. Quality and outcomes framework (QOF) – 2014–15. Available from: http://content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB18887 [accessed 10th May 2017]

25. Mamas MA, Sperrin M, Watson MC, et al. Do patients have worse outcomes in heart failure than in cancer? A primary care-based cohort study with 10-year follow-up in Scotland. Eur J Heart Fail 2017 https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.822 [Epub ahead of print]

26. UK Government. Summary of QoF Indicators. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/213226/Summary-of-QOF-indicators.pdf[accessed 10th May 2017]

27. NHS England. Letter to service re: GP contract 2017–18. Available from https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/gp-contract-17-18-letter-to-service.pdf [accessed 10th May 2017]

28. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence QS103. Acute heart failure quality in adults. London: NICE, 2016. Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs103/chapter/List-of-quality-statements [Accessed 10th May 2017]

29. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence QS103. Chronic heart failure in adults. London: NICE, 2016. Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs9/chapter/List-of-quality-statements [Accessed 10th May 2017]

30. Department of Health. Payment by results guidance for 2010–11. Leeds: Payment by Results team, Department of Health, 2010 http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130105041537/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/@ps/documents/digitalasset/dh_112970.pdf

31. NHS England. 2017/18 and 2018/19 National Tariff Payment System:

a consultation notice Annex B6: Guidance on best practice tariffs

https://improvement.nhs.uk/uploads/documents/Annex_B6_-_guidance_on_BPTs.pdf [accessed 10th May 2017]

32. Ather S, Chan W, Bozkurt B et al. Impact of noncardiac comorbidities on morbidity and mortality in a predominantly male population with heart failure and preserved versus reduced

ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 59:998–1005 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.040

33. ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA 2002; 288(23):2981–97 https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.23.2981

Further recommended reading

Henderson J. A Life of Ernest Starling. Oxford University Press, 2010

close window and return to take test

All rights reserved. No part of this programme may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers, Medinews (Cardiology) Limited.

It shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent.

Medical knowledge is constantly changing. As new information becomes available, changes in treatment, procedures, equipment and the use of drugs becomes necessary. The editors/authors/contributors and the publishers have taken care to ensure that the information given in this text is accurate and up to date. Readers are strongly advised to confirm that the information, especially with regard to drug usage, complies with the latest legislation and standards of practice.

Healthcare professionals should consult up-to-date Prescribing Information and the full Summary of Product Characteristics available from the manufacturers before prescribing any product. Medinews (Cardiology) Limited cannot accept responsibility for any errors in prescribing which may occur.

All rights reserved. No part of this programme may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers, Medinews (Cardiology) Limited.

It shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent.

Medical knowledge is constantly changing. As new information becomes available, changes in treatment, procedures, equipment and the use of drugs becomes necessary. The editors/authors/contributors and the publishers have taken care to ensure that the information given in this text is accurate and up to date. Readers are strongly advised to confirm that the information, especially with regard to drug usage, complies with the latest legislation and standards of practice.

Healthcare professionals should consult up-to-date Prescribing Information and the full Summary of Product Characteristics available from the manufacturers before prescribing any product. Medinews (Cardiology) Limited cannot accept responsibility for any errors in prescribing which may occur.