Pacemakers are being implanted with increasing frequency. As with every procedure, there is the potential for complications. There are little recent data on implant complications and consequently we may be misinforming patients when we consent them.

Data from all pacing procedures performed from February 2007 to January 2010 were analysed retrospectively. All chest X-rays and their reports were inspected for pneumothoraces and lead displacements. Correspondence to our local pacemaker extraction centre was used to identify patients with pacemaker infections requiring extraction. Discharge summaries were also used to identify patients with other complications that were not discovered by the above methods.

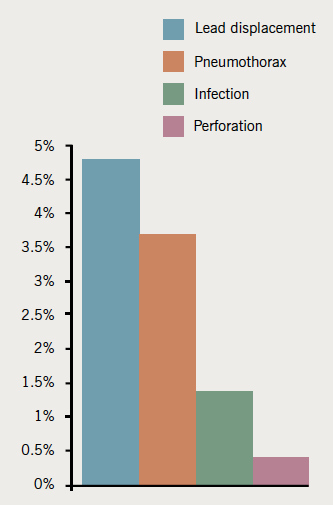

A total of 1,286 procedures took place over the three-year period. There were a total of 94 (7.5%) complications. Lead displacement was the most common complication occurring in 39 (4.8%) procedures requiring leads. Pneumothorax occurred in 30 (3.7%) patients. Infection occurred in 19 (1.5%) patients. Perforation occurred in three (0.37%) patients.

These are unselected data from a high volume district general hospital (DGH). Infection rates are low. Lead displacement rates are higher than other similar studies. Pneumothorax rates are also high, reflecting the fact that almost all access is via the subclavian vein.

Introduction

Pacemakers are frequently implanted and the rate of implantation is increasing. For pacemaker and implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) implants the 10-year average growth rate is 4.7% and 15.1%, respectively.1 Total cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT) implant rates also rose significantly in England and Wales in 2009.1

Pacemakers are frequently implanted and the rate of implantation is increasing. For pacemaker and implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) implants the 10-year average growth rate is 4.7% and 15.1%, respectively.1 Total cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT) implant rates also rose significantly in England and Wales in 2009.1

As with every procedure, there is potential for complications. Unfortunately, there are little data on implant complications outside of major trials and, as such, we may be misinforming patients when we consent them.

Complications of pacemaker implantation are related to venous access (pneumothorax, haemothorax, damage to subclavian artery), leads (perforation, lead displacement, infection, venous thrombosis), and the generator (infection, erosion, haematoma). Death may rarely occur with an incidence of 0.08–0.1% and 0.9–1.1% in simple pacing and complex pacing, respectively.2-4

This study was undertaken to assess the acute complication rate of pacing procedures related to the implant itself in a large district general hospital and compare this with other studies published in the literature.

Methods

Data from all simple (single chamber – ventricular pacemaker [VVI], dual-chamber pacemaker [DDD], implantable loop recorders, generator box changes) and complex pacing (ICD, cardiac resynchronisation therapy with pacing [CRT-P], cardiac resynchronisation therapy with defibrillator [CRT-D], bi-atrial, generator box changes) from February 2007 to January 2010 at our hospital, were analysed retrospectively. All chest X-rays and their reports were inspected for pneumothoraces and lead displacements. Aside from inspecting the procedure logs to identify pacemakers extracted locally, correspondence to our local tertiary referral centre was used to identify patients with pacemaker infections requiring extraction within the three-year period. Discharge summaries were also used to identify patients with other complications that were not discovered by the above methods.

There were 16 different operators over the three-year period, all with differing levels of experience ranging from first year registrar to consultant. All complex pacing was performed by consultants. Venous access was almost always achieved via the subclavian vein. Intravenous antibiotics (1 g flucloxacillin, 600 mg clindamycin if penicillin allergic, and 3 mg/kg gentamicin) were given prior to the procedure and 48 hours of oral antibiotics (500 mg flucloxacillin four times daily or 300 mg clindamycin four times daily if penicillin allergic) following the procedure. During this period warfarin was stopped peri-procedure and bridged with heparin if a mechanical valve was in situ.

Results

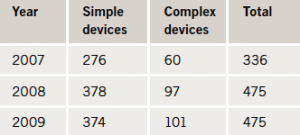

A total of 1,286 procedures took place over the three-year period (table 1). There was an approximately equal gender split for simple pacing procedures (male:female 55%:45%). However, for complex pacing, the majority of procedures were performed on males (male:female 81%:19%). The mean age at implant for simple pacing was 77.1 (range 17.3–99.7) years. For complex pacing the mean age was 66.7 (range 27.0–85.9) years.

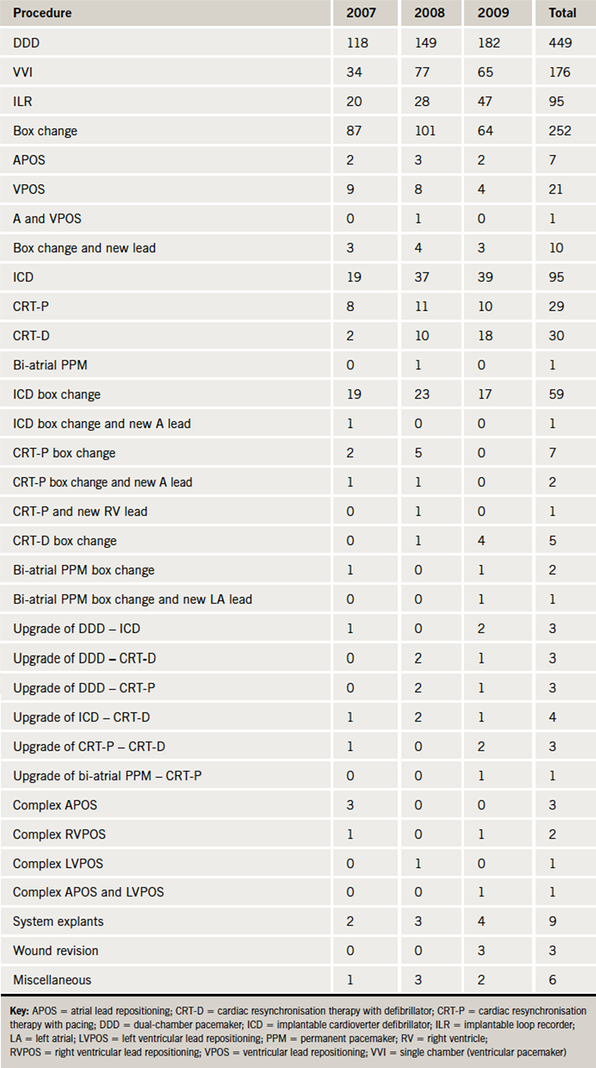

The type of pacing procedure performed is described in table 2 and figure 1.

Complications

There were a total of 96 (7.5%) complications (figure 2): 71 (6.9%) occurred in simple pacing and 25 (9.7%) occurred in complex pacing.

Lead displacement was the most common complication occurring in 39 (4.8%) procedures requiring leads. Overall, 13/589 (2.2%) right atrial (RA) leads displaced, 24/799 (3%) right ventricle (RV) leads displaced and 2/68 (2.9%) left ventricle (LV) leads displaced. Lead displacement was more common in simple pacing compared with complex pacing (5.2% vs. 3.4%). In simple pacing, the occurrence of ventricular lead displacement was higher than for the atrial leads (3.6% vs. 2.2%). In complex pacing, atrial leads were displaced more commonly than RV leads (2.2% vs. 0.6%). The lead displacement rate for all implants improved over the three-year period

(2007 – 8.5%, 2008 – 5.4%, 2009 – 2.1%).

Pneumothorax occurred in 30 (3.7%) patients requiring venous access. Of these 17 (56.7%) were managed conservatively, 9 (30%) were managed with aspiration and four (13.3%) had an intercostal chest drain inserted. Therefore, 1.5% of patients required a further procedure as a result of a pneumothorax. A pneumothorax was more common in simple pacing compared with complex pacing: 28 (4.4%) and two (1.1%) cases, respectively. Pneumothorax was more common in dual-chamber pacing compared to single-chamber pacing (4.2% vs. 2.3%).

Infection occurred in 19 (1.5%) patients. Infections mostly presented one to six months after implant. Infection was more common in complex pacing compared with simple pacing procedures (3.9% vs. 0.9%). Infected devices were removed, but two wound infections were managed successfully with intravenous antibiotics. Thirteen devices were explanted and four were referred for extraction at our local tertiary referral centre. In this series, most infections occurred after new implants (14/19 cases). Two infections occurred after box changes, two following wound revisions for erosion and one after re-operation for lead displacement. Erosion occurred in one simple pacing procedure but the device had been implanted in 2005. The wound revision took place in 2009, but unfortunately the device became infected and was ultimately extracted. Erosion also occurred in two complex pacing procedures. One of these devices was extracted and the other had a new pocket created, which later became infected and the device was explanted. Haematoma requiring intervention occurred in two complex pacing patients. Perforation occurred in three (0.37%) patients requiring leads; one of these required pericardiocentesis. There was one retained guide wire in this series, which was removed by an interventional radiologist.

Discussion

These are unselected data from a high volume district general hospital (DGH). A total of 1,286 procedures took place over a three-year period with a 7.5% complication rate. Complications were more common in complex pacing compared with simple pacing. The most common complication was lead displacement (4.8%) followed by pneumothorax (3.7%). Infection occurred in 1.5% of cases. Perforation was rare (0.37%).

Other studies have revealed similar results to our series but our rates of lead displacement and pneumothorax are higher. In the Pacemaker Selection in the Elderly (PASE) study, 6.1% of the 407 patients receiving dual-chamber pacing systems had a complication of implantation. There were nine (2.2%) lead displacements, eight (2%) pneumothoraces and four (1%) cardiac perforations.2

Aggarwal et al. enrolled 1,088 patients and found a lead displacement rate of 1.4% (atrial lead displacement 1.6% and ventricular lead displacement 0.5%). Pneumothorax occurred in 1.9% of subclavian vein punctures. Infection occurred in 1.7% of patients (0.9% required re-operation, whereas 0.8% were treated successfully with a single course of antibiotics).5

In a single-centre study of over 1,300 pacemaker implantations reported by Tobin et al., complications occurred in 4.2% of patients. Lead displacement occurred in 2.4%, ‘significant’ pneumothorax in 1.5%, pericardial tamponade in 0.2% and haemothorax leading to death in one patient (0.08%).3

The incidence of complications in ICD and CRT-D implants was investigated by Reynolds and colleagues among Medicare beneficiaries. The incidence of pneumothorax was 1% and 1.2%, respectively. Incidence of infection was 1.4% and 0.7%. Lead or pocket revision occurred in 1.2% and 1.8% of patients. Pericardial effusion/tamponade occurred in 0.3% of cases in both groups. Death occurred in 0.9% and 1.1%.4

Grimm and colleagues investigated complications in ICD implants in 241 patients and found an incidence of infection of 5% and lead displacement of 4%.6

In our series, of both simple and complex device implants, lead displacement occurred most frequently, which is consistent with other similar studies; however, our displacement rate with regards to simple devices was higher. The displacement rate for complex pacing was lower than for simple pacing, perhaps reflecting the use of active fixation leads and operator experience. However, the right ventricular defibrillator leads used for complex pacing are stiffer and, if a screw-in helix is used, the risk of perforation is generally accepted to be higher, particularly, perhaps, for those leads with a smaller diameter.7,8

The displacement rate for all implants improved over the three-year period, which may reflect increased experience and improved training. The results for complex pacing are skewed by data from 2007 where there was a 12.1% incidence of lead displacement; four leads displaced in 33 cases. For 2008 and 2009 there was a 1% incidence of lead displacement. Of concern, and not in keeping with other studies, was that our ventricular lead displacement rate in simple pacing was higher than atrial lead displacement rates. It is unclear as to why this is, but could be due to operator technique or aftercare/education of the patient.

The favoured method of venous access at our hospital is via the subclavian approach. This is known to be associated with a risk of pneumothorax. Pneumothorax rates in the literature vary from 0.7% to 5.2% with an average of approximately 2%.2-5,9-12 Our rate of pneumothorax in simple pacing procedures requiring leads was 4.4%. Pneumothorax rates in complex pacing were lower (1.1%) reflecting the experience of the operators who were all at consultant grade. Pneumothorax was more common in dual-chamber pacing compared with single-chamber pacing (4.2% vs. 2.3%) and is most likely due to a second subclavian puncture being performed to facilitate the passage of two leads. Altogether, 1.5% of patients required a further procedure as a result of the pneumothorax, which increases the length of stay, costs to the trust4 and X-ray exposure. The risk of pneumothorax is virtually eliminated by using the cephalic vein for access, but this route is not necessarily suitable for all procedures.

Infection of the pacemaker pocket or leads occurred in 1.5% of cases, which is similar to other studies. Infection, haematoma and erosion were more common in complex pacing and may reflect the size of device used and that the patients tend to have more comorbidities. It is important to create an adequately sized pocket without tension around the device or at wound closure. The pocket should be inspected prior to implantation of the device to ensure that all bleeding points have stopped. Recently, a surgical skills course for implantation of cardiac rhythm devices has been developed and addresses these issues as well as aseptic technique and suture selection.13

Overall complication rates were higher in complex pacing due to a higher infection, erosion and haematoma rate. Haematoma may have occurred more frequently as warfarin was stopped for the procedure and bridged with heparin if a mechanical valve was in situ. However, due to recent studies, this is no longer practiced at our centre and warfarin is now continued for the procedure.14

Lead displacements and pneumothorax rates were much lower in complex pacing than for simple pacing. All of the complex implants were performed by a consultant and this increased experience is associated with a lower complication rate.2,15,16

During the period of follow-up in this series, all lead displacements that required re-operation, were discovered within three months of implantation and all system infections were detected within six months. It is known, however, that late complications can occur years after implant, but are rare.15,17,18 These late complications may not be detected in a series such as this.

Limitations of the study

The main limitation to our series is its retrospective nature. These are also data from a single centre and may not reflect experiences in other centres. Cases of infection and lead displacement could have been missed for 2009 as lead displacements presented up to three months later and cases of infection six months later. In other cases, patients may have had their pacemakers downgraded to avoid lead repositioning and so the actual displacement rate may have been higher. These patients with suboptimal parameters may present several years later requiring re-operation and will, therefore, be under-reported in studies such as this. These are hard to quantify using existing databases, and additional fields on the central cardiac audit database (CCAD) may help with this. Haematoma rates are also difficult to quantify as assessment of a significant haematoma is subjective and individual operators vary in their approach to managing this condition.

Conclusion

Pacemaker implantation is increasing in frequency and new indications are being developed regularly. The morbidity associated with these procedures is not insignificant and the patient should be consented for this prior to implant. With increasing operator experience these complications are reduced. It is difficult to know how these results compare with similar centres and what is required is a robust method for collecting data prospectively on all implants using well-defined criteria for complications. The addition of fields relating to complications to CCAD would be the most logical way of achieving this.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Key messages

- Pacemakers are being implanted with increasing frequency

- Lead displacement was the most common complication occurring in 4.8% of procedures. Pneumothorax

occurred in 3.7% of patients. Infection occurred in 1.5% of patients - Complications were more common in complex pacing

- A robust method for collecting data prospectively on all implants using well-defined criteria for complications is required, and we would suggest expanding the fields in the central cardiac audit database (CCAD)

References

- Heart rhythm devices: UK National Clinical Audit 2009. Available from: http://www.ccad.org.uk/device.nsf

- Link MS, Estes NAM III, Griffin JJ et al. Complications of dual chamber pacemaker implantation in the elderly. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 1998;2:175–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1009707700412

- Tobin K, Stewart J, Westveer D, Frumin H. Acute complications of permanent pacemaker implantation: their financial implications and relation to volume and operator experience. Am J Cardiol 2000;85:774–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9149(99)00861-9

- Reynolds MR, Cohen DJ, Kugelmass AD et al. The frequency and incremental cost of major complications among Medicare beneficiaries receiving implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:2493–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2006.02.049

- Aggarwal RK, Connelly DT, Ray SG et al. Early complications of permanent pacemaker implantation: no difference between dual and single chamber systems. Br Heart J 1995;73:571–5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/hrt.73.6.571

- Grimm W, Flores B, Marchlinski F. Complications of implantable cardiovertor defibrillator therapy: follow-up of 241 patients. PACE 2006;16:218–22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.1993.tb01565.x

- Sterlinski M, Przybylski A, Maciag A et al. Subacute cardiac perforations associated with active fixation leads. Europace 2009:11;206–12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/europace/eun363

- Implantable Pacing Leads and Risk of Cardiac Perforation – Boston Scientific product update. Available from: http://www.bostonscientific.com/templatedata/imports/HTML/CRM/Product_

Performance_Resource_Center/news/pdf/Implantable_Pacing_Leads_and_Risk.pdf - Kiviniemi MS, Pimes MA, Eranen HJ, Kettunen RV, Hartikainen JE. Complications related to permanent pacemaker therapy. PACE 1999;22:711–20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.1999.tb00534.x

- Magney JE, Parsons JA, Flynn DM, Hunter DW. Pacemaker and defibrillator lead entrapment: case studies. PACE 1995;18:1509–17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.1995.tb06737.x

- Parsonnet V, Roelke M. The cephalic vein cutdown versus subclavian puncture for pacemaker/ICD lead implantation. PACE 1999;22:695–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.1999.tb00531.x

- Calkins H, Ramza BM, Brinker J et al. Prospective randomized comparison of the safety and effectiveness of placement of endocardial pacemaker and defibrillator leads using the extrathoracic subclavian vein guided by contrast venography versus the cephalic approach. PACE 2001;24:456–64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1460-9592.2001.00456.x

- Essential surgical skills for cardiologists – Royal College of Surgeons of England. Available from: http://www.rcseng.ac.uk/education/courses/essential-surgical-skills-for-cardiologists

- Ghanbari H, Feldman D, Schmidt M et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy device implantation in patients with therapeutic international normalized ratios. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2010;33:400–06. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.02703.x

- Eberhardt F, Bode F, Bonnemeier H et al. Long term complications in single and dual chamber pacing are influenced by surgical experience and patient morbidity. Heart 2005;91:500–06. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2003.025411

- Parsonnet V, Bernstein AD, Lindsay B. Pacemaker-implantation complication rates: an analysis of some contributing factors. J Am Coll Cardiol 1989;13:917–21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0735-1097(89)90236-2

- Harcombe A, Newell S, Ludman P et al. Late complications following permanent pacemaker implantation or elective unit replacement. Heart 1998;80:240–4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/hrt.80.3.240

- Johansen J, Jorgensen O, Moller M et al. Infection after pacemaker implantation: infection rates and risk factors associated with infection in a population-based cohort study of 46299 consecutive patients. Eur Heart J 2011;32:991–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehq497